At 78, Pakistan is still in the making

Instead of listening to diverse voices within the country, one version of Pakistan — designed by a few — was pushed onto everyone else

Not only must the idea of Pakistan spread to all corners of the country, but it must also emerge from them.

Seventy-eight years on, Pakistanis still can shape the nation’s identity by expanding access to political life, fostering civic inclusion, and committing to the ongoing project of defining Pakistan’s idea.

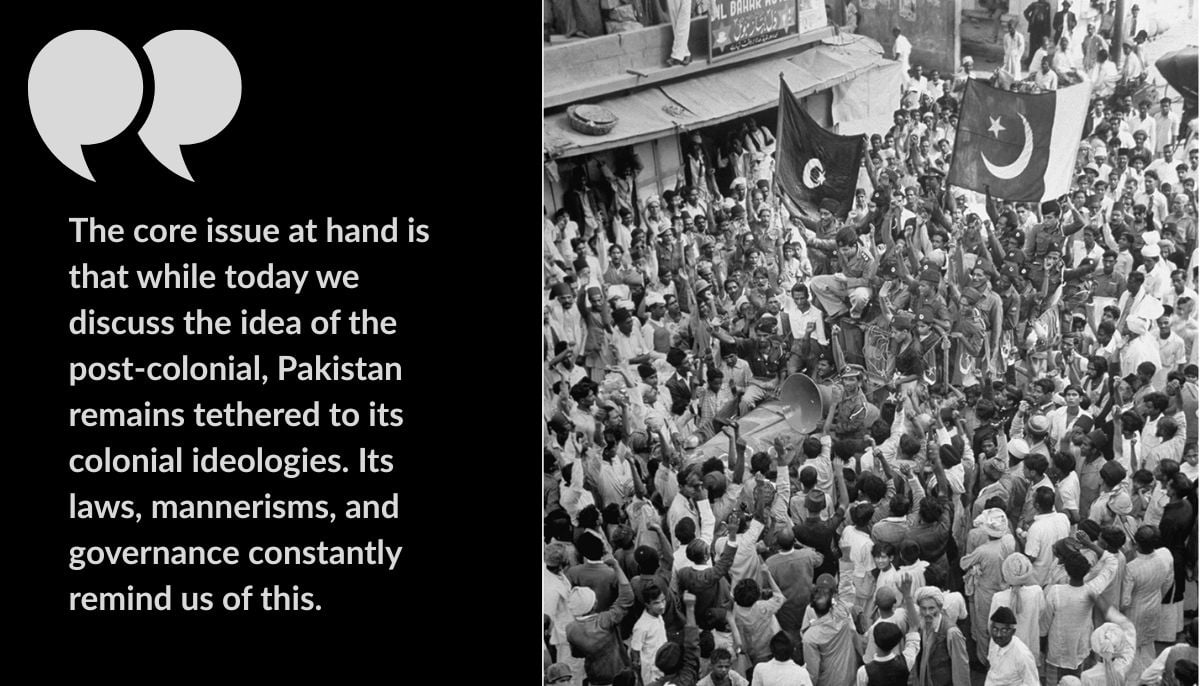

The core issue at hand is that while today we discuss the idea of the post-colonial, Pakistan remains tethered to its colonial ideologies. Its laws, mannerisms, and governance constantly remind us of this. Independence should mean that the Pakistani citizen is allowed to define what Pakistan means for them, and from there we can build onto a more ideal nation state that has let its citizens understand themselves and the polity first and then frames the nation accordingly. In Pakistan, we have missed this step, but the age of the state is still young.

The success of the Pakistani state idea lies in the opportunity that it has been given to merge sometimes radically different cultural codes and ideas. Other nation states, which were allowed to draw their borders, took centuries to develop these, with constant violence and upheavals. Yet Pakistan inherited its borders and its laws, and with them the opportunity to build a nation despite its differences.

The idea of Pakistan was always full of potential. It had the rare chance to bring together people with very different histories, languages, and ways of life—and somehow make it work. Other countries spent centuries fighting wars and drawing borders to become what they are. Pakistan didn’t. It was handed its borders and its laws. And with that, came a real opportunity: to build something new from the ground up. Something inclusive.

But that’s not what happened.

Instead of listening to the many voices within the country, the state tried to push one version of Pakistan, designed by a few, onto everyone else. A ready-made identity, delivered top-down. It wasn’t rooted in people’s lived realities. And that’s the Pakistan we’ve ended up with.

It hasn’t worked. You can see it everywhere now. In how divided we are. In how our economy keeps faltering. In how disconnected people feel, from each other, and from the state. That’s the cost of forcing a narrow vision on a very broad, complicated nation.

We were given a rare chance. We just didn’t know how to use it.

One thing that Pakistan does have aplenty is crises. Luckily, however, crises are a fundamental part of human existence, and they should be seen as an opportunity. A crisis provides a blank slate and creates an opportunity to develop new paths forward. Emerging from crises allows us to shape our collective destiny in a manner that few other modern nation states would allow today, simply for the reason that so much time has elapsed for them. Any change from ‘regular programming’ would radically alter their ideas of the state. In Pakistan, however, time is on our side.

How will the message of Pakistan be spread to all boundaries of Pakistan, if the message of Pakistan does not come from all of its boundaries?

We see today in the rhetoric of ethno-nationalist leaders and politicians from ex-FATA and Balochistan that they belong in the periphery of Pakistan. What is a periphery? A periphery is the outer limit of an area or a secondary position in the spheres of influence.

One could be an economic periphery. The industrialists and the state of Pakistan have heavily invested in what is referred to as KLI—Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. Two of these cities have received more than the third. The majority of Pakistan, however, in Balochistan, former FATA, rural Sindh, South Punjab, and Gilgit-Baltistan have been completely left out of development efforts, or left to the minuscule work of internationally-funded development NGOs. Most funds land in the vaults of corrupt officials.

This has created a sense of disillusionment from the state, where politicians from these areas, particularly from ex-FATA and Balochistan, call themselves members of the periphery, as second-class citizens of Pakistan. For FATA before the FATA merger, this was essentially true.

It is both the job of the state and the politicians to claim that they are not in the periphery, but that they are the land itself.

Resistance as catalyst

However, what does this look like in the present? Pakistan today has taken the role of a manager, someone who applies the rules of business with a manual in hand. Yet a nation is not an enterprise; it is a collective of individuals who deserve to be heard.

In recent years, large-scale policies have been almost entirely extractive. The construction of the (Lloyd) Sukkur Barrage in 1932 led to irrigation in areas that had never had such a high volume of water before. Cities appeared overnight. Raw materials were taken to industries in England, which were now enjoying massive revenue increases, while the farmers who toiled in South Asia got only a fraction of those profits. After independence, landlords close to the British Raj took over.

Fast forward today, these are the same areas facing extreme droughts and left thirsting for water. In the cruellest of ironies, these areas also face massive floods, which have become more common with climate change.

The recent Six Canals fiasco followed a similar pattern, an attempt to irrigate the Cholistan Desert, much like what was done in Sindh a century ago with the Sukkur Barrage. We are poor students of history, even when it stares us in the face. The Indus Delta and all of Sindh were about to be deprived of water. With the extraction of Sindh’s resources complete, Cholistan was to provide a new mirage.

Sindh’s young lawyers and activists rose to the occasion, despite the strongest of capitalists and opponents in front of them, and forced the federal government, which had given a nod to the project, to change course. Despite this recent success, Sindh will be wary of the coming years. In Pakistan’s recent history, this will be seen as a major win for the will of the people.

The colonists managed people. They didn’t see people from other parts of the world as their equals. This is why slavery existed for as long as it did, as an economic ideal of harvesting free manual labour to further build wealth. The Pakistani state today is continuing to act as an extension of a colonial project, but it does not have to be this way.

For this, the state must take the message of Pakistan across. Recent murmurings of abrogating the FATA merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were alarming. It was only in 2018 that the Constitution of Pakistan was enforced in ex-FATA, a region of Pakistan with 6 million inhabitants, that was still being ruled under the colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), a British law that meted out collective punishment to entire towns and villages for the actions of a few individuals. Crimes in FATA weren’t taken to Pakistani courts. Instead, they were settled by local elders, men often swayed by both the state and the powerful forces outside it. Reversing the merger with FATA would have set back the progress made by its citizens in being recognised by the country they were born in. How was this ever supposed to spread the idea of Pakistan across the entire country, right up to the Durand Line, where the border meets Afghanistan?

Peace marches against terrorism, where thousands from across ex-FATA showed up, have, for now, silenced these murmurings. The federal government was once again forced to state that FATA would not be brought back under exclusive federal control but instead would be allowed to be managed by the province, as is the rest of Pakistan.

One thing is remarkable about both these examples. Sindh has some of the most underdeveloped areas of the country, and ex-FATA has only recently joined the federation. Yet the largest resistance, which in reality should only be seen as a will to better the state, has come from these territories.

Language and erasure

Then we come to our students. Education of language in schools remains a contested debate in Pakistan, though it seems that the state has already decided. While Urdu has been the applied language for a unified territory, Pakistanis know that Urdu is not the first (and in several cases, not even the second) language spoken by them. Yet, instead of tailoring education to regional languages, teachers are forced to teach in Urdu or English, and students are forced to learn in Urdu or English.

Teachers and students often switch to local languages to make sense of things. But when exams are only in Urdu or English, it holds students back. It limits what they can really show or do. Language has been used as a tool to shape national identity in Pakistan, but it has also been a source of deep conflict and resistance. Pakistan, however, made a grave mistake by adopting an official language barely spoken by most of its inhabitants.

One might think that this issue is only for languages that have few students, but bear in mind that even in the language spoken by the majority in Pakistan, Punjabi, students have been reprimanded for speaking in the language that they speak at home and are most comfortable in. Urdu is by all measures still a very new language for the Subcontinent, yet as part of its nation-building project, the Pakistani emphasis on Urdu has led to the erasure of regional languages being used as projected as an intellectual strength of the nation. English has had the same devastating consequences.

At 78, the idea of Pakistan must come from the entire Pakistan. A forced Pakistan will always face resistance, but that is also its greatest strength.

Saeed Husain is an anthropologist and editor at a publication house. He posts on X @saeedhusain72 and can also be reached at [email protected]

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv