Pakistani artist explores grief, memories, and identity through art

Mohsin Shafi carries with him a colossal but delicate legacy, touching upon the sense of belonging, loneliness and grief

Grief is subjective. For some, it takes a visible form: reflected in their eyes, on their faces through their expressions, in the clothes they wear, in the way they carry themselves, and in their hidden, hesitant smiles. For others, it remains obscure, often observed in their conversations, in their silence, in the messages they exchange, or in the way they cook and eat their meals. It continues to linger for days, weeks, months and even years. At the Lahore-based artist Mohsin Shafi’s exhibition, 'The Anatomy of Becoming', grief finds texture, weight and form on the floor of Karachi’s Canvas Gallery, which housed Mohsin’s deepest, most intimate memories.

“The process of creating these works seeped into my veins like a slow — moving tide, disguising itself as nostalgia and yearning. While going through my family archive, I realised that memory isn't a timeline; it's a gravity field,” the artist said in a statement, describing his artworks at the exhibition where shards of his recollections were carved into porcelain, sewn into fabric, painted on a canvas, hand drawn with colour pencils and ballpen, brought to life by resin and natural flowers, assemblage and mixed media — all tenderly gathered with the hope to never forget. Mohsin, at the heart of his exhibition, carried with him a colossal but delicate legacy, touching upon the sense of belonging, loneliness and grief.

“It bends and warps around loss, absence, stretching it like an accordion. Memory doesn't archive; it contrives.”

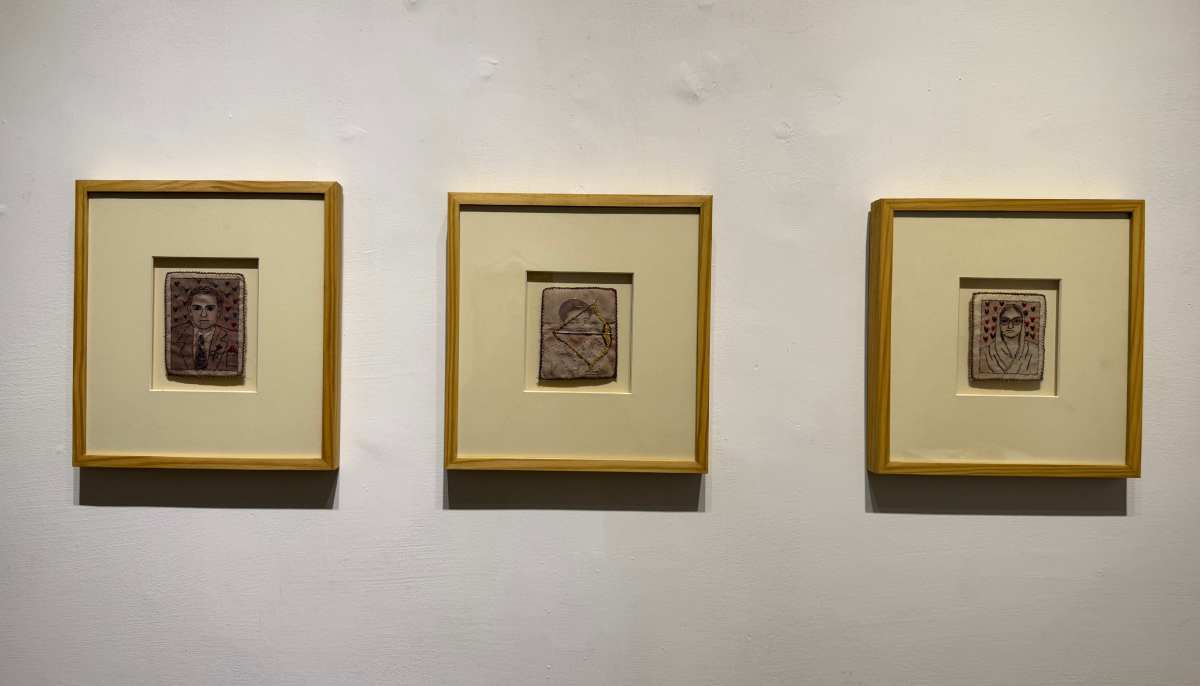

I begin my stroll around the gallery with Mohsin’s artwork 'Dil Jan Sadkey'. For this piece, the artist not only stitched the contours of his late “amma and abba’s” faces into fabric, but also placed in between their frames the thread of his own being. 'Sadkey' — Mohsin’s self-portrait — is placed between the 'Dil' and 'Jaan', his parents’ portraits made using threads. This artwork carries the weight of their absence — a mother no more, a father lost to death and no one else to share the grief with.

“First, I lost my mother, then I lost my father. I was an adopted kid, so I don't even have siblings. It's talking about the trauma of loneliness,” said the artist, whose artwork emerged as an intimate conversation with the departed and the silent revelation of the trauma of loneliness.

Just a few steps away were some intricately sculpted collars of shirts and kurtas worn by Mohsin’s father, who passed away last year.

“I wanted a kind of safety to it, so that when one takes it out, they’re careful while doing so. A collar is otherwise an everyday, regular thing. When I turned the pieces into porcelain while making, they automatically began breaking, and I thought they’re just so fragile — something I wanted to communicate through my work,” said Mohsin, commenting on the sensitivity that comes with the medium.

'Tan Zaib' was another striking piece that carried superimposed photographs of Mohsin’s parents nestled inside a 24x20-inch frame with borders made using wooden tailoring rulers and a hanger holding it all together. The background displayed an old Urdu Rs2 tailoring book, 'Tan Zaib' — published from Karachi during the 70s and 80s — found in the artist’s mother’s collection, allowing him to cherish it as one of her keepsakes.

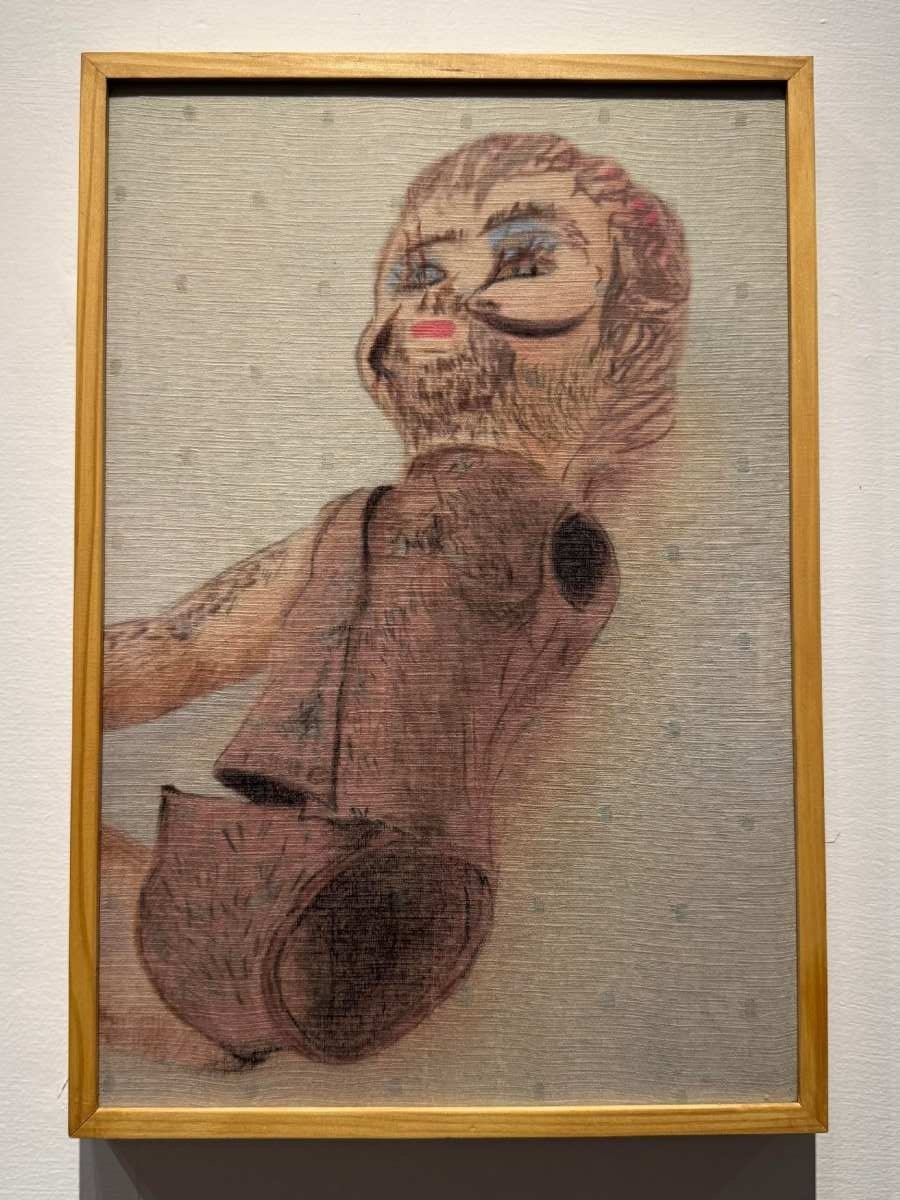

One of the most haunting artworks in the gallery by Mohsin reminded me of Gaza. His drawings, depicting a traumatic childhood, reflected the pain of children in the occupied land, witnessing a genocide. Hand-drawn sketches of a doll-like figure displayed in different frames presented a body without limbs and head, a lot similar to the barbarity we have been witnessing on our smartphone screens in the aftermath of October 7, 2023, as innocent Palestinians, particularly children, in Gaza continue to be annihilated by Israel. Mohsin said these drawings talked about the abuse which comes with being different. As a child growing up in Pakistan, the artist was immensely bullied and poked fun at.

“At the time, I didn't have the courage to say anything to them, so these drawings bring out the aggression I couldn't express back then. Because now that I've lost everybody, and am also on this journey of healing myself, these drawings are somehow helping me open up and do my own therapy,” he said.

Mohsin describes the drawing’s line quality as “wild” and “scratchy”. He uses charcoal — a sharp medium that resonates with the theme of his work and runs through the narrative itself. “It is very metaphorical,” he said, and added, “People find them morbid. Everybody who came [to see the show] said they don’t want to look at [these drawings]; when in fact, they don't want to look at their own childhood.”

To Mohsin, that didn’t matter. “These are haunting, and that's exactly what I wanted to see. People said we wouldn’t want to buy it and place it in our homes — that is not the purpose. We run away from the truth and acceptance, and we go far from it. We look at things at a superficial level and enjoy.”

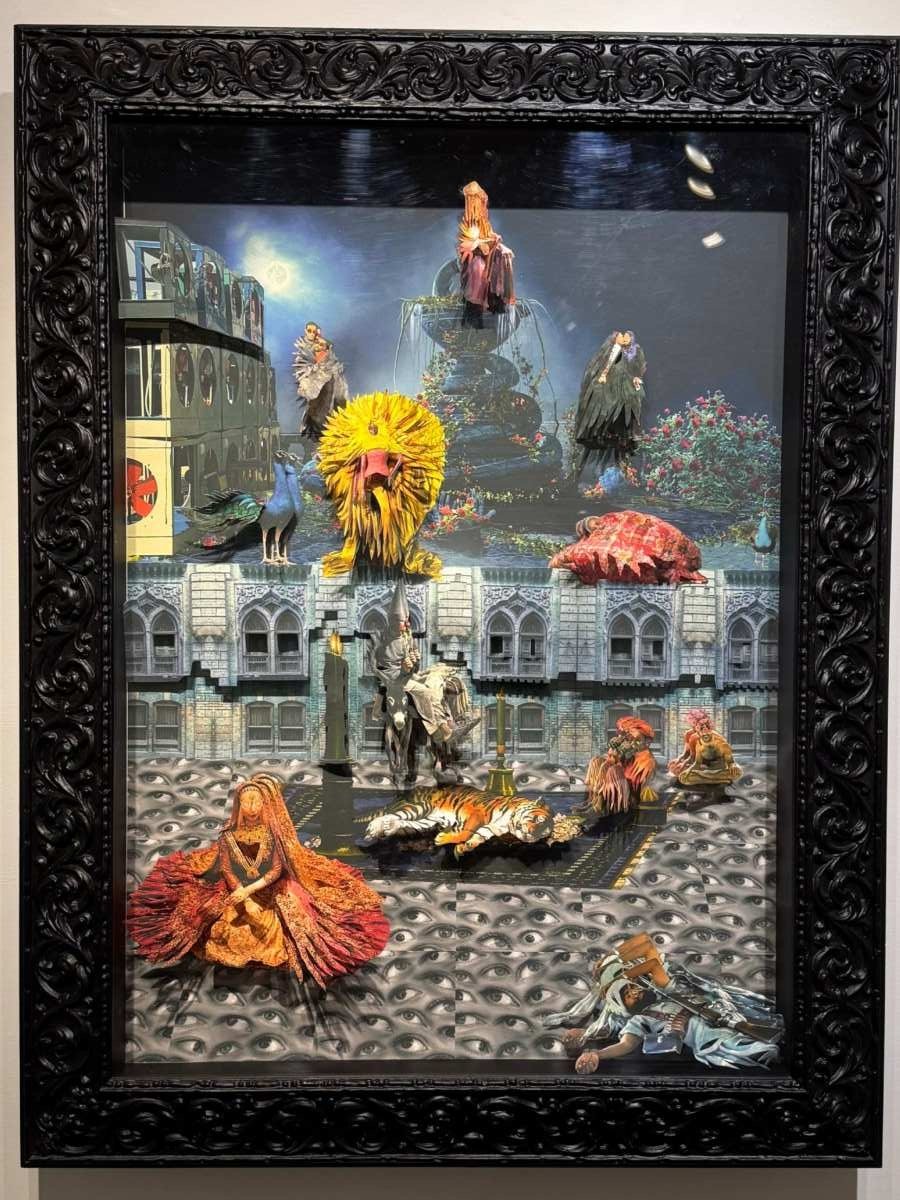

The wall opposite the gallery door was adorned by an eccentric piece — a 3D artwork resembling a children’s pop-up storybook made using paper. Through this piece, 'Adventures Of The Cozy Nights', Mohsin talks about safety and cosiness from a different perspective. The eyes in the piece represent looking at oneself critically. Then there is a groom and a bride, street hawkers, someone is sitting on a donkey, and another person is sitting on a lion. There is also a chowkidar (watchman). The entire piece tells the story of a single night — depicting all that’s happening at different places with different people and what they are feeling.

“It’s like going through a newspaper where on the first page you read about poverty and politics, then on another page there is writing about glamorous fashion,” he said.

To me, it also reflected the contrast currently being observed around the world, where on one hand some people lack access to food, clothing and safety, while others live their lives unabashedly — like what we’ve been witnessing in lands like Gaza, Sudan, Yemen, Syria, and Lebanon, to name a few.

“I've also been seeing these dark images. This was also something important and was consciously in my mind, because this is what I’m seeing on social media. As an artist, you can't avoid that. A few days back, I saw a little [Palestinian) girl crying for her father, who was killed. After I saw that, I couldn't sleep for three nights. It also helped me realise how I was lucky and spent so much time with my father, while this kid would not get to spend 40 years of their life with their father,” said Mohsin.

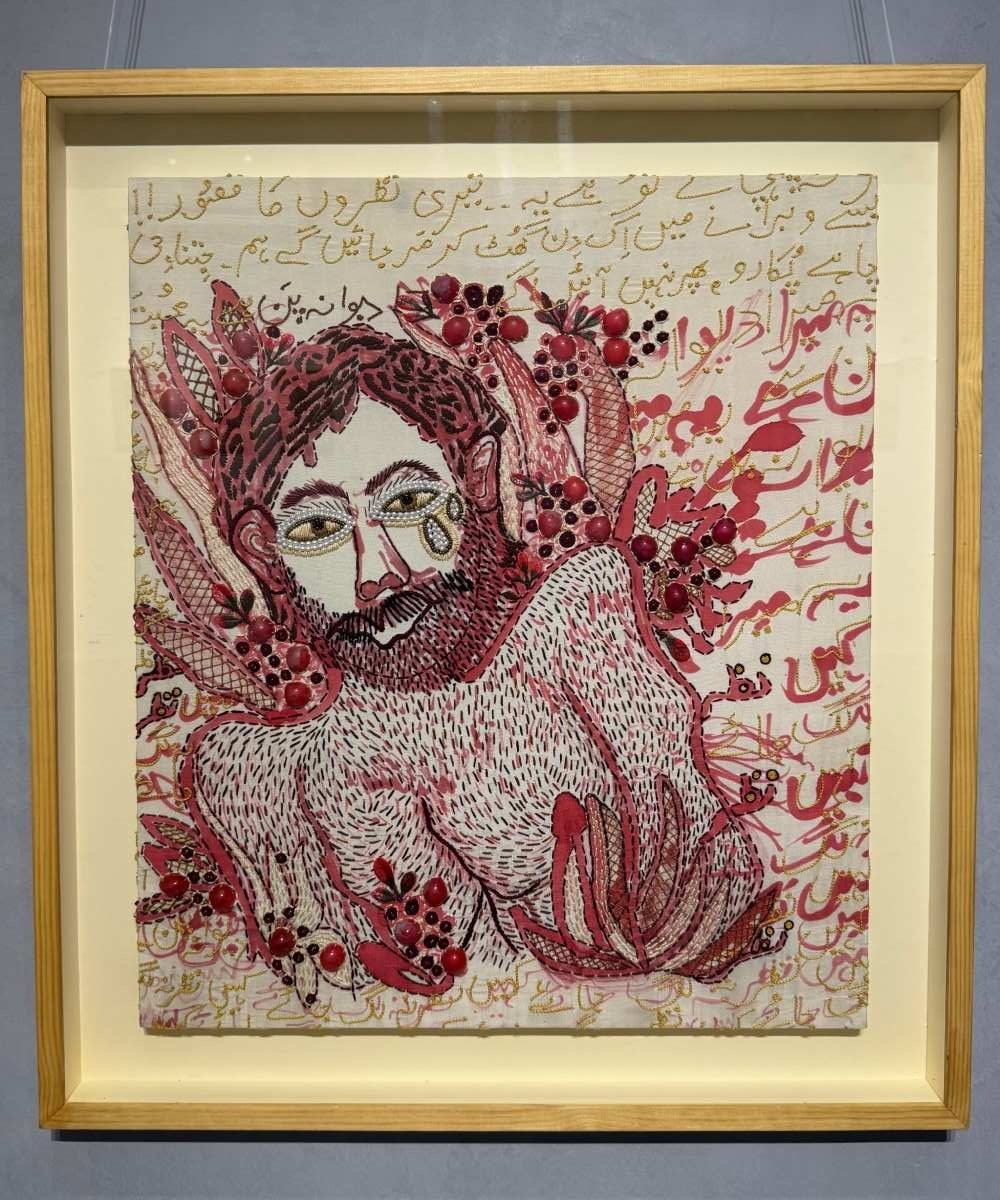

As I moved ahead observing Mohsin’s intricate work, another one of his self-portraits caught my attention. The piece displayed lyrics of a Hindi classic song, Yeh Mera Deewanapan Hai, sewn into the canvas with golden dori (string) work. It was one of the songs his father loved, sung by his favourite singer, Mukesh, from the 1958 Hindi movie Yahudi. Self-portrait, however, showed the artist weeping with two teardrops falling down his cheeks, portraying the crying emoji we often use to express sorrow on WhatsApp messages and social media.

“When my father passed, people would send a crying emoji… I kept wondering why not many people came for condolences. My closest friends came, but mostly messaged on social media, sending an emoji. Our happiness and sorrows have turned so static that they don’t have any life, but are limited to comments, messages and emojis — not even a sentence,” Mohsin described, adding, “I wonder if I’m the only crazy person to think that way and do others not feel the same. People justified saying, ‘Nobody has the time, at least they’ve sent an emoji. ’ I wondered if sending an emoji was enough.”

Mohsin spoke about how, as an artist, when one makes art in their studio while going through grief, thoughts just gather on their own. As we continued our conversation about this particular piece, a Mohammad Rafi song — Ye Zindagi Ke Mele — from the 1948 Dilip Kumar and Nargis starrer Mela played at the gallery, reminding me of my grandfather, with whom I watched the tragic movie back when I was a mere eight-year-old. The song, playing in the background, reignited my grief of having lost him over 22 years ago and also revisit the fragility of life and all that it brings along.

Among his many artworks sharing his relationship with his late parents, Mohsin included another unconventional way to keep his father’s memory alive — dentures created using transparent resin and dried flowers which became an odd addition to the show.

“These were my father’s dentures. It depicts laughing back at the world but with a nice smile… I added these original dried flowers to the mix. It was a way to also preserve his smile,” said the artist.

Moving forward, Mohsin points towards a drawing representing the recent war between Pakistan and India. In the piece, two unclothed men represent the two countries, while there is "an angel or a guard looking over". While describing the artwork, he spoke about conveying the pain of those who were impacted by the brief but devastating war on both sides of the border, particularly those residing in the Kashmir region, falling under the territories of Pakistan and India. Here, Mohsin again reflected on the fragility of life. The artwork, at its centre, carried a heart wrapped around with a time bomb. “It questions how you can do that to the heart of another human being and take their life,” he said.

One of Mohsin’s most cherished artworks was 'Confessions of a Secret Lover, ' a collection of items stolen as souvenirs by the “kleptomaniac” artist, as described by popular fashion personality Frieha Altaf, who was also attending the show. It portrayed one’s association with certain things that they want to keep. He is showcasing this work for the third time. As for stealing, Mohsin stopped doing that nearly five years ago. Among the many stolen items by Mohsin was a saag cutter from his nani’s kitchen, a shoe polish brush from his nana’s belongings, a withered rose, a paint brush, a cigar, a seashell, a soormachu (a wooden kohl applicator) from his mother’s soorme dani (kohl container), her spectacles, her tasbeeh (prayer beads), his khala’s (maternal aunt’s) scissors, and lots more.

“During my childhood, I was fond of doing this. This artwork shows that I’ve been stealing items from my friends or people I know — just in memory of them. Everything has a whole story about it. I wanted to show the childlike side, and stealing is a childish habit,” he said, adding, “There is some kind of naivety to it because the stolen items are random objects and not money or anything expensive.”

To relive these memories with Mohsin at Canvas was a lesson in living a spontaneous life, accepting the vulnerabilities, anxieties, trials and tests, along with moments of joy that sneak in between.

"Through The Anatomy of Being, I've learned that our remedies lie within us, and within us unfolds the entire universe. The challenge is to turn our tragedies into triumphs," mentioned the artist, describing his show.