At 2:55 pm one Friday, early October last year, Shehbaz Sharif, the president of Pakistan’s second largest political party, the Pakistan Muslim League-N, was driven into an office of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), the country’s top anti-graft body.

Outside, officers of the paramilitary force and the police arranged in a semi-circle, pushing away curious reporters and onlookers. It was supposed to be a routine probe after which he would be free to leave. Officers would quiz Sharif on a failed clean drinking water project, launched when he was the chief minister of Punjab.

However, an hour later, at 3:55 pm Sharif's four-wheeler veered back into traffic, without him. The three-time chief minister was under arrest in connection with the Rs14 billion Ashiana-i-Iqbal Housing Scheme, an entirely different case from the one for which he appeared.

It was, mildly put, a rather sudden and unexpected turn of events.

Two months later, another prominent PML-N leader, Khawaja Saad Rafique and his brother, were detained by NAB. They were under investigation for embezzlement through another housing society. Before him, Qamarul Islam, who was contesting the general election on the PML-N ticket, was also cuffed by the accountability organisation.

In 2018, four senior PML-N leaders were put behind bars. None have, to date, been convicted.

"The Bureau is being used for political revenge," thundered Marriyam Aurangzeb, the PML-N spokesperson, soon after Sharif’s arrest. Her party accuses the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), which came to power in August, of using the state institution to go after rivals. But the PTI insists it is only fulfilling an old promise, to root out corruption and crackdown on financial crimes, once elected.

Justice or witch-hunt?

A month before Sharif's arrest, Imran Khan, PTI's chief and now Pakistan's prime minister, reiterated his pledge in a televised address: "No corrupt person will be let go. We will put corrupt people in jail."

Khan's purge against corruption is selective, decry opposition leaders, and a witch-hunt aimed only at settling political scores. A grievance that may not be entirely baseless.

Since last year, 22 "important inquires" have been initiated, according to NAB's own documents shared with Geo.tv. Of which majority of the politicians are from the PML-N, including Shehbaz Sharif, his sons, his elder brother, Nawaz Sharif and the former minister for finance, Ishaq Dar. Only one, Aleem Khan, on the list, belongs to the PTI.

Moreover, it seems that the pace of the investigations against ministers of the governing party are slower. No PTI leader has been arrested either, till now. While, in contrast, fresh indictments and charge sheets are prepared and leaked to the media against the PML-N more frequently.

Not surprisingly, officials of the investigative body sneer at any allegations of bias. "How can they call it political victimisation?" said a senior official of the Bureau in Lahore, who asked not to be named, as he has been directed to not talk to the media.

He insists that there is a due process and a strict procedure before a probe is launched. "Look at this folder. I get 400 to 500 complaints through post every day. Common people write to us, send us evidence of corruption every single day! We don't go looking for corrupt people ourselves."

Once a complaint is received, the officer went on, it is then forwarded to their complaint cell, comprising of five people. They have two months to pour over the documents and compile a summary. After which, a board meeting is held, chaired by the regional director general, a power point presentation made and cases shortlisted for inquiry.

Four months later, another board meeting is convened for a final decision. At this stage, a case is either disposed or converted into a reference, which is equivalent to a police First Information Report (FIR) and then the trial begins in an accountability court.

"It is a step-by-step process by a very competent staff," added the official. "As for the case against Aleem Khan, no one can dare shut it down, whether he is in power or not. We are just waiting on documents from the UAE and UK. We need them to proceed and they are just not coming." (Khan is a senior minister in Punjab. He is under probe for owning apartments in the Middle East and Britain).

Yet, the label of prejudice won't slip off that easily. The Bureau's image of a plaything in the hands of the government of the day has been in the making for the last 19 years, since the institution was conceived.

How it all began

Pakistan formed its first anti-corruption organisation in 1996, then named the Ehtesab Cell (EC), under a caretaker government. (Although Pakistan's anti-corruption law dates back to 1947, when it passed the Prevention of Corruption Act to try public servants).

The very foundation of "the Ehtesab Cell was unconstitutional and undemocratic," argues Zulfiqar Ali who authored the study, Anti-corruption Institutions and Governmental Change in Pakistan. According to Article 224 of Pakistan's constitution, a caretaker government is only empowered to oversee elections, "it cannot in principle make major policy decisions. However, in 1996, the unelected administration went beyond its mandate and established an accountability agency."

When Nawaz Sharif came to power in 1997, he further politicised the agency to serve his own interests. That year, the Cell went after leaders of the Pakistan Peoples Party, Benazir Bhutto and her aging mother. Later, Bhutto's husband, Asif Ali Zardari, was detained on corruption offenses. Later, in 2015, NAB acquitted Zardari in one of the cases, called the SGS-Cotecna case, where he was accused of awarding a government contract to a Swiss company after receiving kickbacks.

Then in 1999, military dictator General Pervez Musharraf imposed martial law. He converted the Ehtesab Cell into the present-day NAB, launching a high-profile drive to punish politicians who were accused of corruption.

The Bureau was touted as an independent organisation. But it never behaved as one. Politicians who wanted to evade arrest joined Musharraf's political party. Those who did not were harassed and imprisoned.

In the two civilian terms which followed Musharraf's exit from politics, the Bureau continued to work in the background. But its main accused were rarely politicians.

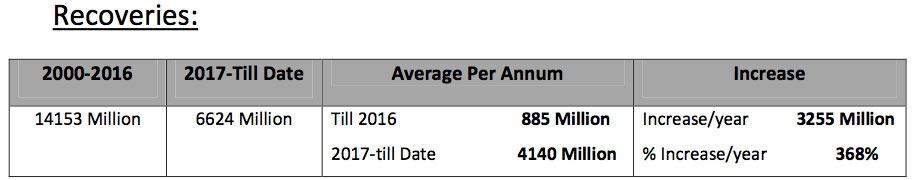

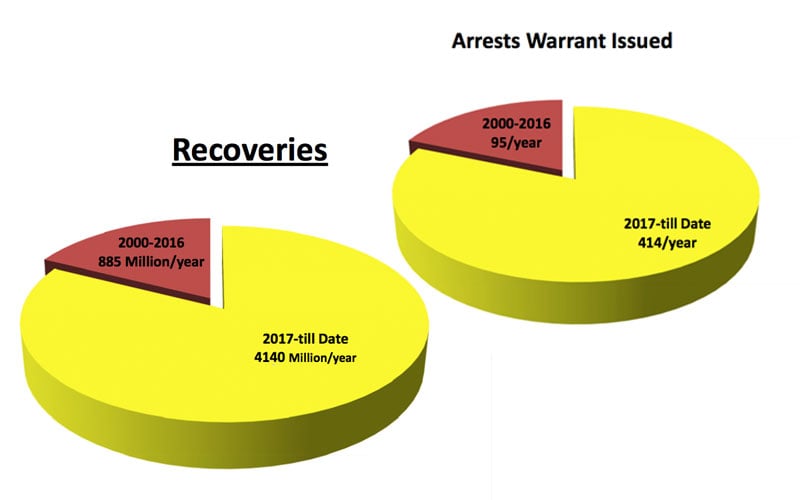

In 2015-16, for instance, it made monetary recoveries mostly from businessmen, private individuals and low-ranking government officials, according to internal documents. Interestingly, from the later half of 2017 to date, NAB boasts of increasing recoveries and arrest warrants by over 300 per cent. That is a startling uptick.

So what changed in a single year?

"For the last 19 years, no one let us work," said another NAB official, who has been with the organisation from the very beginning. "The previous government would appoint their own men, who would not let us proceed against politicians. But Justice (r) Javed Iqbal changed all that. He dug out old files and our recoveries went up."

Iqbal was appointed chairman of the NAB in October 2017, six years after his retirement from the judiciary. Under him today, the organisation has over 3,000 employees all across Pakistan, 60 lawyers, eight regional offices, and a budget of over Rs2 billion for the fiscal year 2018-19. The NAB further has jurisdiction to investigate 3,000,000 state employees, according to its officers.

Yet, outspoken opponents denounce it for only going after political elites and bureaucrats. Officials in the judiciary or the military continued to enjoy immunity from any investigation.

In fact, the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance 1999 which governs NAB, mentions that it will only proceed against a person who has retired, resigned, or was dismissed from the Armed Forces of Pakistan and makes no mention of those who have served as a high court or supreme court judge. Separately, the military proceeds against its personnel under the Pakistan Army Act 1952, which also deals with charges of corruption and corrupt practices in the armed forces. The military says it has a "strong and transparent accountability mechanism" under which it regularly scrutinises and holds its personnel accountable.

"When Nawaz Sharif was the Prime Minister in 1997, he wholeheartedly supported the corruption drive because it was going after his rivals," Irfan Qadir, the former persecutor general of NAB, told Geo.tv. "Little did he know that one day it would go after him and his family."

In July 2017, Sharif was forced to step down as the prime minister due to a Supreme Court verdict after which NAB references were launched against him. A year later, he was sent packing to jail, along with his daughter Maryam Nawaz and son-in-law Captain Safdar for one of those references. Last month, he was again convicted and sentenced to seven years in prison in another case of corruption filed by the Bureau. He is now serving his term at the Kot Lakhpat jail in Lahore.

Ironically enough, Nawaz Sharif had a golden opportunity to make changes to the law under which NAB operates when he sailed back to power again in 2013, but the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance 1999 remained untouched.

The law

The Ordinance is a problematic document. Steamrolled through the parliament by a military dictator, it gives the Bureau unbridled power to arrest anyone under probe, at any stage of the inquiry and keep them in detention for 90 days. In some cases, even the 90-day period is extended. Take senior bureaucrat, Fawad Hasan Fawad. He was arrested by the NAB in July in connection to the Ashiana housing society. After his remand period lapsed, he was sent to the lockup. Fawad, to date, has been behind bars for over six months and the Bureau has yet to file a reference against him.

Such pre-trial detentions can lead to blackmailing and browbeating people into guilty pleas. In some cases, a person may say anything to get out of jail. It further discards the presumption of 'innocent until proven guilty'.

The NAB, however, fiercely defends this right. "We only arrest very powerful politicians, who can and will influence witnesses," says a senior Bureau official.

"Take Khawaja Saad Rafique for example. He was threatening witnesses. When we would call people, they would shut off their phones. So we had to detain him to proceed with our investigation."

Rafique, the official went on, is being kept comfortably in a NAB detention cell. He then points to the screen on his phone. "Look at this. Rafique sends us a food menu every day. We forward it to his driver, who then brings his home cooked meals. Would that have happened in a state prison? It is like they are living in a five-star hotel here."

Another contentious part of the Ordinance is "voluntary returns" and "plea bargains". If a person voluntarily returns stolen money, he/she will face no repercussions. The person can, thereon, continue to hold public office or contest elections.

Plea bargains, on the other hand, are settlements reached during the investigation stage to avoid a court trial. In such cases, the public office holder will be immediately disqualified from office for a period of ten years. However, the law is rarely implemented after the money comes through. Also, there are no similar consequences for a private person.

Recently, the Supreme Court of Pakistan directed the new government to amend the sections in the Ordinance that deal with plea bargains. It reportedly told the watchdog that return of money voluntarily means an acceptance of crime and does little to curb corruption.

In response, retired Justice Javed Iqbal argued that his organisation would not have been able to recover over Rs200 billion in the last 19 years "from corrupt politicians and bureaucrats" without plea bargains.

"That's fascinating," comments former prosecutor general Qadir. "When Iqbal was a judge, I remember appearing before him in 2005 or 2006. At that time, he was bashing NAB in court. He even called plea bargains 'muk mukka'. Today, he is defending them."

An overhaul?

As the cries against the Bureau get louder, critics are asking for it to be overhauled or replaced. According to the Berlin-based Transparency International, "an effective anti-corruption agency is a huge strength in the fight against corruption – when they are independent of the government…and have the potential to hold even the most powerful people in society to account."

The ruling party insists that it is ready to do the needful. In September, the PTI constituted a taskforce to deliberate on ways to reform the National Accountability Ordinance. Talking to the media after the announcement, the law minister said that the government aims to make the NAB law more focused and effective "to counter mega corruption with checks and balances so as to avoid unnecessary harassment". (The law minister and Mirza Shahzad Akbar, the special assistant to the prime minister on accountability, did not respond to Geo.tv's requests for comments). Four months later, it is unclear what the new changes will be, if a working document has been prepared, or what suitable "checks and balances" will be put in place to prevent the politicisation of the Bureau.

But the most important question to ask is: will that be enough?