The dry truth: Inside Karachi's failing water system

Water is a basic necessity, yet millions in Karachi, despite paying their bills, face chronic shortages each day, forcing them to spend on costly tankers or turn to unsafe sources just to meet their most essential need.

This crisis has deep roots in ageing infrastructure, corruption, and mismanagement.

Some areas of Karachi receive water at regular intervals, but in most parts, residents have not seen water flow from their taps for years. One such neighbourhood is Bostan Rafi Malir, located on Jamia Millia Road and part of the Town Municipal Corporation Model Colony.

Residents say they have not had water from their taps for a decade. This formal settlement has pipelines laid, and water bills come regularly, yet no water flows, causing the pipelines to fall into disrepair. In many adjacent areas of Shah Faisal Colony, water arrives for only one or two hours every three days. Most settlements in Karachi have not seen water for six months or more.

The Karachi Water and Sewerage Corporation (KWSC) is responsible for supplying water across the city, but many residents remain without regular access.

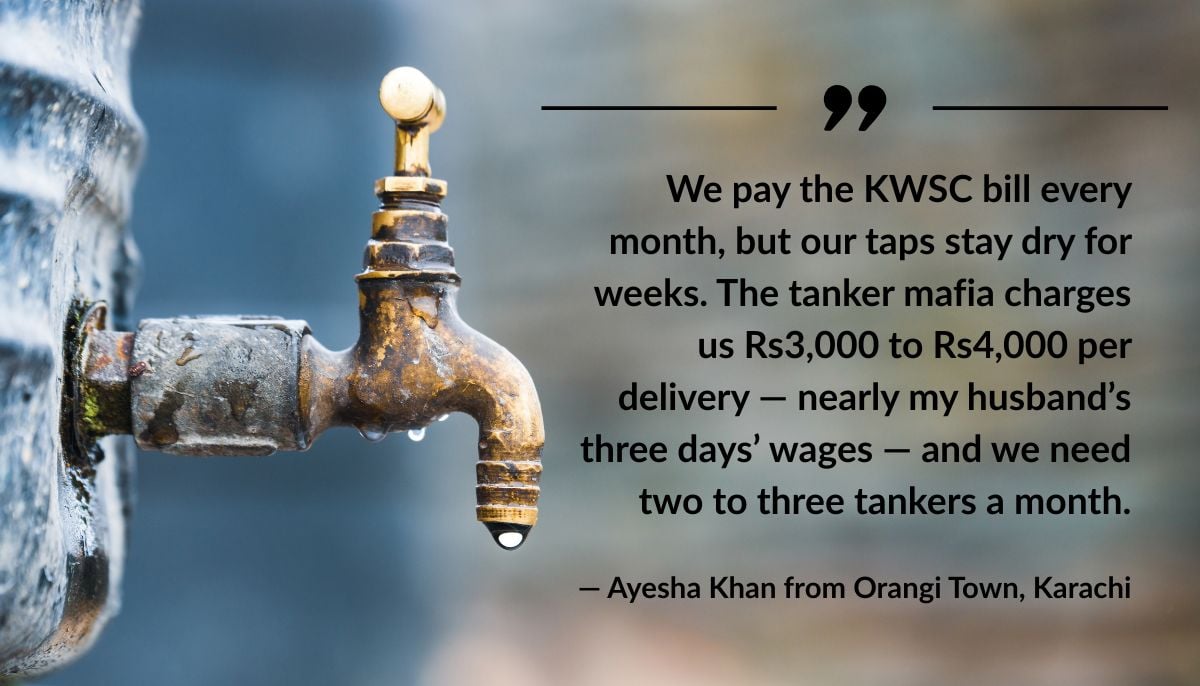

"We pay the KWSC bill every month, but our taps stay dry for weeks. The tanker mafia charges us Rs3,000 to Rs4,000 per delivery — nearly my husband’s three days’ wages — and we need two to three tankers a month," says Ayesha Khan, a mother of three in Orangi Town.

Karachi residents face a cruel paradox: they pay monthly bills for piped water that rarely arrives, while spending thousands on private tankers to meet daily needs. If they do not pay KWSC, the agency refuses to clean and repair sewage and drains during overflows, turning streets into filthy canals.

Experts say a nexus between corrupt KWSC officials, and the tanker mafia benefits from the city’s unregulated supply. With 70% of Karachi’s population reliant on tankers, this crisis has become a profitable business, forcing citizens to pay multiple times for basic water rights.

Such unequal distribution is unheard of in any civilised society. In Karachi, however, the law of the jungle prevails. The city’s water institution — Karachi Water and Sewerage Corporation (KWSC) — admits it cannot provide water to all residents but does not reveal that its employees have allegedly raked in billions from this unequal distribution. The agency claims it initiated hydrant and tanker chains to supply remote areas, which then grew into a network of legal and illegal operations, sparking debates over which hydrants are ‘legal’ and which are not.

With no water available for years, people resort to self-sufficiency. Many drill boreholes up to 120 metres (400 feet) deep at a cost of Rs600,000, shared collectively by 3 to 4 families because no middle-income household can afford this alone. Those who cannot afford boreholes pool money to buy tankers. Often, potable water is mixed with brackish water to meet needs.

Many families buy drinking water from small filtration plants that sell it for Rs1 a litre. These plants, approved by the Karachi commissioner’s office and set up as charity projects, stand close to KWSC pumping stations. Those who cannot afford even this price wait in long lines at public taps, known as Awami Nalkas, to fill their containers for free. At the same time, private vendors draw water from these taps and sell it door to door for Rs3 a litre, adding more if they must carry it to upper floors.

Al-Khidmat Foundation is the only charity running more than 55 reverse osmosis (RO) plants in Karachi. It sells lab-tested water for Rs1 a litre. Alongside, thousands of private RO plants sell water for Rs2 to 3 a litre without any quality checks.

Millions of middle-class families still wait for water from the KWSC supply. Some order tankers through the KWSC app, while others turn to private tanker services. A resident said tankers booked on the app can take almost a week to arrive. Private tankers reach within hours but charge nearly three times as much.

It’s often the very same tanker and the very same driver doing both jobs. Instead of reaching the city’s pipes, much of the water is quietly diverted into those tankers and sold for a hefty price. For the poorest, it’s simply out of reach. Long after dark you’ll see women and children waiting at the public taps, plastic cans in hand, hoping to fill enough for the next day. Some stay there till dawn.

The daily fight for water is taking a heavy toll on people’s mental health. Neighbours argue, families clash and KWSC staff face constant verbal abuse. In many slums, it is children who carry the burden of fetching water. They often miss school to queue at public taps, and many drop out altogether. The 2023 census counts 5.6 million children aged five to sixteen in Karachi; 1.8 million are already out of school, and nearly two-thirds of them live in slums. The shortage also means women cannot keep up with basic housework, while men are forced to skip work.

The KWSC app, which claims to serve thousands, fails on the ground. Users report being blocked from requesting tankers for days, a tactic to limit ‘overuse’ but effectively forcing desperate families to buy expensive private tankers. “I tried to book a tanker but was blocked for six days. Meanwhile, my children drank unsafe water,” said Ali Gul, a construction worker from Malir. KWSC officials call this a technical glitch, but it reflects deeper governance failures.

Meanwhile, new water theft methods are emerging — thanks to our juggard mentality. The recent bursting of an 84-inch pipeline at Karachi University is linked to illegal connections. KWSC linemen and valve men reportedly extort money to open taps, control water distribution, and arrange illegal connections. Political figures and city councillors also profit by promising water supply, often without documentation. Despite millions spent daily by citizens, no revenue reaches the government treasury.

Water access in Karachi no longer comes with dignity. The agency meant to provide safe water is involved in illegal, costly supply schemes, with employees and private actors colluding for profit. Despite 17 years passing, KWSC has added no new water to Karachi’s supply, while population growth surges. The long-delayed K-IV project, promised to deliver an additional million gallons per day (MGD), remains incomplete past mid-2025 amid delays and corruption allegations. Even if completed, it will fail to meet the city’s growing demand.

Commenting on the K-IV project, Farah Ishtiaq, a teacher and resident of Shireen Jinnah Colony, says, "We’ve heard promises of running water for years, but nothing changes. Our children have grown up believing water comes from tankers, not taps."

According to Abdul Qadir, a spokesperson for KWSC, despite limited resources, the corporation is striving to supply clean and quality water to every area, institution and individual of the city and to make the sewage system more functional.

Dismissing supply gaps, Qadir claimed there was no part of the city without water service, though some neighbourhoods receive it only on alternate days and for limited hours.

Terming the K-IV project a lifeline for Karachi, the KWSC spokesperson said that after operationalisation, it would significantly reduce the city’s water crisis.

Karachi faces a compounded crisis from climate change, institutional corruption, unfair distribution, and a powerful tanker mafia. The real question is not when the water crisis will end, but who will challenge the entrenched mafia and break the cycle.

Fair water distribution is essential. This requires full documentation of the system and accountability from KWSC linemen to top officials. A transparent, efficient supply is impossible without eliminating hydrants and tankers. Public participation is crucial; KWSC should share project costs, timelines, and plans openly, listening to citizens’ concerns. A civil society board could oversee this process.

Muhammad Toheed is an urban planner, geographer and Associate Director at Karachi Urban Lab, IBA. He posts on X @UrbanPlannerNED

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv