As summer opens gates of hell on cities, heatwaves get deadlier than ever

We must delve into escalating threat posed by unusually extreme summer and find ways for citizens to grapple with climate that refuses to relent

In the scorching urban landscapes of the globe, a relentless force continues to shape the lives of millions: rising temperatures and the ever-intensifying heat waves. These urban climates, once familiar and predictable, have now become zones of uncertainty and discomfort.

We must delve into the escalating threat posed by the unusually extreme summer and find ways for the citizens to grapple with a climate that refuses to relent.

Beyond the traditional discourse of climate change, we should navigate the intricate webs of socioeconomic dynamics, cultural practices, and political landscapes that contribute to the complexity of this pressing issue.

From the crowded streets of Karachi to the bustling markets of Mumbai, we embark on a journey that illuminates the stories of resilience, adaptation, and urgency in the face of this formidable challenge.

We should eschew simplistic narratives and embrace a nuanced exploration of the urban heat crisis. We must move beyond viewing rising temperatures solely through the lens of environmental science and acknowledge the entanglements of urbanisation, poverty, and social inequality.

Within these scorching cityscapes, the impacts of heat waves reverberate across the social fabric, affecting marginalised communities disproportionately.

The urban poor, often residing in crowded and under-resourced neighbourhoods, bear the brunt of the heat, their already vulnerable conditions are exacerbated by inadequate infrastructure, limited access to cooling technologies, and a lack of green spaces.

Global recognition, local ignorance: addressing gravity of situation

Amidst escalating temperatures and intensifying heatwaves worldwide, local action is crucial despite the lack of sufficient recognition. The recent release of an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report emphasises the urgency of addressing climate change and specifically heatwaves. While the global community acknowledges the severity of rising temperatures, our country has often overlooked their long-lasting and devastating impact on our lives and communities.

By treating these trends as temporary events, we fail to grasp the seriousness of the situation. It is essential to learn from global recognition and intensify efforts to understand, mitigate, and adapt to the pressing challenges of rising temperatures in our cities. Recognising the gravity of the situation is the first step towards implementing effective strategies that protect our future well-being.

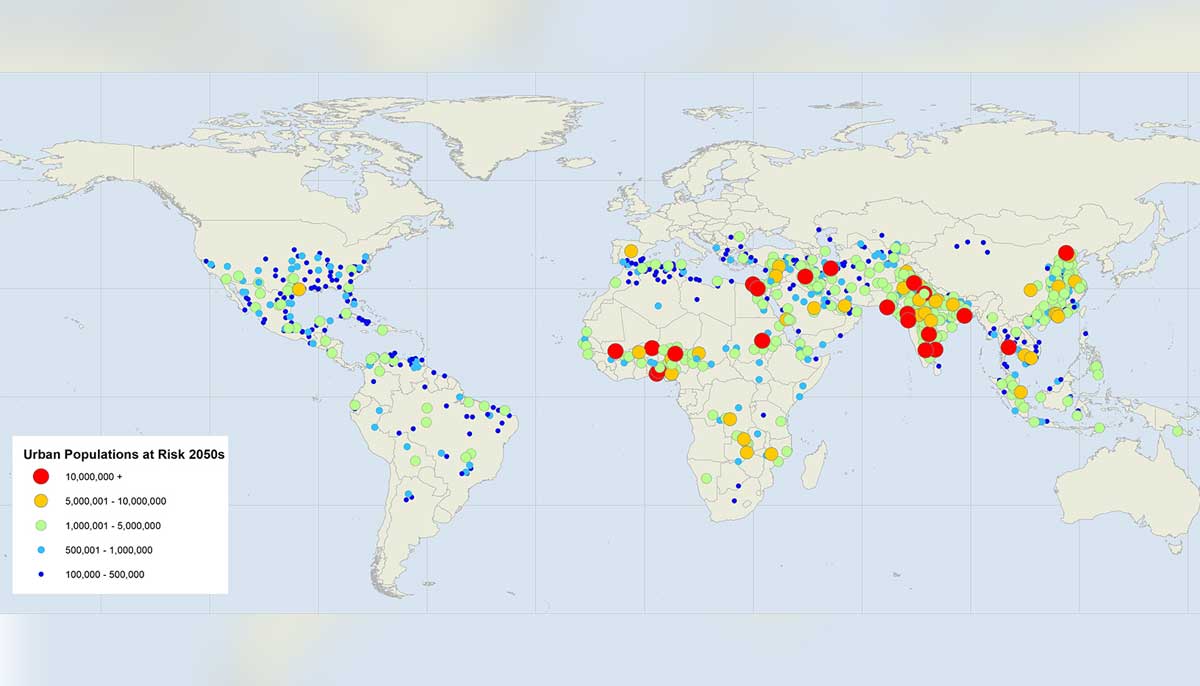

"Globally, by the 2050s, over 1.6 billion people living in over 970 cities will be regularly exposed to three-month average temperatures reaching at least 35°C," the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) mentioned. To put this in perspective, that is equivalent to more than 40% of today’s total urban population.

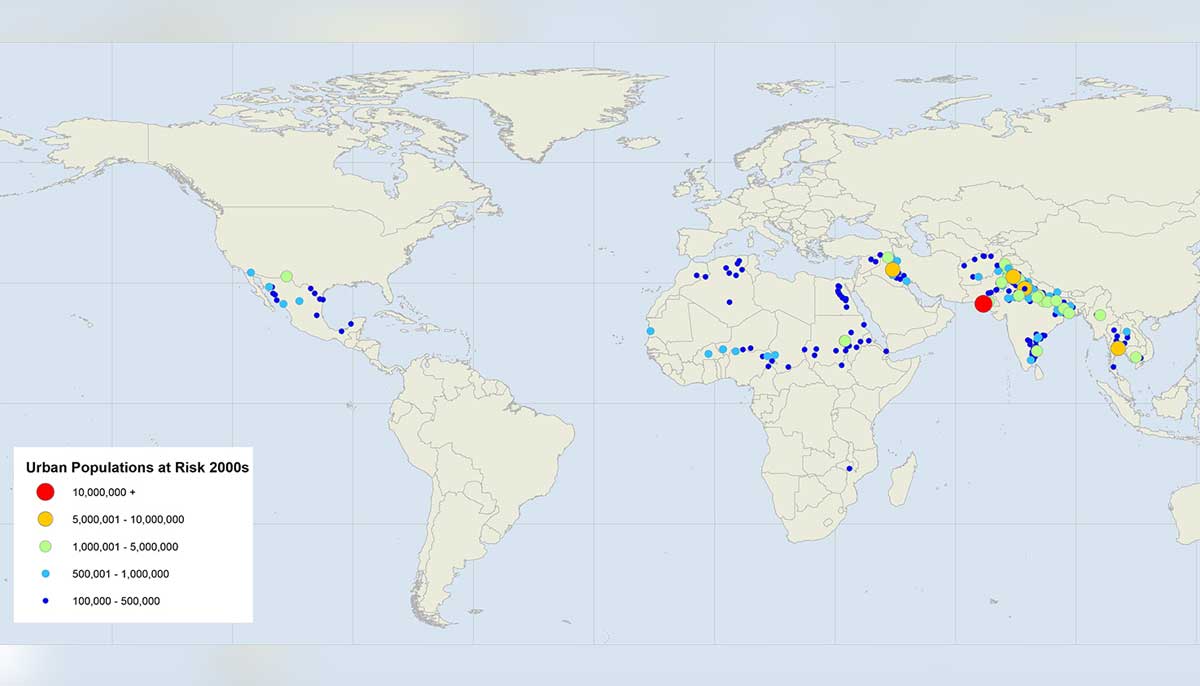

Today, around 200 million city-dwellers in over 350 cities live with summer temperature highs of over 35°C. Even at this level of exposure, heatwaves are the deadliest of all climate risks. Average high temperatures of 35°C will mean that heatwaves will become far more intense.

The IPCC report on Global Warming of 1.5°C stated: "Global warming of 2°C is expected to pose greater risks to urban areas than global warming of 1.5°C."

The extent of risk depends on human vulnerability and the effectiveness of adaptation for regions — coastal and non-coastal, informal settlements and infrastructure sectors such as energy, water, and transport.

The research conducted by C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, also shows that regions with fewer cities at present — dealing with extreme heat, average summertime temperature highs of 35°C — will see exposure rise dramatically. Over the next 30 years, 90% of urbanisation is expected to be concentrated in Asia and Africa alone, as shown below in the map of urban populations at risk from heat extremes during the 2050s.

Disproportionate impact of heat on Global South cities

Cities in the Global South are facing severe heatwaves with alarming consequences. Mumbai in India and Karachi in Pakistan experienced scorching temperatures, causing disruptions to daily life and posing health risks. These cities, along with others in the Global South, are witnessing devastating impacts due to heatwaves including productivity loss, strained infrastructure and threats to public health.

Last month, the UN’s weather agency, World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), warned that the return of the El Niño climate pattern later this year is highly likely and the world could face record temperatures in 2023. Meanwhile, extreme humid heat in South Asia in April 2023, driven by climate change, posed a significant threat to vulnerable communities.

India experienced its highest average maximum temperature in February 2023 since 1901, reaching 29.54°C. In April this year, a prolonged heatwave affected the states of West Bengal, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, with daytime temperatures consistently reaching 40°C, surpassing the seasonal average by 5°C.

In Pakistan, the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) predicts a neutral El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) state for the upcoming May to July season, which may transition towards the El Niño phase towards the end of the season. Throughout most of the country, seasonal average temperatures are expected to remain in the typical and higher-than-typical seasonal range.

Beyond temporary measures: recognising long-lasting Impact

Heat-related deaths disproportionately affect the urban poor, outdoor workers, and low-income communities in Pakistan and India. These marginalised groups face challenges such as electricity load-shedding, water scarcity, inadequate ventilation and limited access to green spaces.

In Karachi, the consequences of heatwaves are profound for vulnerable communities. Impoverished neighbourhoods lack the resources and infrastructure to cope with rising temperatures, leading to health risks, livelihood disruptions, and socioeconomic disparities. Comprehensive strategies are needed to address the long-term effects of heatwaves on the city's vulnerable population.

Several international and local organisations in Karachi work tirelessly to mitigate heatwave risks, providing ambulance services, medical assistance, and relief efforts. However, state institutions have minimal involvement, lacking permanent infrastructure and policies to effectively address heatwaves and rising temperatures in the city.

Karachi conundrum: a case study of inadequate heatwave response

Previously in Pakistan, heatwaves were not considered recurring climate disasters but rather temporary weather anomalies. However, with the increasing temperatures and heatwaves, there has been a notable shift in attention. In the southern port city, the focus of disaster management discussions was primarily on urban flooding and heatwaves were not included in the multi-hazard contingency plan for the Sindh province in 2013.

However, the devastating heatwave of 2015 sparked discussions on recognising rising temperatures and developing a comprehensive plan for heatwave management. As a result, the Karachi Heatwave Management Plan was established in 2017.

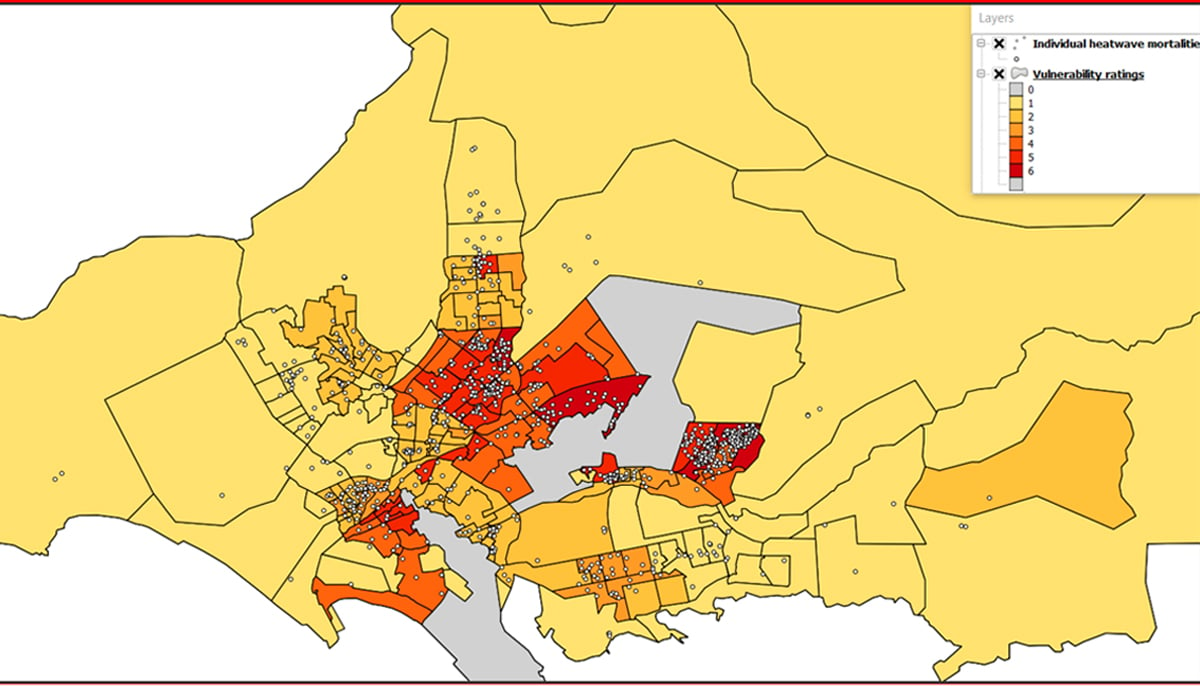

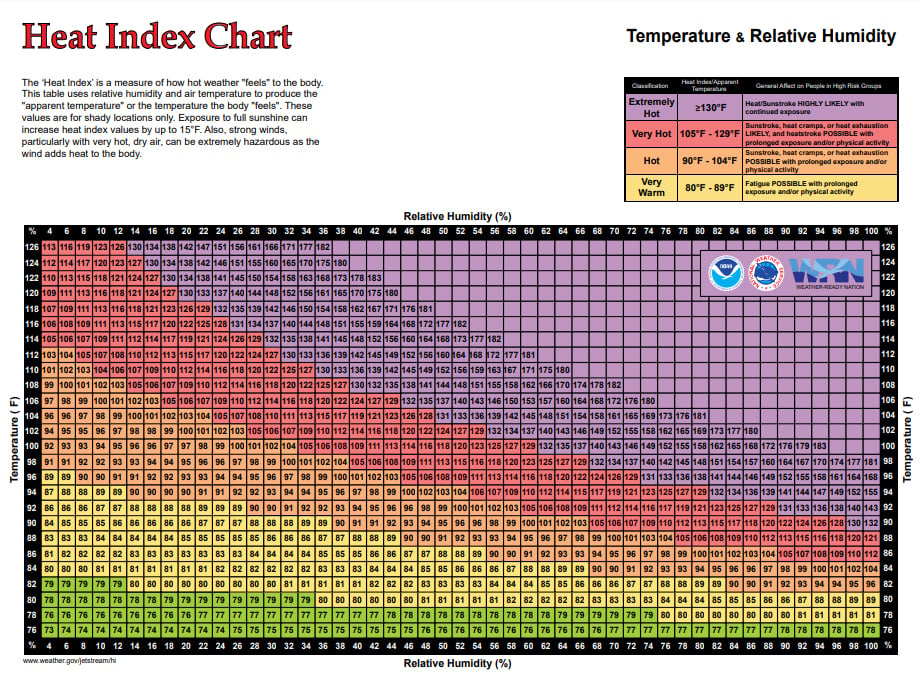

Residents of the metropolis experienced an exceptionally severe heatwave in June 2015, coinciding with the month of Ramadan. This heatwave was considered one of the deadliest in Pakistan in half a century. During the period of June 19 to 23 in 2015, the official death toll reached 1,200 — unofficially estimated to exceed 6,000, as temperatures reached 44°C, with a heat index as high as 66°C, as per the US National Weather Service’s heat index.

It is worth noting that these temperatures were not unprecedented in the city's history, as records indicate maximum temperatures of 47°C in May and June of 1938 and 47°C in 1979. However, the lethal impact of the heatwave in 2015 was extraordinary. Most fatalities occurred in low-income areas, affecting vulnerable groups such as workers and homeless individuals.

Although limited official data hinder our understanding of the specific causes, various factors associated with the natural and built environment, such as population density, housing conditions, access to basic amenities, and workplace environments, likely contributed to the heightened impact of high temperatures during the heatwave.

In a recent study conducted by the Karachi Urban Lab, titled Designed to Fail? Heat Governance in Urban South Asia: The Case of Karachi, it was revealed that the port city has experienced a significant rise in temperature over the past six decades. Specifically, the study found that nighttime temperatures in Karachi have increased by 2°C to 4°C, while daytime temperatures have risen by 1.6°C.

These temperature increases surpass the global average temperature change observed during the same period. The findings shed light on the pressing issue of heat governance in Pakistan's largest city, emphasising the need for effective strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts of rising temperatures in urban South Asia.

Shifting from emergency to sustainability: declaring extreme heat waves as ‘disasters’

In Pakistan, like other countries, heatwaves are not officially classified as natural disasters, but rather as temporary weather extremes. Unlike natural disasters such as floods, storms, or earthquakes that have immediate visible impacts and mobilise institutions for response, heatwaves may not have an immediate effect.

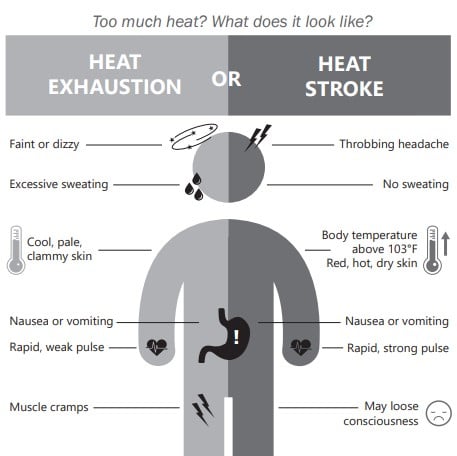

Heatwaves can complicate health conditions, particularly for the elderly, and even lead to the emergence of various diseases. In some cases, the impact of extreme heat may worsen or improve health in the short term, but over time, it can contribute to the onset of various diseases.

A heatwave is defined by the WMO as five consecutive days with an average maximum temperature exceeding 5°C. However, it is important to note that the definition of a heatwave varies based on local weather conditions and lacks universal standards.

Reports on heatwaves in Karachi highlight the difficulties posed by extreme heat and high humidity, known as "humid heatwaves," but there are no specific criteria to classify them accurately. The management of heatwave disasters in the southern port city involves different institutions at various levels, but the effectiveness of these institutions is questionable.

The District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) lacks infrastructure, and other state institutions have additional responsibilities, limiting their capacity to address heatwave challenges. There is inconsistent inclusion of heatwaves as disasters in NDMA reports, indicating a need to recognise heatwaves as a national-level disaster and activate relevant institutions accordingly.

Muhammad Toheed is an urban planner, geographer and Associate Director at Karachi Urban Lab, IBA. He tweets @UrbanPlannerNED

— Banner and thumbnail illustration by Aisha Nabi