Green memories of a divided land

A tale of Delhi’s fragrant trees, reminisced by a Pakistani who once resided in India's vibrant, historic capital

By Maliha Khan

There is an intoxicating smell wafting through the air in Delhi at this time of the year, heady and sweet, with notes reminiscent of cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, and a hint of citrus. Some may find it intense and even seductive, while others may compare it to the fragrance of jasmine or raat ki raani (night-blooming jasmine). But this peculiar smell comes from a little-known tree called Alstonia Scholaris or saptaparni — also known as Shaitan Ka Jhad (the Devil's Tree) — in local parlance in India, owing to its clusters of seven glossy, teardrop-shaped leaves arranged around a single stem. The tree's name, saptaparni, is an amalgamation of two Hindi words, sapt meaning seven and parni meaning leaves.

Every year in October, it blooms in tight clusters of small pale-green and cream-coloured flowers that stay until December, releasing a familiar yet unique ineffable scent that pervades through the smog-filled Delhi air, especially in the evenings. Globules of saptaparni blooms disintegrate into tiny, delicate, nose-pin-like fragments, carried down by the wind almost like an imperceptible light snow.

In the sweltering heat of July 2016, my life changed when I moved to India after being born and living 22 years of my life in Pakistan. Although I went there to study for only a year, saptaparni — interestingly also known as the blackboard tree, or the scholar tree in English — was one of the many little things that made me fall in love with the country and stay longer.

The first time this enticing fragrance captured my attention was in an otherwise tedious evening, when I had gone to Nehru Place, a neighbourhood in Delhi, to get my laptop fixed. While waiting for the repairs to be done, I smelled a unique fragrance in the air when the weather had started to get a bit chilly. I followed the trail of the scent, sniffing the air like a curious little puppy, and came upon an old tree with a large canopy studded with pearl-like globules. Underneath it sat a chaiwala, surrounded by a few people holding small paper cups in one hand and cigarettes in the other. Despite being lactose intolerant, I couldn’t say no to masala chai when my friend asked me if I wanted one. I thought to myself, if standing under this tree means I can keep enjoying that sultry scent, I’d down as many cups of tea as my stomach allowed before retaliating.

Over the next few years, I lived in Delhi, and I began to wait for this scent to return every year. It was accompanied by the onset of a nip in the air, preparing one to brace the cruel Delhi winters. It also meant it was time for the season of festivities as the saptaparni blooms sweetened the air for Durga Puja, Diwali, and Dussehra — some of the major Hindu festivals. We would dress up and go pandal hopping in Chitranjan Park, or more commonly known as CR Park, in Delhi. With each tented enclosure competing for the most beautiful and adorned effigy of Maa Durga, a principal goddess in Hinduism, there would be a string of stage performances put up by residents of the local community. Countless food stalls would sell different types of food, but "non-veg" would be the most sought-after cuisine around these pandals where some people came solely for the kebabs. The sweet and slightly spicy scent of the saptaparni, infused with the otherwise sultry smoke of the BBQ, made the celebrations all the more special.

When circumstances left me no choice but to move back to Karachi in October of 2022, the fragrance of the flowers from this tree was perhaps the hardest to say goodbye to. Before leaving for Amritsar in the Innova cab, with my ten suitcases packed with six years of my life, I ran around the neighbourhood I was living in then, trying to take one last whiff of that enchanting scent and tuck it away in my memory for good. Since then, it has come to trump everything I miss about Delhi.

It has been three years since I bade farewell to Delhi, my home away from home, and with it, most reluctantly, to this sweet, intoxicating scent. When I came back, it was still hot in Karachi, and I couldn’t help but miss the nip in the air that had already descended upon the city I had to leave behind. But once the weather began to turn cooler, my search for the Devil's tree — an ancient legend lending this perennial evergreen tree yet another name — was now afoot in Karachi, as I tried to reconcile my new life with the memories I had left behind in Delhi. Once the borrowed winters of Karachi gave way to a quick succession of spring and summer, the seasons melding before one could properly enjoy the former, other trees of Karachi began to bloom, that too were reminiscent of other blossoming of Delhi trees. Suddenly, I began to miss the delicate yellow buds of the glorious amaltas that fall generously in the Delhi summers and the fiery red and orange flowers of the gulmohar that lit the skies ablaze.

My longing for trees did not stop there. Newly exiled from a home I had built across the border in India, I began to think of the banyans and peepals that once shaded shared courtyards and still grow on both sides, their roots tracing memories older than Partition itself. In 1947, when Cyril Radcliffe drew a jagged line to divide India and Pakistan, cutting through cities, villages, and even homes, fences serving as temporary borders were erected to separate people, faiths, and histories — but not the trees. Long before barbed wire and border posts, these trees connected lives, offering shade on woven charpoys and giving meaning to myths. Today, they continue to bear as silent witnesses to a divided subcontinent — one that remains ecologically intertwined even when it is politically estranged.

Remembrance of trees' past

While the trees may think that the children who once played beneath them had forgotten them, no longer visiting them, touching their sturdy, rugged trunks with their nimble fingertips, those who were forced to suddenly leave for the other side without looking back often remembered their green friends with fond memories. Then there were trees that still waited for sacred threads to be tied around them, but nobody came, for most of them had to go looking for the same trees across the border, for traditions must continue, even if one’s home and the tree outside it are taken away.

Indian author and historian Aanchal Malhotra’s Remnants of a Separation teems with anecdotes in which trees flit through memories, glimpsed between tales of homes, neighbourhoods, and fleeting holiday retreats. In her former book, released in 2017, Malhotra interviewed the survivors of the 1947 Partition, who each recollected their memories of the most gruesome and heartbreaking event South Asia has ever seen, using the objects they managed to bring along with them to document their emotions.

During the course of the Remnants, there was one particular anecdote that stood out prominently where a tree served as one of the prime objects of nostalgia, as her interviewee recounted their story of displacement. The story was of Sunil Chandra Sanyal, who migrated from East Bengal to Calcutta during the Partition. By the time Malhotra arrived to see him, age had already begun to erode his memory. However, it was his wife, Bharti, who remembered everything Sunil had told her over the years, who was now recounting his memory with their daughter, Sangita.

"I used to wonder why he would repeatedly tell me his childhood memories, with force and vigour, holding my hand and making me listen even when I had almost memorised them. Now, after nearly twelve years of him forgetting, I realise why he did it. Was it possible that he knew that one day he would lose his ability to remember? Then how would he ever have access to the past, to the gulmohar trees in the garden, to the smell of earthy àsh from the pond behind their home? Is that why he gave them to me, transplanted them? So that they would be safe—safe with someone he trusted. Did it make me responsible for keeping his childhood alive? I really wonder…"

Sangita looked at her mother, her eyes teary, her knees bent up to her chin. With a half-smile, she said, "He remembers that in his old neighbourhood there was a pomelo tree… quite a common citrus fruit-bearing tree in the area, khatta-khatta (sour-sour), and my father and his siblings would play football under the tree with the pomelo!"

Memory is a treasure even precious than all the riches of the world, and the wise know how to guard it: by passing it down. However, even if one may lose their episodic memory, sensory, and especially olfactory memory, it is not easy to let go of. That is why, despite his lapses in remembrance, Chandra remembered the pomelo tree from his childhood, the 'khatta-khatta'. It’s because trees don’t just belong to a landscape; they belong to our senses.

Urdu novelist Intizar Husain, the leading literary figure of Pakistan, too, had a deep communion with trees. Trees are a recurring and significant theme in his works, serving as a symbol for memory, a link to nature, and even an inspiration to artists. Husain’s most famous novel, Basti, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2013, is a poignant story set against the backdrop of the Partition of India and the tumultuous events that followed in South Asia. It explores themes of displacement, identity, and the impact of history on individual lives through the experiences of its protagonist, Zakir.

Zakir, newly displaced from his ancestral village, Rupnagar in the Basti district of Uttar Pradesh in India, finds himself in Lahore, Pakistan, after the Partition. Trying to adjust to a new life, missing his old room during sleepless nights, he once decides to venture out with his friend, Afzal, and instead finds himself longing more and more for the home and his childhood sweetheart he had left behind in India.

"I was remembering my lost trees. Lost trees, lost birds, lost faces. The swing suspended from the thick branch of the neem, Sabirah, the long swing, swings back and forth, ‘Ripe neem seed, when will spring come?’ — damp hair fallen forward on cheeks wet with raindrops. Long live my brother, he’ll send a palanquin for me!’ From a distant tree, the voice of the koyal bird (koel).

Interestingly, the trees in the park spark this longing in him, since before Husain’s protagonist finally took off his shoes, unbuttoned his shirt, and closed his eyes under a leafy banyan tree to reminisce about perhaps the happier days of his past, he was complaining about the lack of neem trees in the park they were in then. And how one never had to search for them in Rupnagar. “In the afternoons when the desert wind blew, and in the rainy July days, their greenness always proclaimed their presence."

Silent observers of love, violence and belongings

Malhotra's novel, In the Language of Remembering, launched most recently in 2025, not only tells personal stories and memories from survivors, but also those of their descendants, examining how Partition trauma and loss are passed down through generations and continue to shape their identities, families, and sense of belonging.

One of the anecdotes that brought me to the verge of tears was narrated by the artist and poet, Jagdeep Singh Raina, to the author about the aftermath of his grandmother’s sister’s abduction during the Partition.

“After Partition, when my paternal grandfather was dividing time between Srinagar and Jammu, he heard news of a distant cousin who had been abducted during the violence. She now lives in Pakistan, has a family there, but she would come to the border and wait to see if anyone appeared on the other side.

“W-what border was this? ‘Jammu–Sialkot. My grandfather went to meet her once.’

"A single, well-landscaped road runs through the border post.

"The Indian tricolour is painted on one side, and a Pakistani star and crescent moon on the other. Identical trees fill the landscape beyond.

"He stood in India, and she in Pakistan, and they just waved at one another. They were family, separated by a border, a line, a road.’"

What struck me the most was that the identical trees that filled the landscape on both sides of the border silently wept because all they could do was stand there and do nothing: just watch two people bound by blood, unable to embrace because there was a boundary they couldn’t cross. Even as the roots of the trees met somewhere underneath the shared ground, the roots of both the people standing above them were cut off despite being shared.

But trees of the subcontinent have seen far worse than just people bound by blood not being able to embrace each other. They have been a witness to actual bloodshed and terrible violence during not only the Partition riots but also well before that. When the freedom movement in India began, the British would nail freedom fighters to a tree, or worse, sometimes hang them from it to make an example of them for other members of the independence struggle. During the Partition riots, trees also acted as a camouflage, shielding the houses and their occupants from rioters. This is the legacy of the tall trees of the subcontinent, some of which concealed what could have been destroyed, while witnessing what actually was.

In those horrifying times, trees served as loyal guardians of treasures, belongings too hurriedly buried in the backyards of their homes, temporarily by people who thought they might come back to dig them up and claim the remnants they left behind. Priyanka Sabarwal’s family migrated from Gawalmandi in Lahore to India during the Partition, and as a young man, her granduncle, not being sure if it was safe to take his box of ‘treasures’ with him, buried it underneath a tree in their backyard. What’s most endearing is that amongst those items — in a box of most important things — were: “the razor his father gave him for his first shave, his mother’s gold earrings because he lost her fairly young. A bottle cap with no clear significance, a love letter he wrote to a girl he liked in college … but never sent, perhaps, but one that did include a Ghalib couplet, though. There was also a ticket stub – from a music show or movie. And a pen he won as an award at school, along with some coins he ‘earned’.”

I wonder if that tree still remains there with the box of treasures buried deep beneath it, just as all the memories of Partition keep buried deep somewhere in our minds as we go on with our lives. But there are those who remember and strive to keep them alive through language and art.

The language of leaves

Trees have been deeply embedded in our subcontinental poetic tradition. "While many readers of Urdu poetry are familiar with the archetypal romance between the bulbul (nightingale) and the gul (rose or flower), the image of trees in this metaphorical garden has also inspired poets across centuries," writes Syed Moosa Gardezi, writer, environmentalist, educator, and also a poet under the nom de plume SM Karachvi. Through extensive research on his writings on Urdu poetry, I came to discover Iqbal’s engagement with nature, particularly trees. For example, in Baang-e-Dara, his first collection of Urdu poetry, published in 1924, the first poem Himala reflects a romantic and nationalistic connection with nature. Later, in Parinday Ki Faryad, the baagh (garden) becomes a symbol of freedom from colonial oppression.

However, an incidentally rare translation of a poem by the Umayyad Emir Abdur Rahman I in Iqbal’s Baal-i-Jibril, published in 1935, was once brought to my attention at a dinner party that I attended at my brother's in-laws' home. His wife’s taaya (elder uncle), a lover of shayari (poetry), brought up this poem titled, The First Date Tree Seeded by Abdur Rahman I and translated by K A Shafique.

The recitation of these verses touched something deep inside me and a flood of memories, not just of my own, but those of a collective washed over me as I was silently swept away with a profound emotional experience in exile, with the date tree not just symbolising nature but a connection to the homes so many of us on either side of the Indo-Pak border had left behind. Though borderless winds from either side may nurture the trees that were abandoned, the verses even stirred in me the pain, inner turmoil, and longing of the trees for their planters to return to their birthplace, even if for a momentary touch on their now sturdy barks from years of hardened hearts.

"Trees are like our collective mind; they retain the memories," wrote Intizar Husain in a column in 1964. Of the many columns that Husain sahib wrote on trees, the destruction of trees often represented the erasure of history and memory in an industrialising society that has little regard for the past. In this particular column, he recounted the incident about an old tree on Lahore’s Mall Road that took one to Anarkali Bazaar, which eventually became a victim of the Lahore Corporation. When he brought up the matter with a barrister short story writer, the latter made light of the matter, saying, “You are suffering from nostalgia. Mourning forever the loss of tamarind [imli] trees in your hometown, you have now started becoming emotional about the trees in this city. But this is not a small town; it’s a new city, and we are living in the twentieth century.”

However, there are still those who are defiant in keeping the nostalgia alive. One such individual was Delhi-based journalist Somya Lakhani’s grandfather, who migrated to Delhi from then North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). In order to keep the memory of the dialect of his language that he spoke in his former home alive, he would, for example, "never call a tree ped, as we normally would in Hindi. He would call it darakht,” Somya recalls in her interview with Malhotra for her book, In the Language of Remembering.

Rootedness and rootlessness

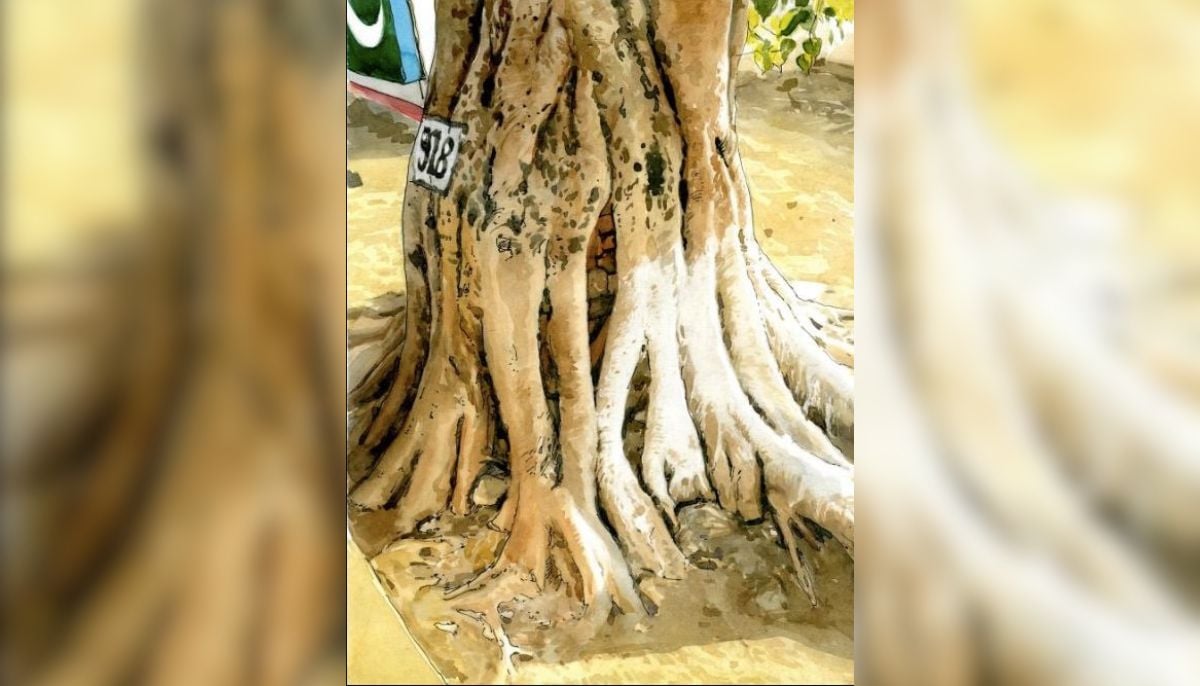

Not many know of this, but there is a peepal tree, also known as the 'Sacred Fig', which is exactly on the 'zero line' of the Indo-Pak border in the Suchetgarh area of the RS Pura sector in Jammu and Kashmir. Fortunately, neither the Indian Border Security Forces nor the Pakistani Rangers has cut the tree that seems to have existed for at least 100 years, long before even the Partition happened. In fact, they have painted the serial number 918 — a sign of the boundary — on its trunk, accepting it as the new boundary pillar.

Asif Noorani, a Pakistani writer and journalist, once while crossing the border, remarked on the very same tree in his Dawn, 2015 article, writing, “Nature doesn’t recognise any man-made boundaries, otherwise the over-100-year-old tree, with its trunk a few inches on the Indian side of the white line, would not have allowed its branches to spread over Pakistani territory, nor would its roots have pierced our soil. Thanks to the Radcliffe Award, many such trees must be enjoying what you may be tempted to call 'dual nationality'."

While Noorani writes about our shared rootedness, Nina Sabnani, an Indian artist and storyteller, uses the metaphor of a banyan tree in a paper she wrote titled “Roots in the Sky”. Like a banyan tree, whose roots hang in the air, she argues that when you can’t really trace your roots back, you become an outcome of a fractured history. Memory then becomes a place of anchor where one can always go back to and look for the roots that tie us to each other.

That is what prompted me to write this essay, a memory of a fragrance, a tree, a neighbourhood, a city that is no longer mine. But at the start of every winter, when there is a certain nip in the air at night and one just knows that winter is on its way, my mind is flooded with that strong and heady fragrance like an expensive head-turning perfume with fresh green notes, wondering why perfumers around the world still haven’t packaged it into a fancy bottle for us to cherish it all year around.

Three years since I returned from Delhi, every time I am out and about in Karachi this time of the year, I can smell "that scent". It feels as if my mind is playing tricks on me because I desperately look around from the moving car I am in to catch a glimpse of Delhi in Karachi. However, unable to spot it, I am left wanting more as the smell of Delhi winters fades away once the car turns a corner. Maybe my quest for this bewitching fragrance in Karachi represents my intense longing for the days gone by, or for winters that are not delayed and borrowed as they are here. But perhaps, most of all, my search continues because I fear the loss of memory — of not only the scent but my 'Dilli'. If only I could find the tree, I’d have my little corner of Delhi in Karachi, at least during its fleeting winter months.

Maliha Khan is a Karachi-based writer. She is a 2022 South Asia Speaks fellow and is currently working on her first book about her experience of living in India as a Pakistani. She posts on X @malihakhnwrites and Instagram @malihakhanwrites

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv