In Pakistan, disasters rise from rot of governance, not wrath of nature

When disasters strike in Pakistan, whether it is dumper trucks crushing bikers commuting on Karachi’s roads, buildings collapsing in city centres, or floods sweeping away communities, the official response always seems to follow a familiar pattern: denial, deflection, and blame-shifting.

Is it the wrath of nature, or the consequences of our own making? Let’s find out.

Rarely does anyone in power pause to question themselves or the responsible authorities for obvious negligence. The truth is that the very institutions tasked with regulation and public safety have long failed to perform their duties.

Illegal buildings go up unchecked after bribes or because of someone’s influence and appear on floodplains, even some large housing schemes rise on riverbeds, and encroachments are allowed to eat into public spaces, all while authorities look on.

Behind every collapsed building, flooded neighbourhood and washed-away hotel or restaurant is a trail of approvals, ignored warnings and officials who turned a blind eye.

And when the devastation unfolds, instead of accountability, citizens are accused of carelessness, as if they had built without permission in the dark of night or decided to reside in a property that appeared in a day. From cutting trees to raising illegal constructions, these violations never happen out of sight; they thrive under a system where oversight is traded for influence, negligence, or corruption.

In an attempt to understand the reasons behind the lack of governance, we spoke to people who have been — or still are — part of the system that allows these failures to persist. From Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s floods and timber mafias to Karachi’s crumbling infrastructure and Punjab’s illegal housing societies, the story appears to be the same: laws exist, but enforcement hardly does.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Floods, logging, and legacy of negligence

Since late June 2025, floods across Pakistan have claimed over a thousand lives, with KP recording the worst death toll with 504 deaths, 218 injuries, and thousands of homes destroyed and hundreds of lives lost. It was not the first time either as some communities have still not recovered from the catastrophic super floods of 2022.

The authorities at the time had acknowledged that illegal construction of hotels and resorts along River Swat’s banks had magnified the destruction. The images of entire commercial tourist structures on riverbeds going down with floodwaters raised alarm bells nationwide.

The then–deputy commissioner of Swat, Junaid Khan, had imposed Section 144, banning all construction on the riverbed. He had claimed that most of the structures were built before the Rivers Protection Act 2014, which prohibits construction within 200 feet of rivers.

This year, as floods returned, so did the issue. This year on August 22, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif publicly held illegal constructions along waterways responsible for the rising death toll, questioning how long governments would keep compensating for such "unlawful acts" — acts that keep happening, one disaster after another.

Adeel Shah, KP secretary for planning and Development, agreed that illegal structures have compounded the disaster.

“If these buildings weren’t there, the losses wouldn’t be this severe,” he admitted. “Now we’ve launched a province-wide anti-encroachment drive. Every district’s data is being reviewed with GIS mapping, and the Chief Secretary personally oversees progress.”

A new government agency, Land Rules and Building Authority, has been formed to centralise building approvals and eliminate overlapping jurisdictions. But Shah conceded that enforcement remains a major hurdle.

“Whenever we act, people go to court and get stay orders,” he said. “Thankfully, the High Court and Supreme Court have now directed strict action — we can’t afford to face the same tragedy every year.”

Beyond construction, illegal logging has worsened floods across KP. According to official estimates, Pakistan’s forest cover has dropped from 3.78 million hectares in 1992 to 3.09 million hectares in 2025 — just 5.2% of the total land. KP accounts for 95% of the loss, fuelling floods in Buner, Shangla, and Swat.

“There was a time when our population was smaller and police were strong,” shared Saleem Khan, former KP chief secretary. “Now, when you report a tree being cut, police say someone’s lying dead down the road — should we chase the killer or the logger?”

He also suggested forming specialised enforcement bodies, leaving criminal matters to police but tasking a new agency with enforcing environmental and construction laws — a model Punjab has begun experimenting with.

Shah added that forest officers in KP have been trained and armed to tackle the powerful timber mafia, though many have been attacked or even killed in the line of duty.

“This mafia can’t operate without insider help,” he admitted. “We’re identifying and removing those involved — 100 to 150 officials have already been dismissed.”

KP’s new Climate Action Board Law aims to institutionalise protection and enforcement, but Shah warned, “We can plant a billion trees, but it won’t matter if others keep cutting them. Until enforcement is real, we’ll keep planting and losing at the same time.”

But former secretary Khan believed the problem runs deeper than illegal buildings or heavy rains.

Khan pointed towards unchecked population growth and poor planning as root causes. “We fault people for settling along drains and rivers, but we’ve failed to stop it. We still run the system manually — nothing has evolved.”

Sindh: Illegal constructions, flooded streets, and fatal roads

In Karachi, even light rainfall can bring the city down. The failing sewerage system hasn’t got a significant upgrade for decades. On August 19, 2025, heavy rains once again submerged major roads, trapping motorists and claiming lives.

As the city drowned, PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari’s earlier statement — "jab ziada barish hoti hai to ziada pani ata hai (When it rains more, more water comes.)" — echoed bitterly among citizens.

Karachi’s woes extend beyond drainage. Illegal constructions have been mushrooming unabated in the metropolis for ages. In 2024 alone, the Sindh Building Control Authority (SBCA) demolished over 1,500 unlawful structures. But the question remains — how do illegal buildings rise in the heart of the city under the noses of authorities?

The Nasla Tower case is a striking example. A 15-storey residential building, constructed illegally, stood unchallenged until the Supreme Court ordered its demolition.

The problem doesn’t end there. Karachi’s skyline is littered with dilapidated buildings; after the Lyari building collapse in July that killed 27 people, the government admitted that nearly 600 buildings across the city are hazardous.

And death doesn’t only fall from above. It roars down Karachi’s roads in the form of dumper trucks and tankers — unregulated, overloaded, and deadly. In 2025 alone, 536 people have died in traffic accidents; dumpers and tankers account for at least 64 of those deaths.

Karachi Mayor Murtaza Wahab acknowledged that decades of neglect have created this chaos.

“These problems — encroachments, illegal constructions, negligence — are all the result of weak governance over many years,” he told Geo.tv. “Whenever the city administration acts, stay orders halt progress. The 7,000 encroachments on storm-water drains are one such case.”

When asked why illegal activities happen on the watch of authorities and in the presence of laws, Wahab stated, "This is not only a Karachi issue but a nationwide challenge. From hotels built on riverbeds to illegal housing societies in various provinces, violations have been ignored for years. The present administration is acting seriously, but the scale of the problem created in the past far exceeds the current pace of rectification. It will take time, consistency, and legal support."

When questioned whether citizens should be called out for losses caused by official negligence, Wahab insisted it was not the intention. "People should verify property approvals before investing, but institutions must also strengthen enforcement. That’s exactly what we’re working for."

Critics argue that ordinary citizens rarely have the means to verify legality, especially when corrupt officials and developers collaborate. Wahab denied that his administration was involved in shielding such actors and that his government was providing protection to illegal plazas or constructions.

“Everyone knows when these societies were built and who approved their construction. This city can’t afford further compromises — strict measures are being enforced,” he said firmly.

Punjab: The business of illegal housing

In Punjab, the story shifts from floods to fraud. Encroachments and illegal housing schemes have spread without any serious regulation for years, often in cahoots with local authorities.

Attempts to clear encroachments are met with heavy resistance from the residents. The question remains: Who allowed these settlements in the first place?

Illegal housing schemes have become one of Punjab’s most profitable rackets. Billboards for flashy but dubious societies dominate Lahore’s skyline — names without substance, approvals, or land. Developers launch campaigns, collect payments, and vanish when the money dries up.

A recent example is Theme Park View Society, part of a cluster of 44 illegal projects under the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA). Buyers lost life savings, and only after homes flooded did the government step in.

Minister for Information and Broadcasting Attaullah Tarar clarified that the government will not compensate illegal constructions. But many question the fairness of punishing victims rather than those who approved or ignored the violations.

In a written response, the Lahore Development Authority (LDA) attributed the rise of illegal housing to weak laws, poor coordination, and lack of enforcement.

“Our legal framework offers limited punitive powers,” the LDA shared in a written response. “Coordination with agencies like LESCO, PEMRA, and PTA is weak, and local staff often ignore directions. Developers misuse temporary utility connections and continue to advertise despite bans.”

Court-issued stay orders, limited manpower, and bureaucratic inertia create the perfect environment for such schemes to thrive. The result: thousands of citizens trapped in legal limbo and unliveable housing.

Governance stuck in a vicious cycle

Across provinces, the pattern is unmistakable — weak enforcement, overlapping jurisdictions, and misplaced priorities. Disasters don’t expose new failures; they simply reveal the ones that were left unresolved for decades.

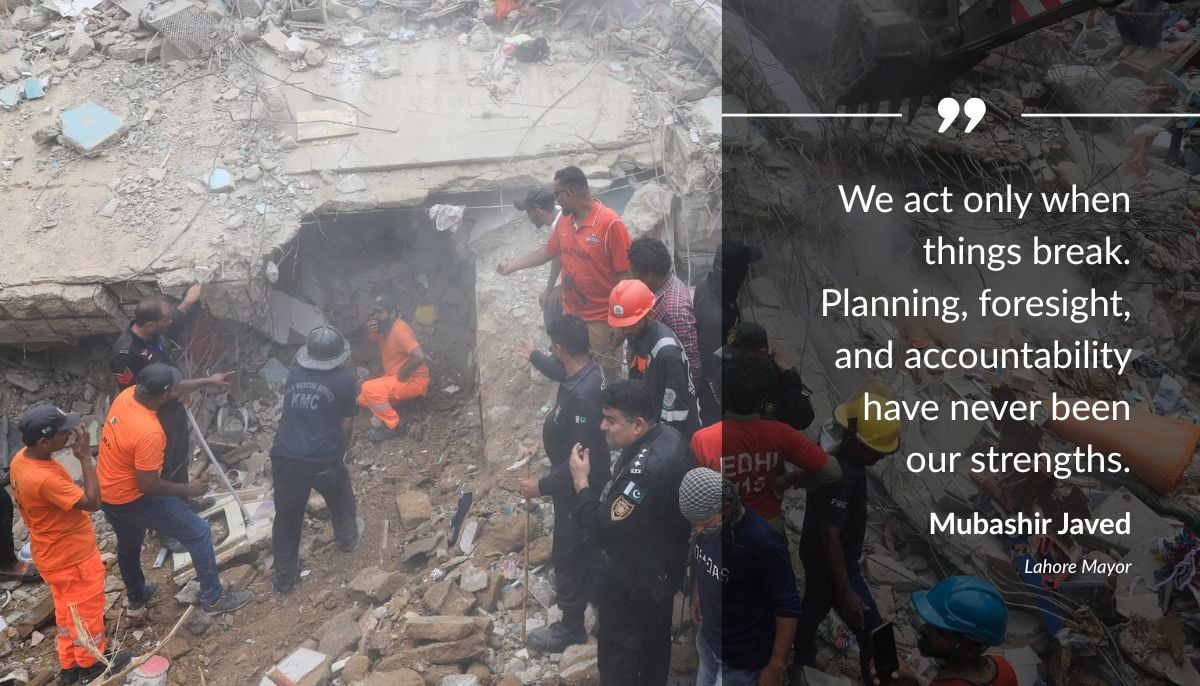

Taking a jibe at those in power, former Lahore Mayor Mubashir Javed said, to be honest, "Governance here [in Pakistan] means running a system for personal gain, not public welfare," he said.

"When incapable people are placed in powerful roles, this is the outcome. We need the right man at the right place — and education that builds skill, not shortcuts."

He lamented that "corruption has seeped into every layer — from the labourer to the bureaucrat — creating a cycle that perpetuates itself."

"Until corruption ends, nothing else will," Javed warned. "We act only when things break. Planning, foresight, and accountability have never been our strengths."

And that may be the most painful truth: Pakistan doesn’t lack laws, expertise, or even awareness — it lacks the will to act before tragedy strikes, or maybe it is deliberate ignorance to protect vested interests.

Momna Tahir is a staffer at Geo News.

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv