Unearthing the foundations of a land scam — and the rot beneath

In major urban centres across Pakistan, conventional 30% rule applied for housing costs is clearly beyond threshold

Pakistan’s real estate sector has long been portrayed as a tale of two plans by architects and planners. On one hand are the so-called master plans, prepared and ignored over the years, and on the other are the speculative plans that spur de facto growth via planned informality.

Amid this dichotomy reside the indigenous communities on city peripheries and the urban poor in various localities, whose existence is frequently questioned due to information gaps in formal plans. This often results in the systemic erasure of their identities and the threat of sudden, forced evictions to make way for high-rise buildings or shiny gated communities. Their mere presence in the undocumented gap is then weaponised against their existence under the labels of encroacher or "terrorist."

Historical context of land ownership

Countless stories tell us of this schism. Amma Hajran's is one of them. Her story brings the biblical epic of David and Goliath to mind. She stood tall against the goons of a real estate giant who harassed the communities living along the Mol Naddi in District Malir. In a recorded video interview, she discusses the existence of her community for more than 100 years in this area. This knowledge gives her the strength to stand against the real estate tycoon.

Many villages surround the Mol-Mandhiaro streams in Gadap. Several have been erased in the quest for real estate projects since 1993, when the Sindh government established the Malir Development Authority (MDA). The purpose was to oversee development, improve socio-economic conditions, formulate development schemes, acquire land, and exercise local government functions within its designated area.

Before this formalisation, land in Gadap was distributed to those interested in developing it for agricultural purposes. Much of this land is barani (rain-dependent), and the local population cultivated it for seasonal vegetables, fruits, and fodder. This land was also assigned to interested outsiders on katcha kaghaz (informal document) by the revenue department patwaris, a legacy of the colonial era. This katcha kaghaz was just a handwritten, unofficial record, which made the owner highly vulnerable to being challenged in court or simply ignored by official bodies. It also enabled the patwari to exploit the so-called owner of the land.

Cultivation of this land was further complicated by the intimidation tactics of local feudal landlords. Moreover, as rain became scarce and the groundwater table declined because of illegal sand and gravel mining, many local caretakers were forced to migrate to urban areas. Many of these migrants joined the ranks of the urban poor.

Planned informality and the fractured city

The cities, too, are poorly planned, and the migrants coming in from the peripheries and rural areas have no choice but to live in informal and undocumented zones. Thus, they live on the fringes, both physically and financially. While they are dispossessed of their communal meadows and small farmland systemically, not just because of migration, but also because of a lack of clear title documentation, they also risk getting evicted from informal settlements at a moment's notice. A stark illustration of this is the OPP-RTI research, which shows that of the 2,173 villages in Karachi's peripheral towns, over 1,100 have already become urban settlements.

According to Ibrahim Amin, chairman of TriStar International, poor city planning and unclear land ownership have led to uncontrolled growth and pushed many into informal settlements. “About 40% (urban researchers put the number at 60%) of urban residents live in these areas. The government needs to improve land records, give legal ownership to residents where possible, follow city master plans, and allow more high-density housing near public transport.”

However, the government has failed to address this foundational issue, making community-led initiatives, such as Perween Rehman’s counter-mapping of waterways, stormwater drains, natural causeways, and infrastructure, a critical undertaking by the Orangi Pilot Project.

The mapping of Chhota Maidan Colony by the slain activist provided a critical counter-narrative to Rehman plans by documenting the existing infrastructure and communities. It brought into focus the concept of planned informality, a deliberate process that has created a fractured city, often invisible in macroeconomic indicators.

Karachi is a city fractured in multiple ways, with divisions often overlapping. A sharp socioeconomic gap exists in infrastructure accessibility between low-income areas or katchi abadies and more affluent neighbourhoods. This is further compounded by ethnic divisions, particularly visible in areas like Lyari and Orangi.

Political and administrative differences are prominent when comparing cantonment areas with non-cantonment ones, which often leads to a disparity in services and development. Physical and geographical divisions also exist, separating the city’s peripheries from its centre, and are exacerbated by features like the Gujjar and Orangi nullahs. Finally, cultural and ideological fracturing is seen in the marginalised living conditions of minority groups within the city.

These overlapping layers of division create deep divides and pervasive inequality, revealing how planned informality and speculation consistently price the poor and middle-income out of a basic human right: a place to call home.

The power structure of land speculation

Within the market economy, housing is a commodity which has three broadly categorised stakeholders – beneficiaries, affectees, and facilitators. The beneficiaries include investors, builders, developers, and people belonging to housing finance organisations, professionals, contractors, architects, and planners. Affectees are the urban and rural poor, agricultural workforce, livestock farmers, indigenous communities, and initial owners and occupants. Whereas the facilitators are various government agencies, regulatory bodies, politicians, and law enforcement agencies that carve out land to supply for real estate.

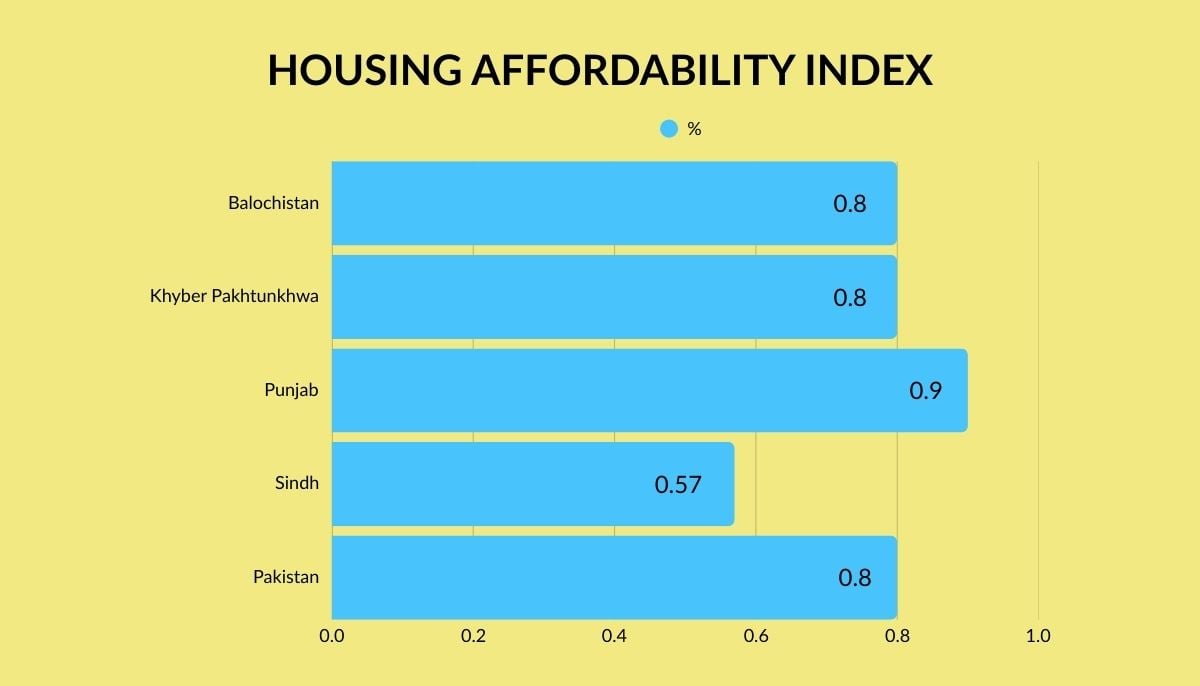

The severe affordability crisis is an outcome of this power structure. Musab Iqbal, Vice President REIT at JS Investments, shared the latest data, including the national Housing Affordability Index of 0.83 and Sindh’s 0.57 (Table 1), which demonstrates that even middle-income families face unsustainable mortgage burdens. He explains, “Large-scale luxury housing developments, while contributing to overall construction activity, fail to address the affordability crisis confronting low- and middle-income households.”

Luxury projects that target high-net-worth buyers and investors, insulated from affordability constraints, do not deliver units at price points accessible to the majority. “Moreover, such developments consume scarce serviced land and urban infrastructure capacity that could otherwise support mid-income or affordable housing projects,” Iqbal said.

“Without policy interventions such as inclusionary and opportunity zoning, density bonuses for affordable units, or targeted financing incentives, luxury projects risk exacerbating the affordability gap rather than narrowing it,” the REIT expert explained.

An HBFC report from November puts the national house price-to-income ratio at 5.06, or over five times the median household income, pointing to a severe affordability challenge. For Sindh, this ratio is the least affordable at 8.85, particularly driven by urban centres like Karachi. Punjab's ratio, though comparatively lower at 5.74, is still slightly higher than the national average, while Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's ratio is at 3.94, or over three times the median household income. Thus, in major urban centres across Pakistan, the conventional 30% rule applied for housing costs is clearly beyond the threshold.

To top it off, real income growth has lagged far behind the surge in housing prices, particularly during high inflation and economic instability. So even if nominal incomes increased for some people, their asset purchasing power remained compromised because of stagnant real incomes. This also tells us of low or poor savings capacity. HBFC data shows that in Sindh, a median-income earner would need to save 2.65 years of their entire income to afford a minimum 30% down payment on a house.

Investors and speculators make the affordability crisis even direr because of high inflation and currency devaluation.

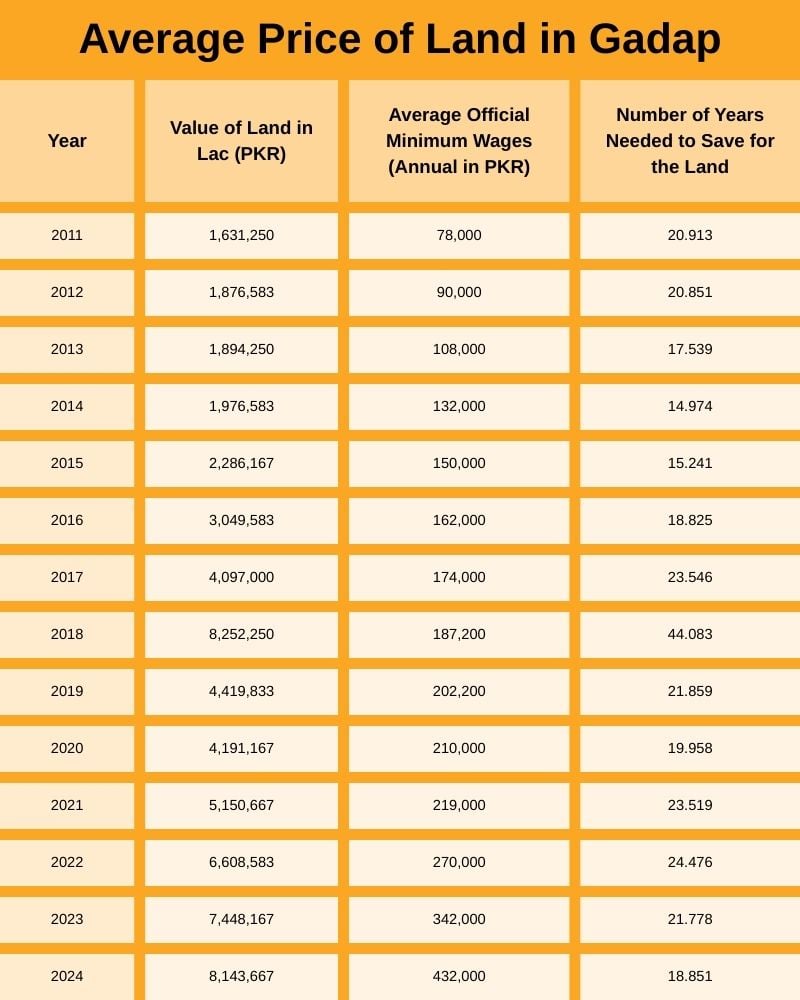

Land speculation as a hedge against devaluation

The percentage increase in the exchange rate from 1981-82 to 2023-24 is approximately 2,836.88%. In the absence of robust investment avenues and de-industrialisation (overall decline in manufacturing and employment capacities), people have turned to land ownership to not only preserve their wealth, but also for growth. In the recent decade, the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) diktat to abandon all control over the rupee, with the declaration of the construction sector as an industry, further impacted the real estate market. (Table 2)

Exchange rates for mark-to-market revaluation - History (SBP)

Amin said, “The free-floating exchange rate helped the economy adjust, but made building costs unstable, pushing people to invest in real estate as a safe option. The 2020 construction package boosted activity but also led to more speculation in unregulated areas. Future policies should be clear, limited in time, and linked to actual delivery of affordable homes.”

This brings into sharp focus the story narrated by Muhammad*, who bought a Rs5.2 million two-bedroom-lounge, less than 650 square-feet apartment in Karachi in 2019. After waiting 1.5 years for possession, and another couple of months for finishing works, he rented the apartment to a tenant at Rs20,000/month. In December 2024, he sold the apartment for Rs9.2 million. He said that he earned a huge profit, but still it wasn't enough for him to buy a comfortably sized two-bedroom, drawing-dining apartment.

In rupee terms, his profit jumped 77%; however, in dollar terms, and after adjusting for rental income, his profit clocked in at 2.74% in real terms. This happened because the rupee lost 88% of its value between the time he bought the apartment and when he sold it.

According to the TriStar chairman, in major cities, property prices compared to household income are very high. Rental yields are low, averaging only about 5 to 6%. This means that property values are rising more because of speculation and as a hedge against inflation, rather than due to real rental income. Over the last ten years, property prices have grown much faster than people’s incomes, especially in high-inflation years.

While Muhammad’s case highlights the investor’s dilemma, Farah’s* story illustrates the affordability struggles of a middle-income end user.

Farah*, who has been saving for years and has bought two small apartments, plans to sell both apartments and add additional savings to buy a house. But every time she goes house-hunting, she faces multiple hitches, the most prominent being the price of even an 80-yard house in Bufferzone, Karachi. “My father bought a 250-yard house in the good old ‘60s in Nazimabad when he was hardly 45 years old. I have been toiling since the age of 22, but I cannot yet buy myself a high-value land, let alone a high-value house. What’s 80 yards?" she asks.

Muhammad* and Farah* did not seek out banks to buy their properties, a point reiterated by Amin, who said, “Very few people buy homes through mortgages, and most purchases are paid in cash.”

Speaking of the attractive projects, he said that a large part of the market invested in the Defence Housing Authority and Bahria Town. “In big cities, about 40 to 60% of sales for plots and new apartments are made by investors, not people who plan to live in them. This number goes up when the currency is unstable,” he added, explaining not only the lower number of end-users in the market, but also the connected affordability crisis, as prices are further pushed up because of speculators and investors seeking out property as a hedge against inflation.

“Because of high inflation and repeated drops in the value of the rupee, people and businesses now see urban land and prime property as a safe way to protect their money. The change to a free-floating exchange rate made imported construction materials more expensive and unpredictable. As a result, real estate in big cities is now used more to protect wealth than to provide housing, especially since mortgage options are minimal,” Amin stated.

REIT as a solution

While informality, speculation, and volatility remain major concerns in Pakistan’s real estate sector, some experts hope that a better-regulated environment under Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) could help address affordable housing.

Both Iqbal and Amin are on the same page about REITs and urge the government to provide the necessary structural support and policy.

JS Investments’ Iqbal said, “Affordable housing REITs could focus on developing mid-income rental units, mixed-income projects where higher-end components subsidise affordable stock, or public-private partnerships where government contributes land at concessional rates.”

“To make these financially viable, critical enablers would include the revival of Section 99A to restore tax efficiency, provision of density bonuses or fee waivers for affordable components, and targeted credit enhancements such as partial risk guarantees for rental income streams.

“By aggregating capital from institutional investors and deploying it into professionally managed, income-generating affordable housing portfolios, REITs have the potential to significantly help bridge the supply gap for low- and middle-income households while offering steady, inflation-hedged returns to investors,” Iqbal said.

However, social justice activists only see this as the corporatisation of land. They argue that REITs reinforce the view of housing as a financial commodity for investment rather than a human right. Thus, they say that REITs encourage financialisation, where real estate is separated from its social purpose of housing and used for wealth extraction, potentially at the expense of tenants and low-income residents.

In Pakistan, where the housing crisis is already acute, the financialisation of housing, supported by a market-oriented legal and policy framework to attract investment, including from corporate landlords and equity funds, would particularly exacerbate the affordability gap and lead to more evictions and homelessness.

What is needed is a socially motivated policy, which is formulated with a deep focus on ground realities connected to the housing affordability crisis. The rise of land prices in areas like Gadap, for example, illustrates this crisis (Table 3).

If 80% of the price of an urban house is attributable to the cost of land and its acquisition, further financialisation would devastate the poor.

Andaleeb Rizvi is a journalist and a former staffer at The News. She has editorial expertise on Pakistan’s economy, trade, and urban development, with academic experience in architecture and planning.

Header and thumbnail image by Geo.tv