Canal brawl: Does Punjab have a perspective?

With climate stress, shrinking groundwater, storage limits, and neighbourly threats, transparent water management is more critical than ever

Water-sharing disputes between Pakistani provinces are nothing new, so it is no surprise that the provinces of Sindh and Punjab are again engaged in a spat over the recently announced Canals Project, specifically the Cholistan canal, named the Mehfooz Shaheed canal. Although the Water Apportionment Accord (WAA) of 1991, a major legislative act, outlines how the waters of the Indus River will be shared among Pakistan's provinces, the mistrust remains rampant.

Other provinces often claim they are not given their due share, or that Punjab is getting more than its share.

Following large-scale protests in Sindh, the canal project was stopped, linking its execution to the approval of the Council of Common Interests (CCI) after a meeting held between Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif and the Pakistan People’s Party Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari.

Let’s take a look at Punjab’s perspective on the whole issue and if the idea is even realistic.

Green Pakistan Initiative and the need for new canals

Punjab Chief Minister Maryam Nawaz and Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) Asim Munir inaugurated the Green Pakistan Initiative (GPI) in February this year. The GPI is a $3.3 billion project launched by the interim government in 2023, aiming to develop six canals across the country to irrigate 4.8 million acres of barren land, with two located in each of the provinces of Sindh, Balochistan, and Punjab. Five canals are planned to be diverted from the Indus River, and the sixth one will be branched out of the Sutlej River.

The initiative claimed to enhance agricultural productivity and address food security concerns. However, the project has sparked controversy due to concerns over water distribution, potential environmental impacts, and the allocation of water from the Indus River.

A central component of the GPI is the construction of the Cholistan canal in Punjab, designed to irrigate approximately 1.2 million acres of land in Southern Punjab. This canal is planned to draw water from Punjab's existing Sulemanki Bairaj.

Rasul-Qadirabad, Qadirabad-Balloki, and Balloki-Sulemanki link canals were built after the Indus Water Treaty (IWT) to provide water to the areas in Punjab that were previously irrigated by the Ravi and Sutlej Rivers. These three-canal command areas spread over the six districts of Punjab i.e., Bahawalnagar, Bahawalpur, Okara, Pakpattan, Vehari, and Lodhran.

Soon after the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) issued a water availability certificate, clearing the Cholistan Canal Project, Senator Zameer Ghumro filed a petition in the Sindh High Court against it. The approval allowed Punjab to construct the Cholistan Canal branching from the Sutlej River at Sulemanki Headworks, providing access to 450,000 acre-feet of water. Later on, the Sindh High Court (SHC) suspended the certificate of approval of IRSA.

Former Punjab Irrigation Minister Mohsin Leghari told Geo.tv that the Balloki-Sulemanki Link Canal, which once received around 10-12 MAF of water, now gets only about 5-6 MAF.

“So, the people who originally depended on Sutlej River for water have already seen their supply cut in half since the 1960 IWT and they must be most concerned because of this plan, but instead it is our brothers from Sindh, who are protesting.”

He added: “The Article IV of the Indus Waters Treaty clearly states that it is Pakistan’s responsibility to provide an alternative system to those people who, before August 1947, were receiving water from the eastern rivers — Ravi and Sutlej. Pakistan must ensure they continue to get water. This is part of the agreement and is an international commitment on our part. One we have been unable to fully oblige.”

Farmers already on the brink

To continue our exploration on the matter Geo.tv decided to speak to the farmers in the area and get their perspective. Muhammad Saleem, a farmer from Cholistan, expressed his concern regarding the canal project.

“The canals which are already supplying water to Cholistan aren’t even getting required water. If they can’t fulfil the needs of the existing canals, then what’s the point of constructing new ones?

“The farmers here aren’t getting enough water — our crops are drying up, and our livestock are dying of thirst.”

He also shared that they do not even have access to clean drinking water and are forced to drink dirty and bitter water, causing the spread of various diseases.

Meher Ghulam Abbas, President, Anjuman Muzareen Punjab also lodged his objections over the issue.

“First of all, this whole corporate farming setup was introduced during the tenure of the caretaker government, which had no authority to make such long-term decisions.

“The reality today is that it’s already April and we still haven’t received any canal water.”

Abbas said that their crop rotation and water allocation system worked on a calendar. “The canals are closed in December, and water usually returns by the end of the January. We depend on canal irrigation for nine months of the year.”

But this year, he said they (the government) were planning to divert our water to Cholistan. “Now that April is nearly over and we still don’t have canal water, we’re forced to use tube wells for irrigation. “This hardens and depletes the soil, turning fertile land into barren patches gradually.

"The only outcome of this project is that they’ll end up making our fertile lands barren just to cultivate wastelands. They’ve given out blocks of 1,000 acres each on lease — some for 20 years, some for 30.

“And once those leases expire, that land will go back to the control of the Pakistan Army."

Mukhtar Hussain, another farmer from Cholistan, voiced the same concern.

"There is already a shortage of water, and now they want to dig more canals. They can build six, ten, or even 15 canals, but first, they must ensure our water supply."

Tariq Mehmood, a farmer from Bahawalnagar, also stated his reservations.

“Our district is already facing a water shortage. You know very well that the rivers — Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas — were allocated to India under the water treaty.

“That’s why South Punjab, especially the Bahawalpur Division, suffers from water scarcity and to irrigate this region, water is brought in through the Balloki–Sulemanki Link Canal.

He said the water was insufficient to meet their basic needs.

“I have 12 acres of land, but I’m barely able to cultivate 4 to 5 acres because there isn’t enough water for irrigation. The rest of the land lies barren. We can’t even use groundwater because it’s brackish and saline — it damages the soil.”

For the past several years, the canals in the region have faced severe water shortages. The entire Bahawalnagar district receives its water from the Sulemanki Headworks, from where two major canals originate — the Eastern Sadiqia Canal and the Fordwah Canal.

From the Sadiqia Canal, two more canals branch off — the Malik Canal and the Hakra Canal. The Hakra Canal runs along the border and supplies water to Haroonabad and Fort Abbas tehsils.

The Malik Canal supplies water to parts of Tehsil Chishtian and some areas of Bahawalnagar.

“The situation is such that for the past 4–5 years, our canals have been under a system called Warabandi (watering turn)”, Mehmood added.

In normal circumstances, when canals operate routinely, it means all the main canals and their distributaries run continuously — seven days a week without interruption. But Warabandi means that some canals operate for one week and are then shut down the next week. In the following week, a different set of canals is opened, and so on. So effectively, a canal that gets water for irrigation for one week remains closed the next. This means that on any given canal, farmers receive water only once every 15 days.”

Questioning the project’s viability, Mehmood pointed out that the total capacity of the Eastern Sadiqia Canal, which branches off from the Sulemanki Link, is 5,600 cusecs. While the proposed Cholistan Canal has a planned capacity of 4,400 cusecs. That means the water currently being supplied through the Balloki–Sulemanki Link is already insufficient for the Eastern Sadiqia and Fordwah canals. So where will an additional 4,400 cusecs of water come from for the Cholistan Canal?

But Water shortage seems to be only one concern for these farmers, a bigger one is the introduction of a new feudal system in the region. A new class of landlords being created. Large chunks of land — thousands of acres — are being handed over to corporate farming entities. Meanwhile, this land is home to hundreds of thousands of livestock and local communities. People who have lived there for generations raised goats, sheep, and cows, depending on natural rainwater ponds for survival.

If millions of acres of Cholistan land is handed over to corporate farmers, people dread losing access to those natural water reservoirs and mass displacement, and the destruction of entire natural habitat.

Farooq Tariq, General Secretary of the Pakistan Kissan Rabta Committee (PKRC), while talking to Geo.tv endorsed these farmers. He believes that the core issue lies in Pakistan's already severely limited water resources. “Building new canals and trying to cultivate barren lands by cutting down already insufficient water supply is essentially equivalent to turning fertile lands into barren ones,” he stated. The committee is hence opposing the idea and sees no real benefit in this for Punjabi farmers and feels that these canals are being developed for the benefit of the corporate sector.

Canal's water source: A colossal concern

Sindh fears that the construction of these canals, particularly the Cholistan one, will downsize its water share from the Indus River, exacerbating existing water shortages and affecting agricultural activities. In March 2025, the Sindh Assembly passed a resolution opposing the initiative, and protests erupted throughout the province.

Additionally, the Sindh Chamber of Agriculture called for the cancellation of the canal projects, claiming they posed a threat to the federation.

Mohsin Leghari refuted Sindh’s claim that the canal will take water from the Indus. “After the IWT, the water was diverted from the Jhelum River into the Chenab River, from where it flows to Balloki, and from Balloki it is directed to Sulemanki. This is from where they plan to take water for the Cholistan Canal Project. They will not take water from the Indus River.”

“While Sindh fears a potential cut in its water share, it is the people depending on the Sulemanki Barrage who will actually face reduced supplies.”

Naseer Ahmed Memon, a renowned development professional and environmental expert, acknowledged that this is a legitimate concern. He pointed out that only recently, farmers in over 30 cities across Punjab held protests.

“Those raising concerns in Cholistan and Bahawalpur Division — particularly farmers dependent on irrigation from the Sutlej, Jhelum, and Chenab rivers — are right: a serious water crisis is looming.”

He however does not agree that it won’t affect water in Indus by pointing out that, “the entire river system flows downstream from Panjnad towards Sindh, any water extracted upstream will first impact Punjab’s farmers, and then Sindh, and finally Balochistan — because canals supplying Balochistan also originate from Sukkur and Guddu.”

Claims were circulating that this canal project will source floodwater to irrigate Cholistan for corporate farming. The same was recently echoed by Azma Bukhari, while addressing a joint press conference alongside Punjab Agriculture Minister Syed Muhammad Ashiq Bukhari, on April 23, 2025. She stated that the project planned to utilise floodwaters rather than the usual irrigation supply.

Leghari however, refused to buy these floodwater claims. “It is not wise to devise a scheme based on something that is unpredictable especially when you plan to bring corporate investors and make agreements with them. They will demand guarantees for uninterrupted water supply, so when there’s a water shortage, the agreements will get a priority and water will be diverted to fulfill the obligations.”

However, according to, Punjab’s Irrigation Minister Kazim Pirzada, floodwater is often used as a general term and in a misleading way.

“There are three types of canals. Perennial canals operate year-round — though they may undergo brief shutdowns for maintenance. Non-perennial canals operate seasonally. While flood channels only carry water during the monsoon season or when there’s excess water.”

“Each of these receives water based on a separate share and priority level. So when it is claimed that this project will be irrigated using ‘floodwater’, it means the water that becomes available during the rainy season — not literal flooding.”

Even the water availability during a rainy season is unpredictable and a project involving investors cannot be based on that, according to him.

Pirzada, pointed out that, the water for the project would come from within Punjab’s existing share and also highlighted that an alternate water source for the canal would take around 4 to 5 years to complete. “By that time, the Diamer-Basha Dam and Mohmand Dam will also be completed, and then water will be more readily available.”

There seems to be an obvious lack of clarity or deliberate attempt to keep an ambiguity around water source for the canal.

The bottom line

The controversy surrounding the Cholistan Canal Project under the GPI brings to light deeper issues with Pakistan’s water governance framework. With the signing of the 1960 IWT and the 1991 Water Accord, water allocations were formalised, yet persistent shortages and bad political decisions continue to strain this balance.

When the 1991 Water Accord was signed, it was based on an estimated average flow of 114.35 million acre-feet (MAF) of water in the Indus Basin. Under this accord, Punjab was allocated 55.94 MAF, while Sindh received 48.76 MAF, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan were allotted 3.78 and 5.78 respectively.

Following the agreement, IRSA was founded in 1992 to oversee the accord’s implementation and establish guidelines for water distribution on a seasonal basis.

According to clause VI of the 1991 water accord, “the need for storages, wherever feasible on the Indus and other rivers was admitted and recognised by the participants for planned future agricultural developments”.

Leghari lamented that dams weren’t just a suggestion in the accord; they were a lifeline, but we didn't follow through with them, and ultimately successive governments turned water into a weapon.

“Now provinces are fighting over the scraps of what should have been a shared abundance. The storage capacity of the existing dams has also decreased.”

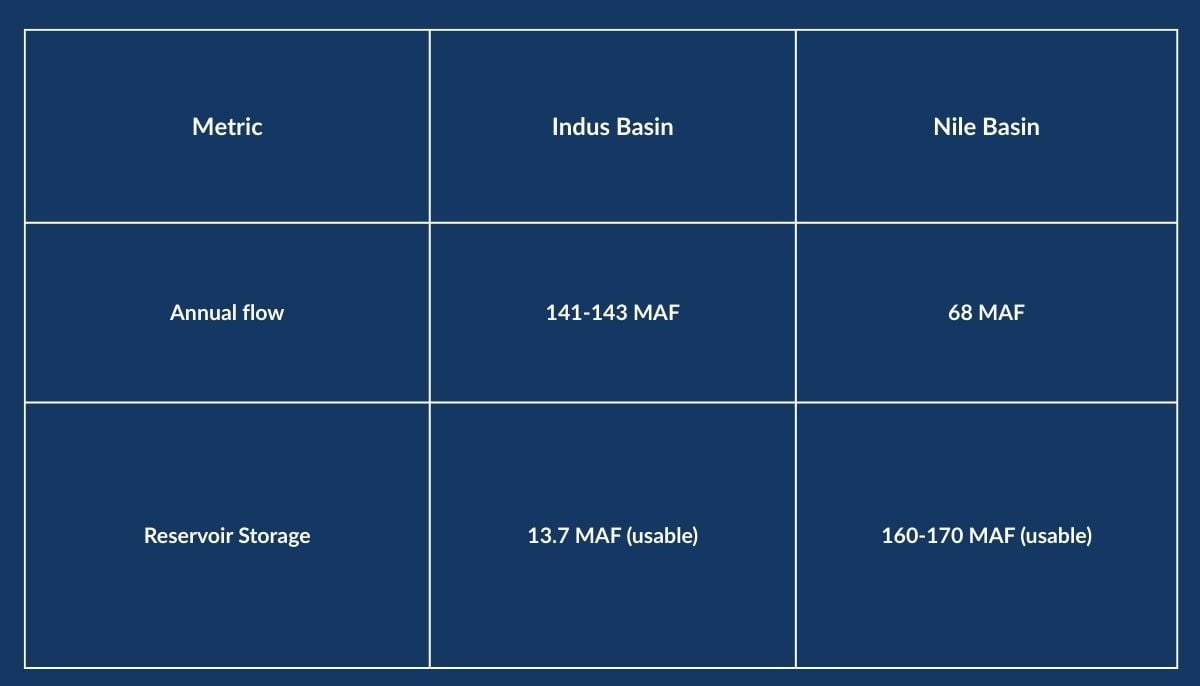

While highlighting Pakistan’s inadequate water storage capacity, Leghari pointed out a critical difference — not only between Pakistan and India but also between Pakistan and the Nile Basin.

“After IWT, India receives about 35–40 MAF of water and has developed a storage capacity of about 18.5 MAF within that volume. We receive 140-145 MAF of water, but our storage capacity is only about 13 MAF. Globally, the average is to store 40% of river flows, whereas Pakistan stores only 9%.”

“The Aswan Dam can store 300% of the Nile’s flow. It can store enough water to last three years, so even if there's no supply during that time, they can rely on the reserves,” Leghari claimed.

Reports and farmer testimonies reveal that both Punjab and Sindh face acute water shortages already. In southern Punjab, existing link canals like Balloki–Sulemanki are already overburdened. Meanwhile, concerns from Sindh — the lower riparian — point to a long-standing fear of losing its already diminished flows. Critics argue that instead of addressing water scarcity and introducing land reform for smallholders, the state is prioritizing large-scale corporate farming that may bypass the local agricultural economy.

Add to that India’s unilateral suspension of the IWT that could potentially jeopardise our entire water resource. The debate is no longer provincial — it is national. As the country faces increasing climate stress, depleting groundwater, limited storage capacity and threats from our neighbour, the need for transparent and sustainable water management has never been crucial. Pakistan must decide now.

Momna Tahir is a staffer at Geo News.

Header and thumbnail image by PPI