Can Karachi be a bicycle city? Lessons from The Netherlands

Step outside in Utrecht or Amsterdam, or any other Dutch city, and what you see, experience, feel, and hear is what a cycling city is. People of all ages, abilities, and economic means are immersed in using the streets on a bicycle. The diversity that shines in cycling cities can’t be experienced where cars dominate.

If one has a pair of shoes, a bicycle, a wheelchair, or some other mobility device, one is seen using the streets, squares, and sidewalks just like anybody else.

In this piece, Geo.tv explores if Karachi can be a bicycle city, and what lessons can be learned from other similar cities to help it move to a sustainable, green model that is beneficial for the environment, people, and the community at large.

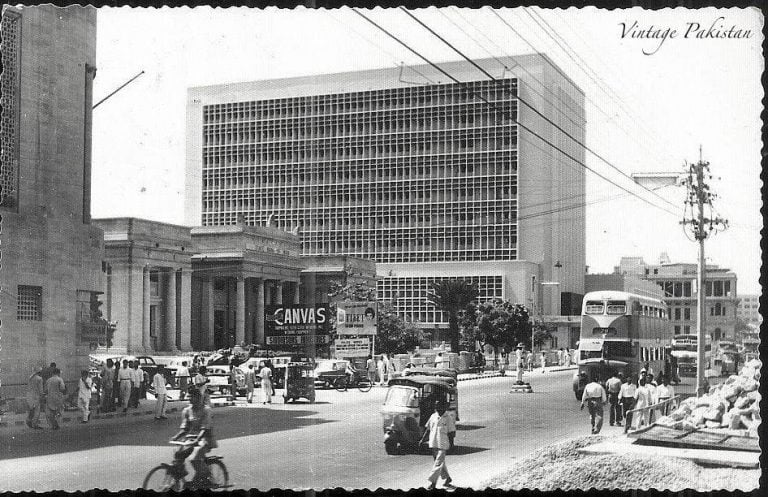

Karachi, where bicycles once reigned supreme

Arif Hasan, eminent architect and urban planner, fondly recalled the time when many in the city by the sea would ride bicycles. “I would ride a bicycle, myself, till the mid-1960s,” he shared, mentioning that the cycle had to be registered, in the absence of which challans would be issued, or if the two-wheeler had a missing headlight.

“I have been issued challans quite many times for I would have someone sitting on the handlebar of the bicycle,” Hasan enthusiastically mentioned.

Dr Noman Ahmed, professor and dean at the NED University's Faculty of Architecture and Management Sciences, and an architect and urban planner, echoes what Hasan shared.

“Bicycle was an integral part of our everyday life when we were children and teenagers. It was a mode of mobility, as well as a mode of instant joy for us,” he said, talking about the ‘prized possession’. “We would cycle our way to school, and anyone doing so was considered privileged.”

And then the city started to expand. Hasan explained how bicycle use, moving beyond the 1960s, started declining.

“The city began spreading, and distances increased, with a running circular railway as well as a bus service. People now had options to choose from. The buses were good, punctual, and comfortable with uniformed conductors, so people didn’t feel the need for bicycles. However, for shorter distances you can, till today, see people using their bicycles,” he said, adding that the current traffic in the city has worsened so much that people have safety concerns when cycling.

The Netherlands and its bicycle city model

Geo.tv reached out to Chris Bruntlett, Marketing and Communication Manager at the Dutch Cycling Embassy, to discuss how The Netherlands had its "light bulb moment".

“The road safety situation in The Netherlands was quite staggering in the early 1970s. There were 3,000 Dutch dying per year at the hands of the automobile out of which 450 were children, and this was causing much stress amongst the population,” Bruntlett highlighted the turning point for Dutch society.

“The people organised themselves against the rise of the cars and told their mayors and city councillors that they wanted something different, especially for child safety for they were losing space to walk, cycle or play on the streets.”

When the decision-makers realised that the car-based model was a one-sided monopolistic transportation system, one that is fragile and prone to outside shocks and interferences, like the 1973 oil crisis, that’s what created an inflexion point — a turning point for Dutch society.

“Buildings were being demolished, streets and motorways being widened, canals being filled — all for car-centred development, but then the priorities were realigned,” Bruntlett described the aim was not to build a car-free society, “but to build a more balanced street and mobility network where walking has its place, cycling and public transportation has its place, and the car is there for people who want to use it, but it’s not required to participate in society.”

The transition to a cycling paradise wasn’t a smooth path. “There were lots of bumps along the way. The business community in certain instances rallied against cycling infrastructure, and this was a very closely fought political struggle within the cities,” Bruntlett highlighted.

“One advantage that The Netherlands had was its cycling culture that was handed down from the parents to the children. So the parents still had that living memory from what their streets looked like before the cars came to power, so it was easier to push back and start growing cycling again," she added.

A regular sight in The Netherlands is to see children as young as seven or eight using cycle paths without any guardians by their side. “The demographic that cycles the most is the 12-18 age group. Nearly two-thirds of all their journeys are made by bicycles because they don’t have a driver’s license so cycling becomes their means of access to the city. The second demographic that cycles the most is the 65-75 age group.”

The Dutch have developed an interesting model which is not about creating a bicycling city but a great public transport where ultimately everyone benefits.

Can Karachi be a bicycle city?

Keeping in check the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 11 ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ in check, Geo.tv enquired from Hasan what steps can be taken to make Karachi sustainable. “For me, a city can’t be sustainable and green without equity and justice,” he said, as for Hasan, bringing these two elements is pertinent to move the city to a sustainable model.

Karachi Urban Lab Director Dr Nausheen H Anwar, who is also a City and Regional Planning professor at the Institute of Business Administration in Karachi, stated that a sustainable, green city model must take into account the voices of ordinary citizens.

“Karachi as a bicycle city is a viable model if the local government has a stake in it. It is important to make the poor people’s voices count. There must be real transparency in the budgeting and financing of such models, so that money is targeted toward projects that will benefit those who are the 'real' beneficiaries. Sustainable green models are valued but only if they don't become a driver for 'greening gentrification'," she said.

Dr Ahmed pointed out that a large segment of the city's youth accepts the reality that some of the common attainments like automobiles and motorbikes are not necessarily an example of sustainable living.

“Looking at the overall number of passenger trips we have in the city, about 30 million per day, let’s say half of these trips are shifted from other modes of transport to bicycling, can bring about enormous environmental improvement. Ordinary interventions can be useful for instance identifying certain roads and pathways that could be exclusive for cyclists,” he said, reiterating Dr Anwar’s idea of including the common man, the user of the public transport system to be part of the decision-making process.

Hasan, mentioned the walkable aspect needs to be added to the city’s infrastructure. "A majority of Karachi’s population walks as per Japan International Cooperation Agency’s study from 2004. I’d recommend making the city walkable for those who want to walk!"

As for steps to make bicycling a success, Hasan added, “Five Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) projects are being worked on, with each if a bicycle stand can be made, people can come on their bicycles, park them and complete their remaining journey on the BRT,” he mentioned this being on the cards, but questions if this will be implemented.

Is there a quick fix to this? “An exclusive track for bicycles from Surjani Town to I. I. Chundrigar Road will have many use the track, but who’ll manage it?” he retorted.

Lessons to learn from cities in The Netherlands

It is easy to become discouraged when one comes across a 50-year timeline that worked for the Dutch to set up successful bicycle-friendly cities.

“What I do want to stress is that the first 20 to 25 years of those 50 years were spent experimenting and innovating because there was no handbook or blueprint to building a cycling city,” Bruntlett said, emphasising on how the Dutch, through trial-and-error, stumbled across strategies and principles that were ultimately successful and were then applied in an accelerated and strategic manner.

Mentioning his favourite statistic, Bruntlett said: “Half of all cycling infrastructure that’s been built in The Netherlands was built in the last 25 years, and that’s a blink of an eye when it comes to urban planning and city building. There’s no reason why anywhere else this can’t be done if the people are as committed to making this happen.”

Bicycle cities – equitable cities?

Cleaner, equitable, environment-friendly cities are synonymous with bicycle cities. The quality of life of people who choose not to cycle is also improved because of those who do. “A bicycle is a great machine for equity, and for people with lower incomes to continue accessing the city and participating in society,” Bruntlett commented on the immense benefits of cycling.

Highlighting how cycling not only preserves life but extends it too, he mentioned, “As per the last count rates of cycling in The Netherlands 6,500 premature deaths were prevented per year which are equivalent to € 19 billion in healthcare savings which is almost 3% of the GDP.” All by giving people an active way to move around their city.

Not only does cycling make The Netherlands a cycling paradise, but also a driving paradise making it a win-win for all. It is time the Dutch blueprint is passed on to the residents of Karachi for them to adapt and translate it as per their own city’s context.

Mariam Khan is a freelance journalist and a United Nations volunteer. She tweets @mariaamkahn

— Banner and thumbnail illustration by Aisha Nabi