Struggling with the pull of suicide? Let's talk about it

Uroosa* continues her day with daily household chores as she watches her two children play in the corridor on a rainy September afternoon. While it may appear to be an ordinary household scene, for Uroosa, every laugh of her children serves as a reminder to be grateful for a life she once tried to end. “I thought it was the only solution,” she recalls softly. “I couldn’t handle the burden anymore, the children, the house, the in-laws, and the stress. It all became too much.”

A 33-year-old housewife in Karachi sat down to speak for the first time about the most traumatising chapter of her life.

Marking the occasion of World Suicide Prevention month, the mother of two hopes to spark a conversation about suicide, one that moves the focus from stigma to understanding and support.

Recalling the painful emotions that pushed her toward a suicide attempt, Uroosa, who has been married for 10 years, speaks of her early struggles with mental stress, which were right after the birth of her second child, just months after the first. What seemed like joy quickly turned into exhaustion and resentment as sleepless nights, distant family responses, and the crushing weight of domestic responsibilities pushed her deeper into postpartum depression. “At that time, the only thought on my mind was that committing suicide was the final solution,” she said.

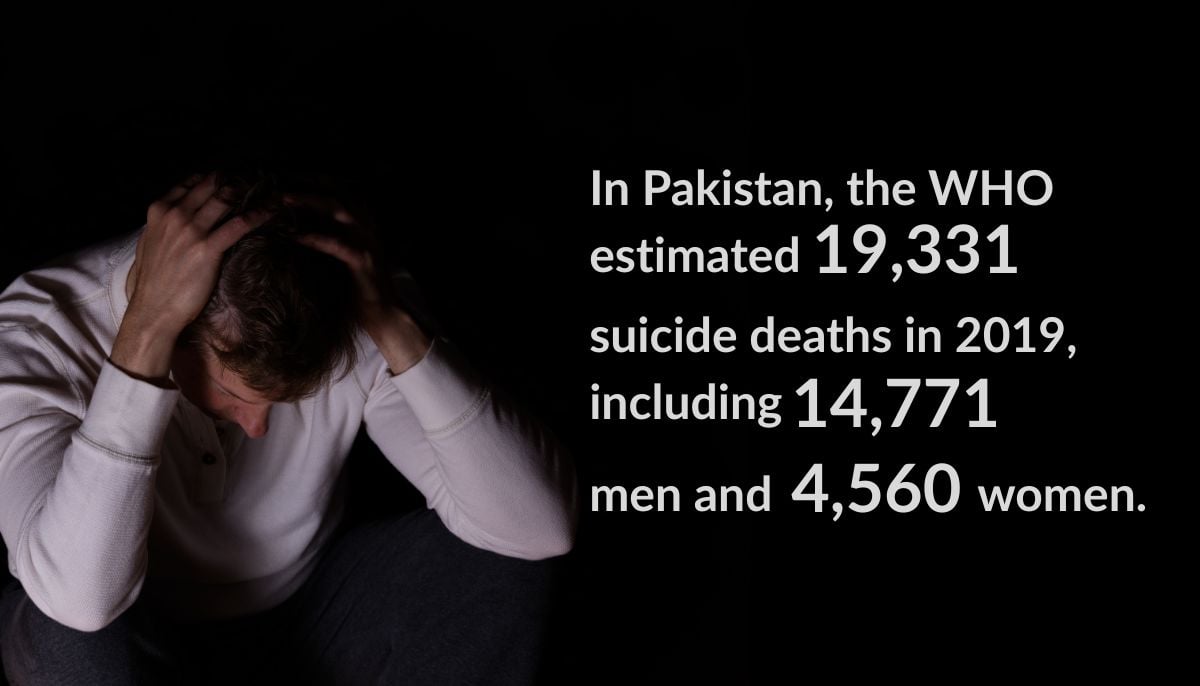

Every year, more than 700,000 people die by suicide worldwide, according to the World Health Organisation. In Pakistan, the WHO estimated 19,331 suicide deaths in 2019, including 14,771 men and 4,560 women. Newspaper reports 2,295 suicide cases in just two years (2019–2020), with 62% males committing suicide. However, conversations about mental health remain taboo in the country, and people continue to suffer in silence.

As for Uroosa, who was facing postpartum depression, she had no name for it back then, and she couldn’t find any safe space to address it. Fearing judgment, she kept her struggles to herself. “I didn’t share with anyone, nor did I ask for help,” she says. “After childbirth, I used to feel very good. I was getting care and attention, which made me feel very special,” she recalls. Yet beneath the surface, unsettling changes began to unfold. “I started getting upset over trivial things, even people’s nagging remarks about the baby or my health started irritating me.”

When she tried talking about it with her husband and in-laws, her concerns were ignored. “Their response was too casual, like, ‘these things are part of every woman’s life.’” With two children born in quick succession and constant tensions with her in-laws, her world began to fall apart. It was not an impulsive act, she admits. “I had been struggling with this conflict for two years. At that time, the only thought on my mind was to end it for once and all.”

Pakistan marked World Suicide Prevention Day 2025 on September 10, 2025. This date holds profound significance for countless families who have silently endured the loss of loved ones who took their own lives. To bring prevention, the global theme for 2024–2026, “Changing the Narrative on Suicide,” also highlights the urgent need to break stigma and encourage empathy. In this effort, the voices of survivors bring perspective and hope to a conversation that is too often left in silence.

With her remarkable courage, Uroosa shares her story and reflects on the turning point that led her to survival. “After my suicide attempt, for eight months, my husband became my rock. He passionately supported me to a normal life.” Her parents also stepped in, caring for the children so she could find moments of relief. “My husband encouraged me to take different courses. Whenever she went out to refresh her mind, her mother looked after the children, freeing her from concern for their safety.”

Uroosa’s story is far from unique. Postpartum depression is one of the least acknowledged conditions in Pakistan. New mothers are expected to resume household roles immediately after childbirth, with little understanding of the hormonal and psychological changes they face. As health experts describe, postpartum depression can result in chronic stress, self-blame, and suicidal thoughts.

Why do suicides happen?

In Pakistan, most suicide cases reflect factors such as social, cultural, and economic pressures. Dr Arslan Akhtar Ali, founder and CEO of Psychology Experts and a survivor of two suicide attempts himself, addresses the urgent need to raise awareness and strengthen prevention efforts. “To move towards prevention, we must understand the history and changing patterns of suicide trends in the country, as there is no national data available on it,” he says.

He further points out that suicide in the country is a complex issue, yet there is no national registry to capture its true scale. Citing alarming numbers reported by the WHO and other non-government organisations (NGOs), he notes that reported suicide cases rose from 7.3% in 2020 to 17.63% in recent years. “Youth, in particular, are increasingly vulnerable. They are bombarded with information. This constant exposure to digital platforms creates impatience, stress, and distorted self-worth.”

Economic pressures also play a major role. “The current economic crisis is one of the top triggers. Thousands of students graduate every year, knowing the job market has little room for them. The uncertainty about their future is pushing many toward mental distress,” Dr. Arslan explains.

Furthermore, he explains that gender expectations deepen the divide. Men are expected to provide for their families, while women suffer domestic abuse at the hands of their in-laws and workplace exploitation. Dr Arslan recalls one case of a female journalist pressured by her superior for sexual favours in exchange for a career promotion. “Imagine the trauma of not only enduring harassment but also having no safe outlet to share it,” he notes.

It has been established that suicide in Pakistan is not confined to certain social roles or gender orientation. It is a wider crisis shaped by multiple factors ranging from academic burdens and economic uncertainty to stigma and lack of professional care. Another perspective on this crisis is Saira’s survival story, a bright student who found herself struggling under the new challenges of mental stress and depression.

A young woman’s dreams interrupted

Saira* describes herself as a once “enthusiastic teenager with a pampered childhood.” She grew up excelling academically, with ambitions of becoming a writer. But her aspirations clashed with her father’s expectations. Now established in a senior career role, the 30-year-old writer and communication specialist reflects on her journey and the time she came close to giving up on life.

“In a middle-class family setup, you often fail to understand why your parents are against your wishes, while all you ask for are simple things. I was a remarkable student with great grades, but my father forced me to pursue medical studies when I always dreamed of becoming a writer.” Sooner, the conflict grew unbearable for her. “Those two years of college were the darkest days of my life, as for someone who had always secured top positions, failing to grasp science subjects felt like drowning; physics and chemistry simply weren’t for me.”

Saira remembers carrying the burden of shame after her failure. “I was being judged for something I wasn’t even responsible for.” Adding to the academic strain were domestic tensions with siblings and parents. The growing stress left her with stage two migraines and severe insomnia, diagnosed at the age of 21.

“I now see my young self struggling to make my family understand that these emotions are real and I am being hurt emotionally and mentally. I was hurt by the way they were treating me. I couldn’t bear the pain of being ignored like I did not matter at all. Call it an impulsive decision, but I was pushed to the edge and I attempted suicide,” she recalls as tears well up in her eyes.

With her voice trembling, she said, “It is painful to recall the details, as she still struggles to believe she survived it all. “The events of that night are still fresh in my memory, as I remember before attempting it, I took a paper and wrote a note for my mother. The writer in me, I thought, deserved at least a moment in this life.”

Saira’s family was too afraid of police involvement, and they avoided her hospitalisation. “I received aid at home, and that’s it. A trauma for a lifetime. But worse than the trauma was the stigma; I was forever marked as someone with ‘troubled mental health.’”

Saira survived her suicide attempt. However, the aftermath of mental stress and trauma left deep scars on her personality. By the age of 23, her hair had turned white, her eyesight had weakened, and her insomnia never improved. “I suffered shame in the eyes of my close family members, as if I was being judged, misunderstood, and ignored for all the wrong reasons.”

Surviving the course of mental trauma, Saira believes that she was one of the few fortunate people in the world who found the strength to recover. “As they say, there is dawn to every night. I turned to reading and writing. It wasn’t easy, it wasn’t a speedy recovery, but my love for writing gave me the courage to apply for a master’s in mass communication, and to everyone’s surprise, I secured admission. That was when life began to change.”

Smiling through tears, she adds that her friends played a pivotal role in her transformation. “They supported me like a lifeline during my toughest phase.” With time, she not only completed her master’s but also earned a scholarship for her MS. Today, she works in a leading organisation and continues to write and inspire people.

Prevention and hope

The survival journeys of Uroosa and Saira show that recovery is possible when timely support and intervention are provided. Expanding on this, Dr Hafsa Sheikh, a resident in internal medicine, highlights ways to achieve systemic suicide prevention. “Suicide prevention is not just the responsibility of medical experts; it requires a collective cultural shift towards acceptance, empathy, awareness, and early action,” she emphasises.

Identifying multiple contributors, such as untreated mental disorders, depression, substance abuse, financial struggles, relationship breakdowns, and chronic illness, she notes that many suicides are impulsive, but timely support could save a life. “Students face immense academic pressure, while professionals struggle with workplace stress. We must recognise that these burdens are real.” She further points out practical steps to fight the crisis, including encouraging coping mechanisms like meditation, physical activity, and creative outlets, and incorporating counselling services in schools, colleges, and workplaces.

Moreover, Dr Hafsa offers advice for starting conversations: “Choose a safe, quiet space. Ask open questions like ‘How do you feel?’ Listen without judgment. Don’t be afraid to ask directly if someone has suicidal thoughts; it gives them permission to open up.”

For an effective prevention approach, Dr Arslan stresses awareness campaigns. “Like polio vaccination campaigns, we need widespread messages to normalise mental health conversations. People must know that seeking help is not shameful.”

Addressing the trauma, Uroosa slowly found her way back. “Don’t stay silent, share your feelings with a close companion or family member,” she now tells other women struggling with mental stress. “Depression makes us believe in things that don’t even exist. But life is worth living for.”

A shared responsibility

Uroosa and Saira’s voices are a reminder that suicide is not a crisis, but it is a lived experience. World Suicide Prevention day and month is about creating space for those still struggling. Dr Arslan urges, “We need to normalise terms like bipolar disorder so people can start conversations without fear. Silence only feeds the crisis."

"Seeking help is not weakness; it is strength. Together, we must build a culture where mental health is protected and struggles are acknowledged. The society should be strong and mature so that no one feels suicide is their only option," he concludes.

* Names and locations have been changed to protect the identity of the survivors.

Bakhtawar Ahmed is a freelance journalist covering gender issues, cultural and societal trends. She can be reached via email at [email protected].

Header and thumbnail image via Canva