Not too long ago, when Pervez Khattak was the chief minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a 40 million-strong province, he was routinely hounded by reporters. Each time they would ask: “Name a mega project that your government has launched in the province?” And if that wasn’t a cruel enough, Khattak would then be mercilessly compared to the chief minister in Punjab, who had his name on a Metro bus, several highways and roads and an upcoming metro train.

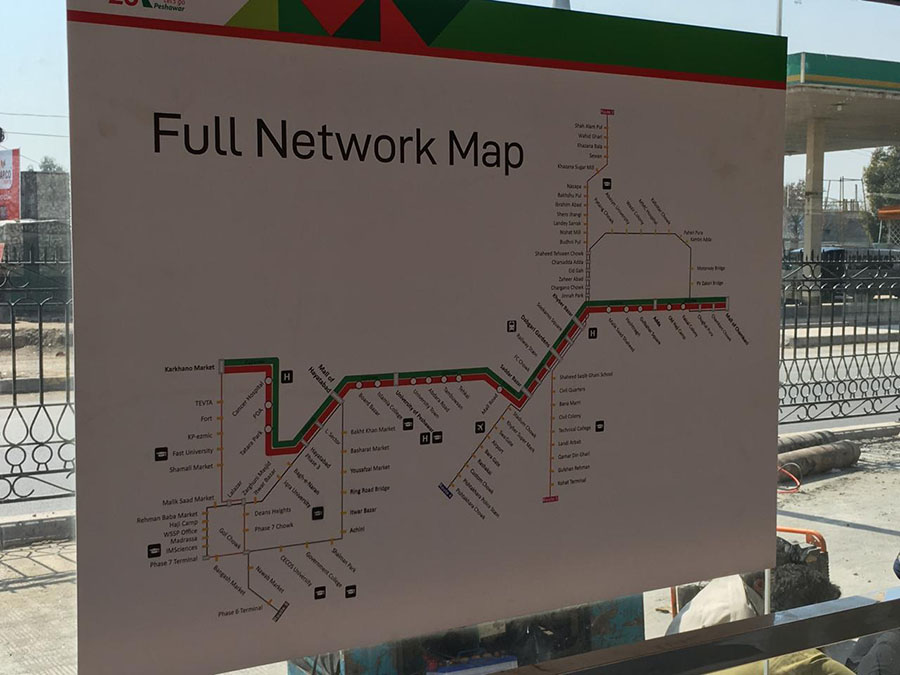

Finally, fed up, or genuinely concerned about Peshawar’s traffic congestion, the chief minister launched Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s first Bus-Rapid-Transit (BRT) line, a 26-kilometre east-west corridor in the city, designed to move thousands of passengers per day.

Interestingly, construction began in October 2017, just a few months before the general elections.

The official website of the BRT, launched soon after, referred to it as “a world-class transport service” which will generate greater “economic activity and prosperity in the city.”

Promises were made. The project will be completed in six months, Peshawar was told. But the six months came and went. Today, 17 months later work on the fixed-rail continues.

Instead of strengthening Peshawar’s public transport system, traffic is worse than before. Car owners are forced to dodge debris and heavy machinery lying open on the main thoroughfares. Pedestrians have to scramble in confusion. Overall, there is confusion and anger among the residents of the city.

Which is why one must ask, was the BRT too ambitious? No. Each day, it becomes clear that the embattled bus corridor was an ill-planned and ill-timed investment, launched hurriedly by a chief minister and his government in desperate need for a win.

Over a year later, of the total 31 bus stations, 11 are still incomplete. Work on the three bus depots, at Chamkani, Hayatabad and Dabgari is unfinished. Over 200 buses were to reach Peshawar. So far, only 21 have arrived from China.

During all of this, the cost of the corridor has shot up from Rs49 billion to Rs66 billion.

Even with this backdrop, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI)-led provincial government will be holding a “soft launch” of the BRT on March 23. As part of the first phase, only women, children, the disable and the elderly will be allowed to use the facility.

Shaukat Yousafzai, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Information Minister, admits that there may have been some hiccups, during construction, which delayed the project. Yet, he is adamant that despite the hardships, “it would be a precious gift by the PTI government for the whole province,” he told reporters.

Hiccup is an underestimation. It was more a comedy of errors. Take for instance, the story of an underpass to be built near Aman Chowk. The underpass had to be re-dug and rebuilt after the planners realized that it was too narrow for a bus to pass. There are many such examples of drawing and redrawing since the inauguration of the BRT, which in return drove up its construction cost.

“The government has changed the deadline [for completion] four times already,” said

Gulbadar, a middle-aged man, waiting for a bus, “Look at our city. It is a mess.”

Infrastructure aside, only 30 per cent of the Intelligence Transport Systems (ITS) have been laid across the city. These systems are important for the efficient running of the buses and will be used for everything, from ticketing and boarding to the actual movement of the buses.

But the planning is not a total fiasco, assures Israrul Haq, the Director General of the Peshawar Development Authority. “Over 80 per cent of the work is already done and the rest will be complete by end June,” he told Geo.tv. “We are sticking by the deadline we set in the PC-1. The BRT will be up and running by June 30.”

Daewoo, a private transport company, has been given the responsibility of operating the BRT, for which, the company has already trained over 40 drivers.

When first launched, the BRT promised - as listed on its website - to reduce travel time, and with it improve the environment and the “outlook and reputation of the city”. But the quality of life in the city has only deteriorated. Last year, hundreds of traffic police reported suffering from eye and lung infections due to the dust and smog-enshrouded air they were forced to breathe near the corridor.

In the end, traffic congestion may be a quicker fix for the PTI-government, once the BRT is complete. But the PR damage that it has caused the ruling party would be the hardest one to fix.