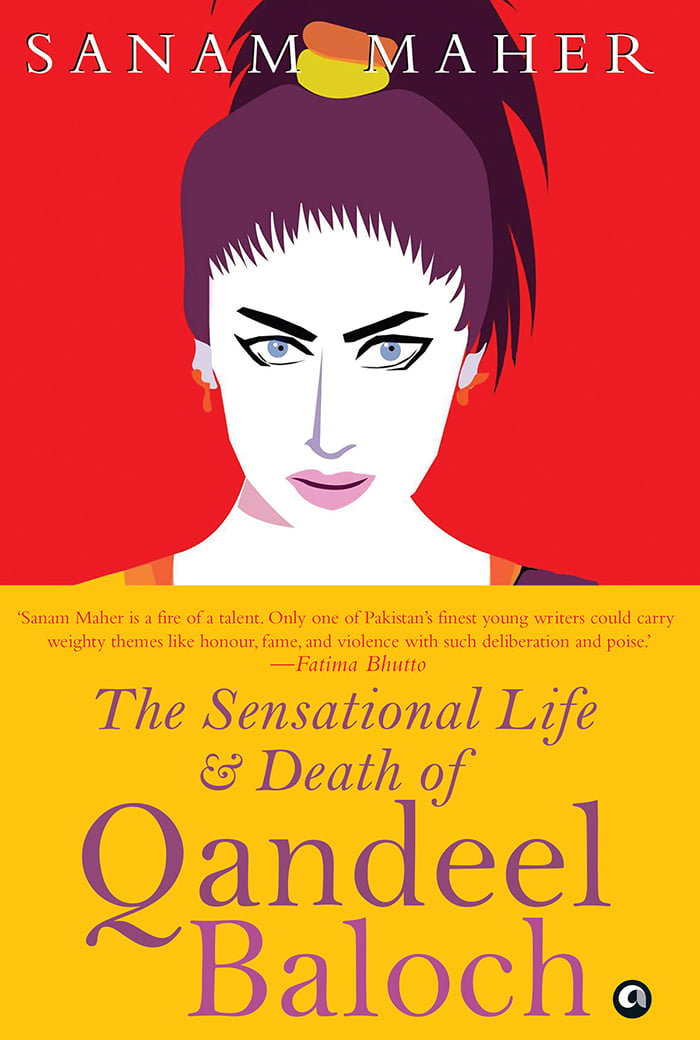

Sanam Maher’s ‘The Sensational Life And Death Of Qandeel Baloch’: An excerpt

Extracts from ‘The Sensational Life And Death Of Qandeel Baloch’ by Sanam Maher

By Sanam Maher

Main iss liye paida nahin hui thi ke kissi mard ki jooti bun ke rahoon.

‘Name?’ asks the woman sitting behind a glass-topped desk inside the Darul Aman, the government’s shelter home for women.

She gives her real name. The name her brother had chosen for her when she was born.

‘Fouzia Azeem.’

And his?’

She looks down at the baby nestled against her. She will never forget the misery she felt the day she learned she was having that man’s child. And then the love that held her so tightly within its grasp that she endured months with a man she called an animal, just for this little boy.

‘Mishal.’ The light.

~

A few days later, she is transferred to a shelter in the city of Multan. ‘My parents keep coming here for me,’ she tells the officials at the Darul Aman in Dera Ghazi Khan. ‘They just want me to go back to my husband. Mujhay yahaan khatra hai (I’m in danger here).’

From the car’s window, she sees men and women squatting on the footpath outside a mosque in front of the shelter. Some of the women cradle children in their dupattas. They sit here for days, refusing to leave without the woman they have come to claim. ‘She will run off with someone else if she stays here,’ the men argue with the shelter’s guards when they tell them to go away. ‘Hamein nahin manzoor (We do not accept this),’ the women chime in. While they wait, they watch the female guards saunter to a kiosk at the corner to buy chips, candy and fizzy drinks for the women behind the gates. There are rumours these guards keep a close eye on the women inside so they can sniff out the most desperate. ‘We have a pretty, new one with us this week,’ the guards then whisper to landlords and politicians in the city. The women are not allowed to step outside the shelter, but on some nights, with a thick enough wad of notes in the right hands, the gates are unlocked. At least, that’s what everyone says about this place.

Every day, women pound at these gates, pleading to be let inside; and they are led to Fatima’s office. She has been in charge of this women’s shelter for only a year, but she learned one thing very early on: ‘yahaan pe jo normal muashray se thori baaghi hoti hain, wohi aati hain (the women who end up here are the rebellious ones)’. But this place has a way of weakening that rebel spirit. Perhaps it is the din of wailing children—and sometimes their mothers—that makes women want to run back to whatever it was they escaped. Maybe this place makes them realize they aren’t all that special, Fatima wonders. Once your eyes get used to how dark it is inside at all times—why risk having windows you can get in or out through—you might see that there are two kinds of women who end up here: those who want to marry someone of their own choice, and those who want a divorce. None of them can stay here forever.

Some women crack in two days. Better the devil you know, they say. After they leave, Fatima gets updates on them. ‘Uss ko ghar mein bund kar diya (They have locked her in the house),’ she learns. ‘Uss ki taangein kaat di (They have cut off her legs).’ Some women follow their father’s or brother’s or husband’s earnest promises all the way out of the shelter, and then Fatima will hear, ‘Uss ko maar diya (They killed her).’

The new girl does not seem to be in any hurry to leave. Her parents travel for hours from their village to meet her. She doesn’t want to talk to them. She has no interest in any of the classes— religious lectures, handicrafts, stitching and embroidery—intended to keep these women busy. She fusses over her child and trails through the corridors crooning to herself. Sometimes, she takes requests, and then the sweet strains of a love song slip under the cracks of the door to Fatima’s office, silencing, for just a few seconds, the whine of complaints from the women who crowd around her desk like siblings snitching on each other.

At any given time, Fatima is responsible for up to forty women at the shelter, and she would have forgotten everything about the new girl, were it not for the day she gave her baby away.

She says the boy is sick. She is terrified he will die.

If anything happens to him, God forbid, they will do a case on me. I had no choice.

‘Tum kaisi maa ho? (What kind of mother are you?)’ Fatima asks with disgust when Fouzia returns to the shelter after meeting her family, her arms empty. The boy is no longer hers. She doesn’t seem to register a word Fatima is saying. ‘Just try and meet him,’ her husband had said. ‘See what I do to you if you even try.’

What have I done? Will my boy ever know his mother’s name?

Fouzia doesn’t weep, she doesn’t talk back or walk off even as Fatima berates her.

I thought when my child is older, he’ll understand, he’ll see the environment there in the village and feel that his mother was right, that she did what was right.

Maybe she has some fantasy for herself, Fatima thinks. She imagines herself living in a beautiful house, a rich woman with the world at her fingertips. Maybe she is one of the educated ones. They think they are very modern. Main parhi likhi hoon (I am an educated girl), these girls say when Fatima asks them why they ran away from their homes. Main uss mahaul ki nahin hoon (I don’t belong there). ‘Why did you do this?’ she asks Fouzia.

Even years later, she would not forget the girl’s reply.

‘I need to make my own life,’ she says. ‘Whatever I want to do, I cannot do it with a child hanging on to me. Main majboor ho jaoon gi (I’ll become helpless).’

The child could go live with his grandparents. Maybe the father would want him.

Fatima tries to argue with her. ‘But your parents could help you…’

Fouzia will have none of it. ‘No. They will not listen to me, and I will not listen to them. Bas woh mujhe meri life pe chor dein (They should let me live my life).’

They sit in silence for a moment.

‘Aap ko nahin pataa maine apnay liye kya socha hai (You don’t know what I have planned),’ Fouzia says as she rises from her chair. ‘Bas, mujhe karnay dein jo main kar rahi hoon (Just let me do whatever I need to).’

A few days later, she is gone. The next time Fatima will see her face is on the news, and by then, Fouzia is calling herself by another name, the name the world would come to know her by.

Extracted from ‘The Sensational Life And Death Of Qandeel Baloch’ by Sanam Maher with permission from Aleph Book Company.