The clock is ticking. Before the July ballot, Imran Khan, now the prime minister of Pakistan, promised to bifurcate Punjab’s 110 million population within a 100 days of coming to power. His party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), took oath in the centre on August 13. By that yardstick, there are only 54 days left for the government to form the new province of South Punjab. It is an uphill task, but if achieved, it would be historic, as for the first time, since partition, an autonomous province would be divided in Pakistan.

Till now, while PTI seems to be working furiously on achieving all other points laid out in its ambitious 100-day agenda, such as water conservation, the merger of the tribal belt and economic development, there is little clarity on what homework, if any, has been done for the administrative division of Punjab, Pakistan's most populous province.

Unfortunately for the PTI, it did not come to power in Punjab with a clear-cut majority. While it scooped up an impressive number of provincial constituencies in the general election, it needed to cobble together an alliance of other political parties and independents to form a government in Punjab. Even then, they do not have the two-thirds majority needed under Article 239 of the constitution to sail through a legislation of their choice. The PTI coalition has only 188 members in the provincial assembly. Hence, for South Punjab to be an actuality it would need to amass 245 votes, which means the PTI would be forced to reach out to its arch-rival, the Pakistan Muslim League-N as well.

In 1966, neighbouring India passed the Punjab Reorganization Act. Under it, the state of state Punjab was trifurcated. Shimla was named the capital of Himachal Pradesh and Chandigarh was the joint capital of Haryana and Punjab. To streamline the new boundaries, the provincial government of Punjab was suspended for 119 days. In the general election of 1962, Congress had won 90 of the 154 seats of Punjab and took power with relative ease. Even after the division of 1966, the party again had no major trouble ruling in the new Punjab and Haryana province.

Does the PTI envision a similar trajectory?

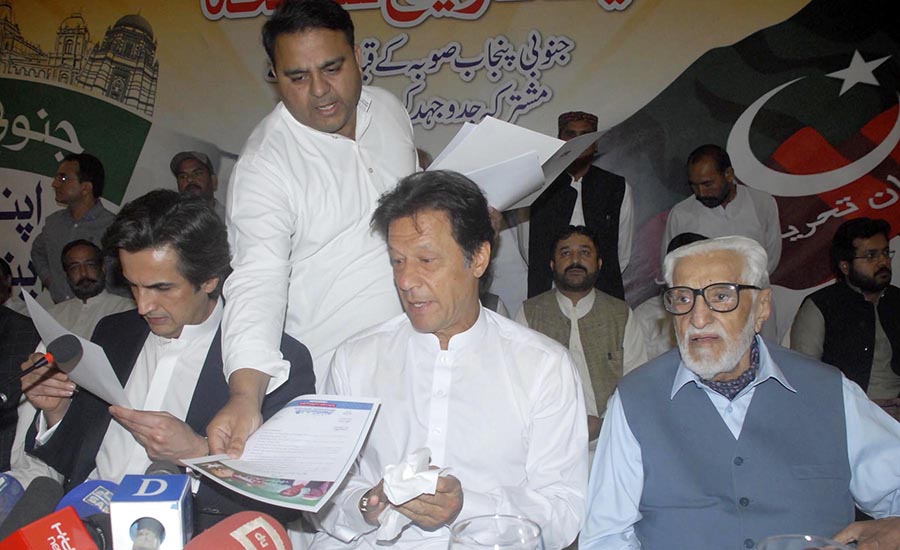

In May, handful members of the national and provincial assembly joined Imran Khan’s political party. Many of whom had defected from the PML-N and others had agreed to merge their Junoobi Punjab Suba Mahaz (JPSM), a movement for South Punjab, with the PTI. Thereafter, the Tehreek-e-Insaf formed a committee comprising of its senior-most leaders, namely Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Jahangir Tareen, Tahir Bashir Cheema and Makhdoom Khusro Bakhtiar, amongst others. Balakh Sher Mazari, an influential political figure from Ranjanpur in southern Punjab, was appointed the convenor. The committee was tasked with providing suggestions for the formation of the new province. Later, once the prime minister and his cabinet took oath, the incoming information minister, Fawad Chaudhry, told the media that a new team had been convened for further discussions on the South Punjab province. This revived group included the now foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, and the federal minister for planning, development and reforms, Makhdoom Khusro Bakhtiar.

If created, the proposed province will comprise three administrative divisions: Multan, Bahawalpur and Dera Ghazi Khan; eleven districts: Multan, Khanewal, Lodhran, Vehari, Dera Ghazi Khan, Muzaffargarh, Layyah, Rajanpur, Bahawalpur, Rahim Yar Khan and Bahawalnagar. With all the districts combined, the new provincial assembly will have 95 contestable seats (reserved seats will have to be recalculated) and 46 in the parliament.

Currently, the Punjab assembly is a 371-member house, of which 297 are elected, 66 are reserved for women, and eight are for minorities.

Now, if the PTI were to press ahead with its promise then of the 95 MPAs in South Punjab, 53 will be from the PTI, 29 from the PML-N, five from the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), two from the Pakistan Muslim League-Q (PML-Q) and one independent. (This is not inclusive of the five provincial seats vacated and to be re-contested in the upcoming by-polls). With these figures, forming a government in southern Punjab and appointing its chief minister will be a cakewalk for the PTI.

But what of the province left behind? Now that is a problem. Of the 202 MPAs left in central and north Punjab, 97 belong to the PML-N, 87 to the PTI, six to the PML-Q, one to the PPP, one to the Rah-e-Haq party and two independents. Then there are eight constituencies that are up for re-election in the by-polls. If the PTI secures even six of these eight seats then it has a shot at forming a government here too - with the help of the PML-Q. Otherwise, it might as well bid farewell to the other half of Punjab, which could comfortably land in the lap of the PML-N.

Let’s also not forget that politicians from South Punjab have a notorious history of changing the aisle. A large number of whom joined the PTI rank as late as two months before the general polls. Can their loyalty be trusted? But more importantly, will the PTI risk its government in central and north Punjab to keep a promise?