Thirteen years after Baldia blaze, families remain on trial by fire

Over a decade after Baldia inferno, fundamental problems persist as similar incidents claim innocent lives of working-class labourers

Today marks the 13th anniversary of the Baldia factory fire in which 260 people were killed and dozens were injured. Every year since 2012, the families of these victims have converged on September 11 outside the blemished structure of the local production facility that once provided garments to foreign brands, only to reiterate their demands for decent working conditions, health, and safety that have fallen on deaf ears among policymakers and implementers since this incident. Although their gathering won't take place due to unforeseen circumstances this year, they echo the same demands.

"Nothing has changed," remarks Husna Khatoon, a woman in her 40s who lost her husband in the blaze and is the current president of the Ali Enterprises Factory Fire Affectees Association (AEFFAA). “We have been making speeches, holding rallies, and demonstrations to demand justice not just for us but for the entire workforce so that no one should meet the fate that we and our loved ones did, but it appears to cause little to zero impact.”

Instead, their problems continue to rise. Husna explains that the parents of those who died in the factory fire now require medicine more than food, but their compensation payments have been stopped, leaving them vulnerable to food insecurity and health complications.

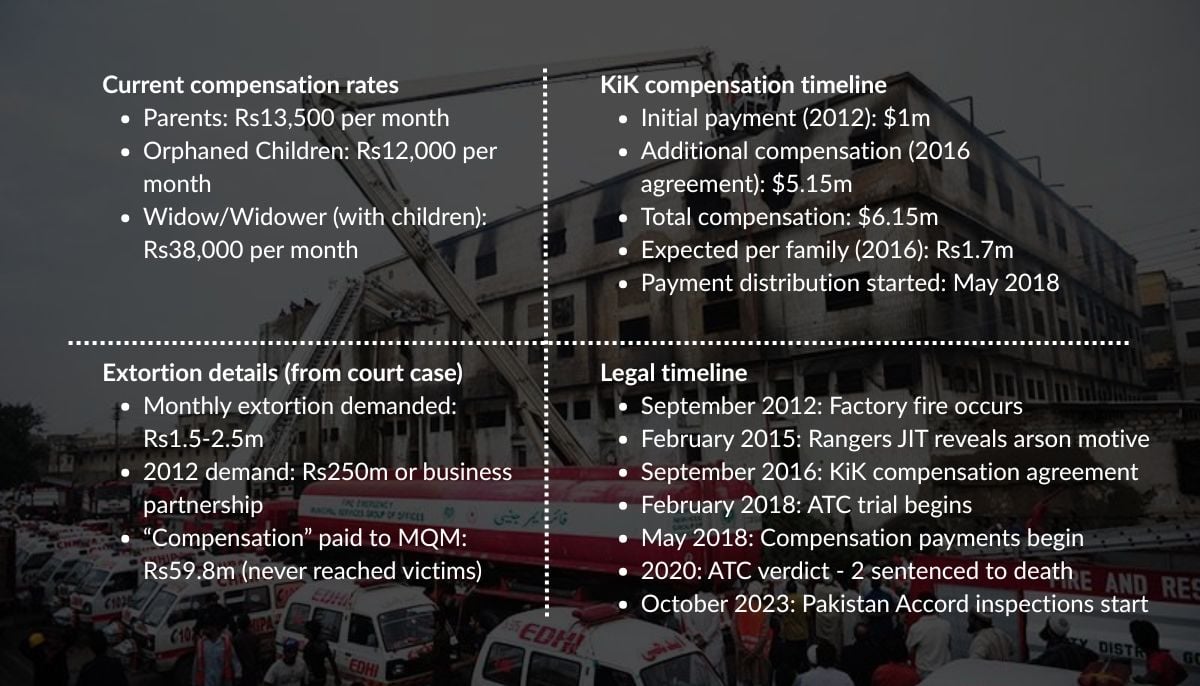

Currently, the victims receive compensation according to the following rates: parents get Rs13,500, orphaned children Rs12,000, and widows or widowers including children Rs38,000.

Compensation: A trial by fire

What was meant to provide relief has become another source of frustration for the families. Since 2014, a case regarding group insurance for victim workers has been pending. “We don’t have clarity on how our $5.15 million compensation is being distributed,” Husna said, referring to the landmark 2016 agreement where German retailer KiK, which sourced over 70% of the factory’s production, agreed to pay compensation through the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

The families now face a troubling issue: their compensation money has been allegedly invested with a private insurance company without their consent, and the details of this agreement have not been shared with them.

The compensation arrangement was initially hailed as successful. In 2018, the ILO announced that beneficiaries had “conveyed their satisfaction with the process” and called it a precedent for protecting Pakistani workers. Seven years later, those same families are raising concerns about transparency and consent regarding their compensation funds.

According to Nasir Mansoor, general secretary of the National Trade Union Federation (NTUF), the ILO made this investment decision unilaterally. The ILO is reluctant to share details of the agreement with victims and wants non-disclosure agreements signed so details cannot be shared with anyone. This is a very dangerous characteristic of the ILO,” Mansoor said.

Geo.tv reached out to ILO for comments, but received no response from the organisation by the time of publication.

Meanwhile, factory owners appealed the compensation commissioner’s decision at the Sindh High Court, though the court referred the matter back with instructions to hear all parties. Another pending issue is workers’ gratuity payments. “This is all in violation of the SHC order that gives the victims’ families compensation for a lifetime,” Mansoor added.

The power game that traps workers

The power imbalance that keeps Pakistani textile workers trapped in poor conditions isn’t just about local corruption or weak laws; it’s built into the global system itself. In Pakistan’s textile industry, a handful of international buyers control orders worth billions, while thousands of local suppliers compete desperately for contracts.

“Already the brands offer minimum rates for production and in this cut-throat competition, it is impossible for an SME to ensure everything,” explains Syed Nazar Ali, general secretary of the Employers Federation of Pakistan. When margins are razor-thin and buyers can easily shift orders to Bangladesh or India, workplace safety becomes the first cost to cut.

This creates a vicious cycle. Factory owners know that investing in proper fire exits, electrical safety, or worker training will increase costs and potentially cost them contracts. So, they cut corners, bribe inspectors, and hope nothing goes wrong.

The AEFFA president commented that factory owners don’t care about their workers, oblivious to the fact that the money they use to live lavish lives comes from the labour of workers who they treat as disposable resources. “If there were no workers, they would not be owners.”

International frameworks, local gaps

The Pakistan Accord on Health and Safety attempts to address these systemic issues. According to Country Director Zulfiqar Shah, the agreement between international clothing brands and global unions currently has over 130 signatory brands, including Adidas Group, Levi Strauss & Co, H&M, Hugo Boss, and others. These brands collectively source goods worth over USD4 billion annually from Pakistan, with more than 600 factories covered under the programme.

The Pakistan Accord started formal inspections in October 2023. Up to September 5, 2025, over 270 factories have been inspected for fire safety, building safety, and electrical safety. The programme has trained 100,000 workers from 90 factories and received over 150 complaints.

However, Shah acknowledges significant limitations. Regarding recent fires in Karachi’s Export Processing Zone, he said none of those factories produce for signatory brands, so they were not covered. “Our direct relationship and intervention are limited to the listed factories that produce for signatory brands.”

Mansoor believes the accord needs expansion beyond health and safety to cover freedom of association and sexual harassment and wants Pakistan represented on the International Accord’s steering committee. The accord was "an outcome of a struggle spanning 10 years", and he wants its tenure extended.

Systemic enforcement failures

The gap between policy and practice becomes stark when examining government oversight. Gulfam Nabi Memon, former joint director of the Sindh labour department, said factories don’t comply with health and safety rules "to save money".

Fire and other workplace hazards continue because the labour department doesn’t perform its duties correctly, and there is corruption among labour inspectors. Workers are also not trained to know their rights or how to deal with dangerous situations. When factories are registered, no proper checking mechanism ensures they follow safety protocols.

“Most of the time they don’t go inside the factory,” Memon said about labour inspectors, adding that while previously owners would offer them tea and cash, now "they are handed over envelopes at the gate". By law, factories need to be checked by labour inspectors at least once a year. While fines increased after the 18th Amendment and now range from Rs10,000 to Rs100,000, "the biggest issue is corruption", he added.

The 70% problem

The statistics are sobering. Karachi Chief Fire Officer Humayun Khan revealed that in 70% of fire incidents, short circuit is the reason, meaning electrical safety is a major concern. "When a fire starts, other factors such as dust and flammable materials increase it."

Karachi currently has 29 fire stations for its massive population. "As per international standards, one fire station is needed for a population of 100,000," Khan said.

Official documents from the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation Fire Brigade Department reveal the scope of these challenges. The city’s 30 fire stations are equipped with 43 newer fire tenders and 19 older vehicles still in service, with several marked 'under repair' or out of service due to accidents. This gives Karachi roughly 62 operational fire vehicles for a population exceeding 20 million people.

The fire department previously had the mandate to check buildings for fire safety, but this power has been taken away. While the Sindh Building Control Authority should consult with the fire department when issuing NOCs (no-objection certificates), “this does not happen", Khan added, crediting Karachi Mayor Murtaza Wahab for providing support to the fire department in these difficult times.

This creates dangerous situations where firefighters don’t know building layouts, making it difficult to contain fires. Due to these challenges, 34 firefighters have lost their lives in rescue operations. The department is also severely understaffed, with the last appointments made in 2009.

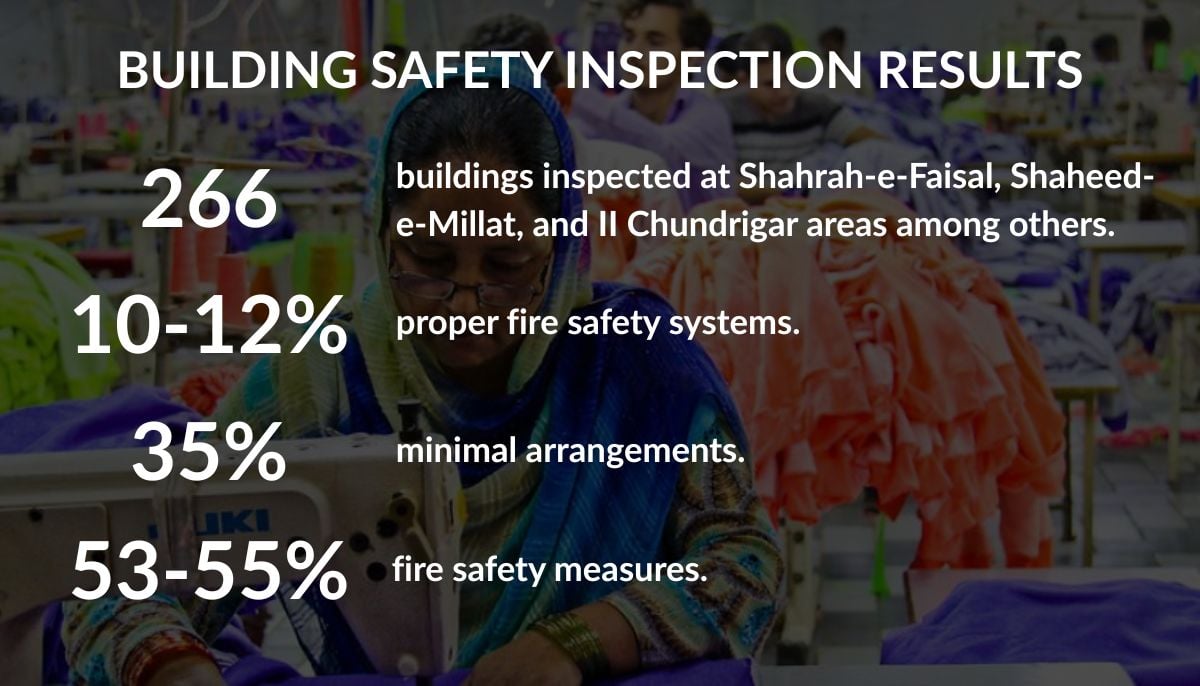

After an office building fire on Shahrah-e-Faisal, 266 buildings were inspected for fire safety. Only 10-12% had proper fire prevention and fighting mechanisms, 35% had minimal arrangements, and the rest had nothing.

The arson verdict's shadow

The case took a dramatic turn in 2020 when an Anti-Terrorism Court found that the fire was not an accident but arson by MQM extortionists. Two MQM workers were sentenced to death after the court determined they set the factory ablaze because the owners refused to pay Rs250 million in extortion.

However, victims' families remain unsatisfied. "We deemed the factory owners responsible for the mayhem,” had said the then AEFFA chairperson Saeeda Khatoon, who had lost her 18-year-old son in the fire. Saeeda died in 2022. Mansoor called it a "moth-eaten verdict" where "only the lower tier of perpetrators was granted punishment" while factory owners "were given a clean chit".

The continuing pattern

Thirteen years after Baldia, the fundamental problems persist. Recent incidents like the Landhi export processing zone, firecracker warehouse explosion, and the September 9 New Karachi factory fire show the deadly pattern continues. In most cases, short circuit remains the cited cause, highlighting that electrical safety challenges have not been addressed.

The AEFFAA and NTUF, in collaboration with international partners, continue campaigning for justice. But as Husna reflects on their annual gathering outside the burnt factory shell, the message remains unchanged.

While international frameworks like the Pakistan Accord and trade incentives like GSP+ promise improvements, the benefits continue flowing upward to factory owners and international brands. Workers remain at the bottom of what researchers call the “exploitation curve,” trapped between global economic pressures and local enforcement failures.

As Pakistan’s textile industry continues to be central to the economy, contributing 8.5% to GDP and employing 15 million people, the Baldia tragedy serves as a stark reminder that without fundamental changes in how workplace safety is prioritised and enforced, more families may join Husna’s years-long pain tied to such factory walls that have become monuments to preventable deaths.

Zubair Ashraf is a journalist. He posts on X @zubairrashraf

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv