The dying delta and the deluged dwellers

By Oonib Azam

For locals, walking in inundated Kharo Chan was as normal as a stroll in a paved park. For a group of journalists, each step was calculated, as they would lose their footing in the waist-high water with every tread forward.

It was almost mid-September. Fear of another monsoon spell loomed large. The sun was out and bright as it peeked through dark clouds. The mighty Indus River flood had reached its final destination: the delta, where it was supposed to empty itself into the sea. The floodwater had brought with itself slippery silt from mountains, as it was nearly impossible to move without lurching.

A significant part of Kharo Chan, an area of District Thatta, comprises the Indus delta. The area paints a gloomy picture of a ghost town abandoned because of floods. Almost all shops in the main Kharo Chan market were padlocked as if there was a curfew in place. Most of the residents had already relocated temporarily.

Despite all their miseries, Umer, a resident of Kharo Chan, and his companion were absolutely unfazed. Having his white shalwar rolled up to his knees, he effortlessly manoeuvred his way around through the floodwater, hoping for it to recede soon. “It is almost after 10 years, the river water has entered the delta,” he said with a hint of hope on his face. This, he believed, would push seawater away and recharge aquifers of the deltaic land.

Kharo Chan was once agricultural land. Back in the 1960s, Umer recalled how there used to be rice harvest in the area. “The riverine water stopped flowing towards the delta and the seawater gradually swallowed up the entire land,” he said.

While floods in the Indus River ravaged everything in their way, farmers living at the mouth of the river, which is its delta, are also looking at the bright side they believe in. They say that the incoming fresh river water will push the seawater back and their lands will once again be cultivable.

Their happiness could be short-lived.

Climate-induced migration

Munawar Ali Baloch vividly remembers how on October 24, 2019, he and his entire clan left Qadir Bux Baloch, his small village situated on an island at Kharo Chan, for good.

Now in his early 40s and a trader by profession, he recalls how back in the 1990s, seawater had already devoured a huge chunk of his village, as the Indus River water flow towards its delta was hampered. The villagers, then, started losing their agricultural land.

“Until the day came when the entire land became infertile and there was no water left even to drink,” he said. Now his village is completely submerged under seawater. The riverine floods now come after decades in the deltaic region. This, he said, does not help much.

Munawar, along with all the other residents of his village, has resorted to different occupations since then and has left their ancestral profession of farming permanently. According to the Sindh government’s data, 21 out of 41 Dehs [cluster of villages] of Kharo Chan have been completely eroded by seawater.

Some 29 kilometres away from Kharo Chan lies District Thatta’s port Keti Bandar, which, almost a century ago, was famous for the harvest of red rice. “Now the land is barren,” said Yunus Khaskheli, 63, a former resident of the area. Khaskheli now lives in Rehri Goth in Karachi’s Landhi area near Phitti Creek, which was also part of the Indus delta centuries ago.

Khashkheli has worked with the UNDP and other international nongovernmental organisations as a researcher on the Indus Delta. “At least until the start of the 19th century Phitti Creek was part of Indus Delta,” he recalled, adding that even Shah Abdul Latif, the 18th-century mystic Sufi poet from Sindh, in his writings, has mentioned Jhari Creek, which flows parallel to Phitti Creek, as part of Indus Delta.

After his grandfather’s demise, Khaskheli and his family moved to Rehri Goth in Karachi and took up fishing as their new living.

The mighty Indus River

The mighty Indus River starts its thousands of miles-long journey from Tibet, close to sacred Mount Kailas. Part of its upper course runs through India; however, its channel and drainage basin are in Pakistan. The river travels more than 3,000 kilometres before culminating in various creeks of Sindh, creating a complex system of swamps, streams, and mangrove forests.

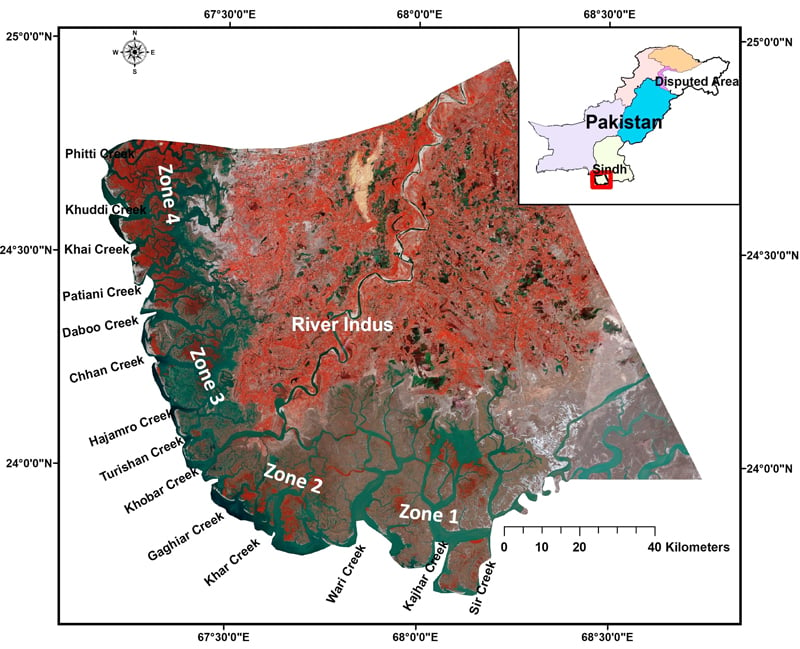

Until at least the early 19th century, the Indus Delta, which is the fifth largest in the world and has the seventh largest mangrove forest globally, was flourishing and alive with at least 16 major creeks. The wetland was designated as a Ramsar site in 2002.

Human interventions

Deltas are the ending point of rivers, where they meet the seas through creeks, which can be called their branches as well.

The first of its kind major human intervention in this delta was during the British Raj when Sukkur Barrage was constructed in the year 1932 — after that, there was no looking back.

The Indus River enters Sindh at Guddu Barrage, which was constructed in 1962, from where it goes towards Sukkur Barrage and then Kotri Barrage, whose construction was completed by 1955, before entering its delta.

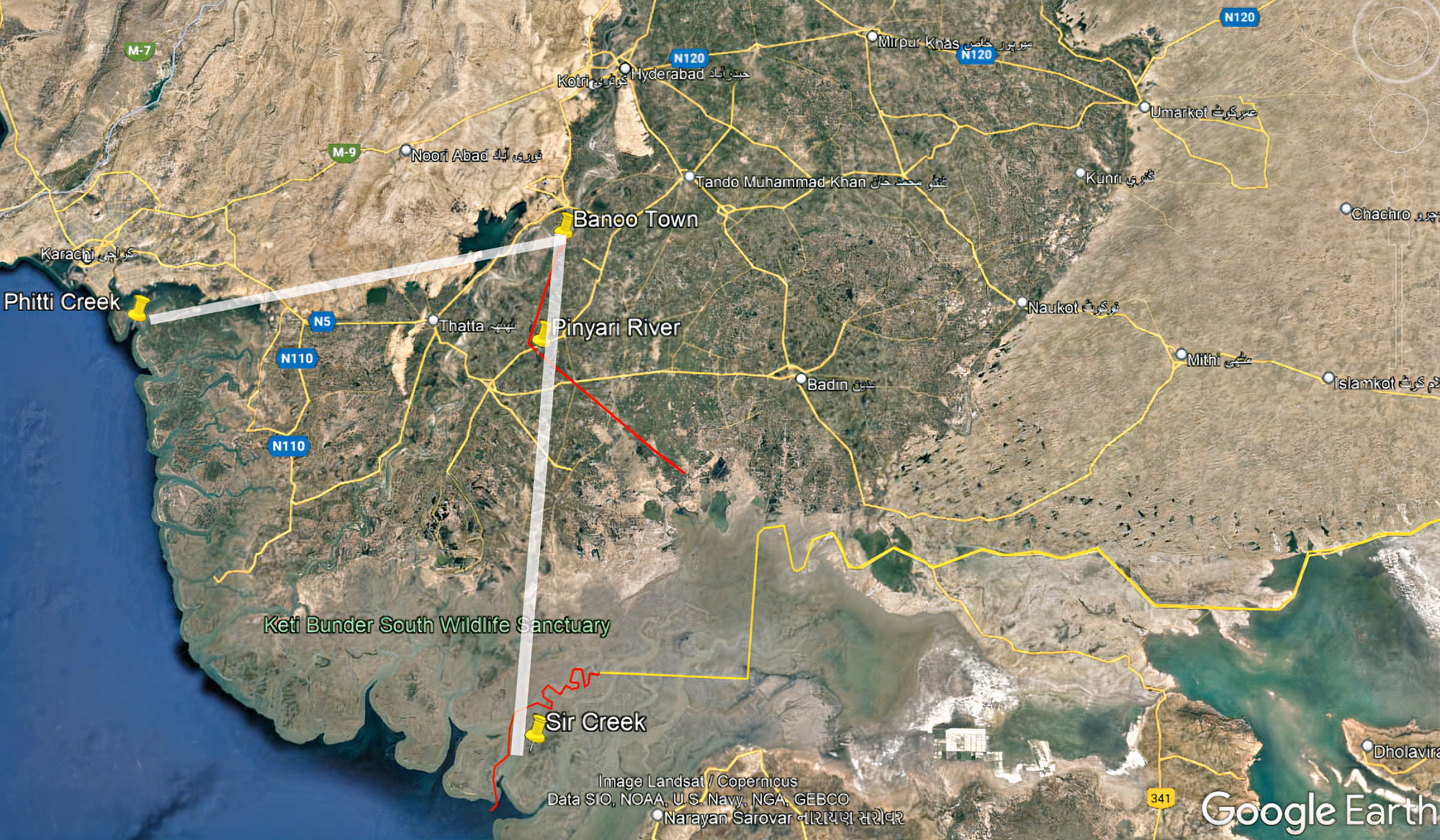

The Indus Delta spreads into Pakistan’s Sindh province from Sir Creek in the east to Phitti Creek in the west with the apex at Banoo Town of District Sujawal, Sindh, where once Pinyari River originated from the Indus River and then discharged into the sea through Sir Creek.

Sindh Irrigation Department’s report of July 2021 reads that with the construction of dams and reservoirs, the Indus River past 1960 has reduced to throw silt in the sea from 400 million tons to 100 million tons every year. “This depletion inflow of silt to sea has accelerated intrusion of seawater.”

The Senate Standing Committee on Science and Technology had already forecasted that the seawater intrusion in Badin, Thatta, and Karachi coastline may sink them in 30 and 60 years.

Professor and Dean at Sindh Agriculture University Tandojam, Dr Altaf Siyal, who is an expert in soil and water resources engineering and management, was the lead researcher of a study conducted on Indus River and its delta in 2018. He shared that the intrusion of surface seawater has degraded 42,607 hectares of Indus Delta land - a land size greater than the area of the Italian city Venice.

Out of these 42,607 hectares, 31,656 hectares of land are completely underwater. “All because of human interventions in the Indus River,” Dr Siyal says.

Original creeks

There was once a time when the Indus River had its deltaic region spanned up until Phitti Creek and Korangi Creek in Karachi.

With unabated and massive human interventions in the river, very few creeks are left.

Former Director General of the Institute of Oceanography Dr Asif Inam is a lead researcher of a study of the river titled 'The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River'.

In the study, he mentioned how the Indus delta had originally at least 16 major creeks which includes: Phitti, Khuddi, Khai, Paitiani, Dabbo, Chhan, Hajambro, Turshian, Khobar, Gaghiar, Khar, Wari, Kajhar, Sir Creek, Kori and Nirani.

As the delta is drying up, according to Inam’s study, only the area between Hajamro and Khar Creeks receives riverine water with the main outlet into the sea from Khobar Creek.

Today, the Indus delta is left with two creeks: Khobar and Khar, Siyal’s study revealed. “The active delta once occupied an area of 1.30 million hectares in 1833, which has now been reduced to 0.1 million hectares, a 92 percent reduction in the area,” the research paper said.

Using Google Earth, Geo.tv estimated that the total area seawater has eaten up surrounding Hajamro Creek, due to the stoppage of riverine water flow in the creek, is around 1541 hectares or 15.4 square kilometres. This means that the equivalent of more than 699 football fields has been claimed by seawater.

Talking to Geo.tv, Siyal shared that there was a 7.1% increase in the Indus delta’s tidal floodplain area because seawater moved inland. Tidal floodplain areas are marshy lands of any delta which goes underwater with the ebb and flow of tides.

The left bank of the Indus River, which is majorly District Thatta, is two times more affected by tidal floodplain areas than the right bank, the District Sujawal side. The then Deputy Commissioner Thatta in 2016 had written a letter to the Chief Secretary Sindh of that time, bringing up the issue of tidal floods and highlighting how Keti Bandar, Kharo Chan, and Sajanwari were in the direct line of seawater intrusion.

Unprecedented floods

The recent rainfalls in Sindh were unprecedented in many ways. Sindh Irrigation Department’s official Deedar Buledi told Geo.tv that while Sindh was grappling with floods from record-breaking rainfalls in the province, the floodwater from the upcountry entered the province, through River Indus, which exacerbated the situation.

Buledi compared these rains with the super floods of 2010 and said back then the highest water flow from Kotri Barrage was more than 1 million cusec water per second. In 2015 the highest water flow from the barrage towards the delta was around 0.7 million cusec water per second.

According to him, this time the maximum water flow from Kotri towards the Indus delta was a little more than 0.6 million cusecs per second, which was observed on September 6, 2022.

Siyal shared that 38 million acre-feet (MAF) of water flowed from October 1, 2021, to September 30, 2022, below Kotri Barrage. In the year 2010, 52 MAF water flowed during this duration. On the contrary in 2020 and 2021 hardly 2.4 MAF of water flowed from Kotri Barrage in one year.

The provincial government’s feasibility study says that there has been a drop of 72 MAF in water flow in Kotri Barrage in the last 65 years. When there are no floods, Siyal said, there’s hardly any riverine water flowing through Kotri Barrage towards the deltaic region.

International panels of experts recommended back in 2004, that 5,000 cusec water needs to be ensured to flow below Kotri Barrage throughout the year. They also stressed that the release of the total volume of 25 MAF in a five-year period should also be ensured.

This, according to Siyal, would accommodate the needs of fisheries, environmental sustainability and help maintain the river channel and would restore agricultural land of the delta. It would also help push away seawater.

Sea dike

As for the possible remedy, the Sindh government has proposed the construction of a 118-kilometre-long sea dike, embankment or a barrier near low-lying human clusters to safeguard against rising sea levels and cyclones.

The construction of a sea dike is a federal government undertaking, Raheem Bux, an official of Sindh Irrigation Department’s Sakro division, told Geo.tv. The project’s estimated cost is Rs4.5 billion, which is to be completed in one year in three phases.

In the first phase, the sea dike would be constructed from Kharseer to Kherani in District Thatta, Sakro Division, while in the second phase from Kharo Chan to Ghora Bari and in the third phase it would be built from Tikka to Joho in the District Thatta.

“The feasibility report of the project has been submitted to the federal government’s planning and development department, while approval is awaited from the Central Development Working Party,” said Bux.

Oonib Azam is a Karachi-based journalist who reports on social justice, climate change and urban planning for The News.