Eleven years after APS massacre: Pakistan's unfinished war against terrorism

Memory of schoolchildren killed continues to haunt nation, not only as a symbol of past unity and resolve, but as a moral yardstick

More than a decade after one of the darkest days in Pakistan’s history, the trauma endured by the families of the victims of the Peshawar Army Public School (APS) massacre remains undiminished. Time has neither softened their grief nor dulled their memories. If anything, the passage of years has only intensified the pain. Their children were among the 147 people, 132 of them students, brutally killed when gunmen affiliated with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) stormed the APS compound in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's (KP) capital on December 16, 2014, in one of the deadliest terrorist attacks the country has ever witnessed.

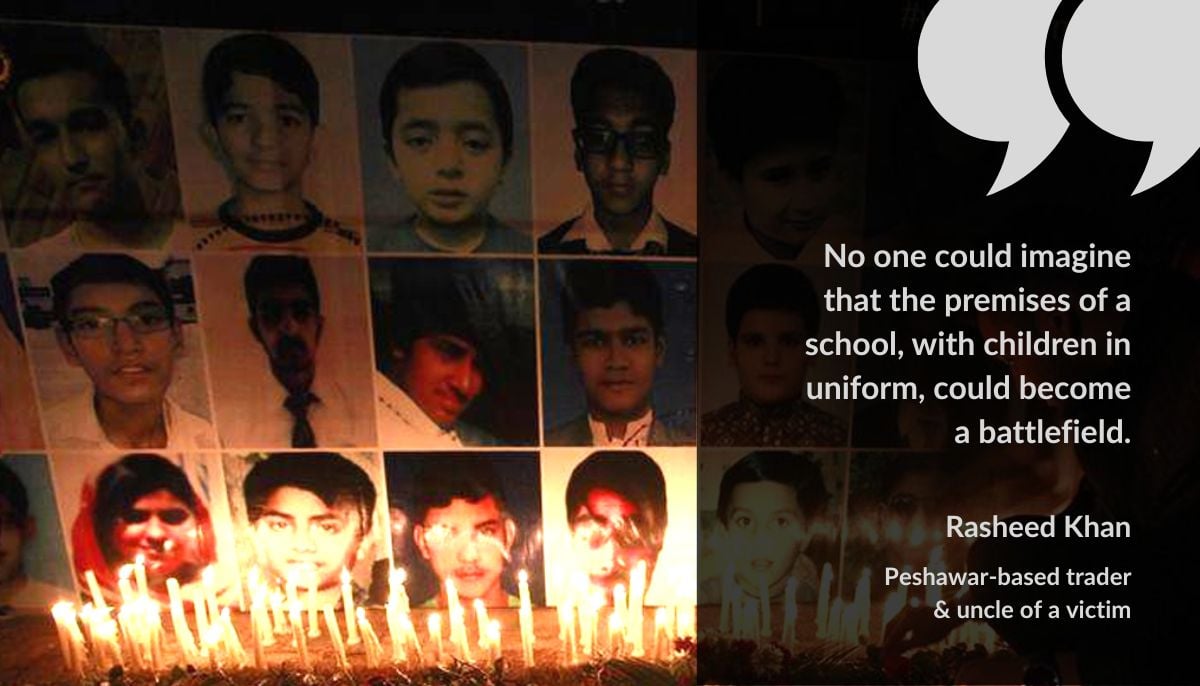

“I can never forget the chaos of that day,” recalled Rasheed Khan, a Peshawar-based trader whose nephew, a tenth-grade student, was among those murdered. “Parents were crying and pleading outside the school gates. Soldiers were rushing in. Children and teachers were running for their lives.”

His recollection remains vivid, marked by disbelief and helplessness. “No one could imagine that the premises of a school, with children in uniform, could become a battlefield.”

Even after more than eleven years, the memories remain raw. “It feels as if nothing has changed,” Khan said recently. “When one looks at the country’s current security situation, it seems our children’s sacrifices were in vain.”

His words reflect a sentiment increasingly echoed across KP and beyond: that the national resolve forged in the aftermath of APS has slowly eroded.

A moment of national rupture

The massacre sent shockwaves across Pakistan, triggering an unprecedented moment of collective mourning and national unity against terrorism. Vigils were held across cities and villages. Though temporarily, political rivalries were suspended. Media outlets abandoned sensationalism in favour of sober reflection. For a brief moment, the country appeared united in the conviction that such violence would never again be tolerated or rationalised.

Analysts and security officials broadly agree that Pakistan’s confrontation with militancy can be divided with unusual clarity by a single date: December 16, 2014. The APS attack marked a decisive rupture in how the militant threat was understood, debated, and addressed. It fundamentally altered public discourse and narrowed the space for ambiguity.

Before the massacre, public debate continued to entertain distinctions within the militant landscape. Violence was categorised, and militant actors were differentiated by geography, intent, and perceived strategic utility. Certain factions of the Pakistani Taliban, most notably the Hafiz Gul Bahadur-led group, were informally described as the "good Taliban" for directing their attacks toward Afghanistan. Others, like the TTP, were labelled "bad Taliban" for targeting the Pakistani state, despite shared ideological and operational ties with the Afghan Taliban and Al Qaeda.

This framing allowed segments of the political class to advocate negotiations, reconciliation, and selective use of force. Militancy, for much of the country’s urban middle class, appeared distant, confined to the former tribal region, unfolding in remote villages or viewed through grainy footage of drone strikes and military operations. Even high-profile attacks, including the assault on Karachi airport in June 2014, failed to dispel the belief that everyday life, particularly spaces associated with children, remained insulated from the conflict.

The attack on APS shattered that illusion.

When gunmen entered classrooms and systematically killed students and staff, they erased the last vestiges of moral or strategic ambiguity. In that moment, the language that had once rendered militancy debatable collapsed entirely.

The unified national response

Eight days after the massacre, political divisions were temporarily set aside as both the civilian government and the military received broad public and parliamentary support to intensify counterterrorism operations. Operation Zarb-e-Azab, which had already been launched earlier in 2014 in North Waziristan, was expanded and accelerated with renewed urgency.

Simultaneously, Pakistan’s political leadership convened an all-parties conference and approved the National Action Plan (NAP), a 20-point agenda that promised a comprehensive counterterrorism framework.

In the short to medium term, the results appeared tangible. Military operations forced many militant groups to retreat across the border into Afghanistan. Terrorist infrastructure was dismantled, command-and-control structures were disrupted, and several high-profile militant leaders were killed. For several years, large-scale terrorist attacks declined sharply. By 2018, officials declared that Pakistan had turned the corner, becoming a “victor from a victim” in the fight against terrorism.

That optimism has since faded.

A resurgent threat

The return of the Afghan Taliban to power in August 2021 marked a critical inflection point. The regional landscape shifted dramatically, and with it, Pakistan’s internal security calculus. The security gains achieved in the years following the APS attack have come under severe strain. Militant violence has resurged, particularly in northwestern KP, while ethno-separatist insurgency has intensified in Balochistan.

According to the Global Terrorism Index, Pakistan is now ranked as the world’s second most terrorism-affected country. Terrorism-related fatalities rose by approximately 45% in 2024, while the number of attacks more than doubled compared to the previous year. This sharp escalation represents a decisive reversal of the relative stability that followed large-scale counterterrorism operations in the aftermath of the APS tragedy.

The deterioration reflects a convergence of destabilising factors, including prolonged political instability, economic distress, governance deficits, and the regional upheaval triggered by the Taliban’s return to Kabul. The new Afghan reality has provided ideological encouragement and, according to Pakistani officials, operational and logistical space for militant groups targeting Pakistan.

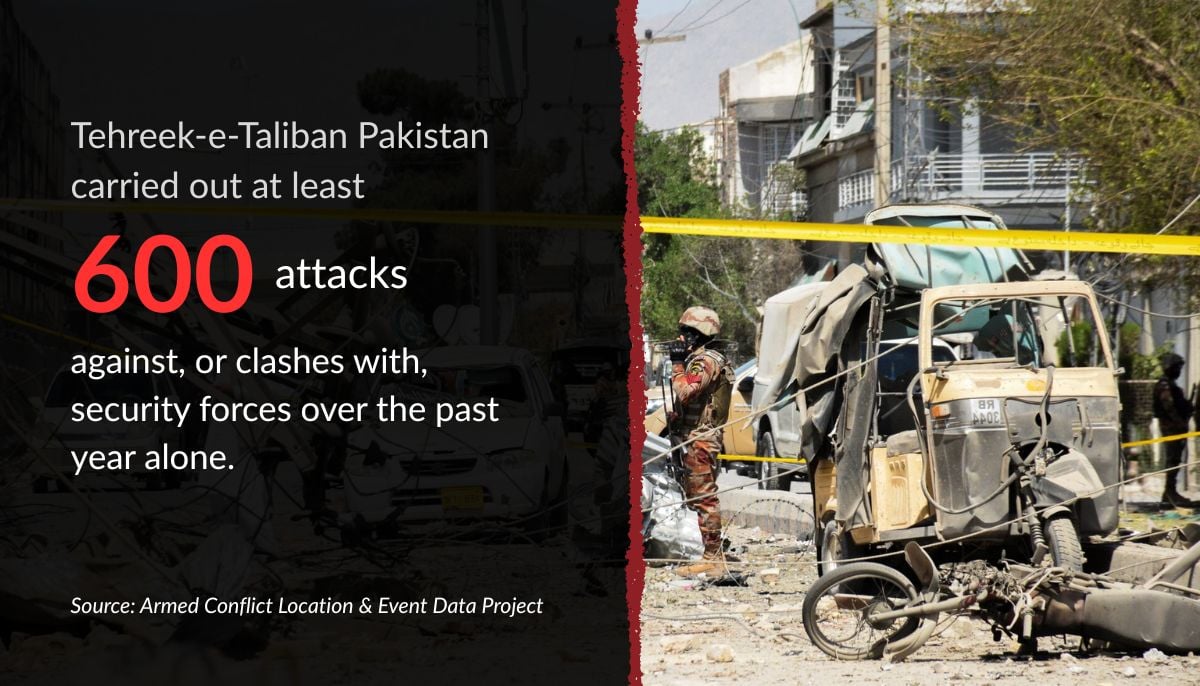

Since 2021, attacks by TTP and its allied factions have increased steadily, reversing a downward trend that had persisted for nearly six years. Although the TTP has not yet regained the operational capacity it possessed during its peak in the late 2000s and early 2010s, data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) indicate that the group carried out at least 600 attacks against, or clashes with, security forces over the past year alone. Notably, TTP activity recorded so far in 2025 already surpasses the total observed throughout 2024.

Pakistani security officials now openly acknowledge that their expectations of the Taliban-led Afghan government were misplaced. Islamabad had assumed that, in exchange for Pakistan’s covert support during the US-led war, the Taliban would restrain or dismantle the TTP—an assumption that has since proven deeply flawed.

“Our assessment proved wrong,” acknowledged a senior security official in Islamabad. While the TTP had previously been weakened by internal fissures, sustained military pressure, and the loss of key commanders in US drone strikes, the group has since reorganised into a more resilient and lethal force.

According to Pakistani assessments, the TTP now operates with the benefit of cross-border sanctuaries, access to resources, and modern weaponry left behind after the collapse of the former Afghan government. claims consistently denied by Taliban authorities in Kabul. Diplomatic engagement has so far failed to yield concrete security guarantees.

At the same time, Balochistan has witnessed a sharp uptick in violence by ethno-separatist groups such as the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA). The province, home to several flagship projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), has seen militants adopt increasingly lethal tactics, including suicide bombings and coordinated assaults on Chinese nationals and security installations.

Constraints and costs

The current security environment in Pakistan demands a renewed focus on its counterterrorism efforts. Yet, analysts argue that the state’s capacity to launch a comprehensive, large-scale operation akin to Operation Zarb-e-Azb is now severely constrained by a confluence of political, economic, and institutional limits. The experiences of the past eleven years, since the APS massacre, have exposed the inherent weaknesses in Pakistan’s long-term strategy, leading to a complex and resurgent threat landscape.

Economic pressures are equally severe. Counterinsurgency requires sustained investment in intelligence, surveillance, policing, and development, even as Pakistan grapples with mounting debt, fiscal austerity, and external financing pressures. The space for prolonged military engagement is narrower than it was a decade ago.

Crucially, the current security challenge, defined by the dual threat of religiously inspired militancy and ethno-separatist insurgency, cannot be addressed through kinetic operations alone. The experience of the past decade underscores the limitations of fragmented and reactive counterterrorism approaches that prioritise force while neglecting governance, justice, and political reconciliation.

Public sentiment has also shifted markedly. The human and financial costs of the post-2014 operations remain vivid: thousands killed, millions displaced, and entire communities uprooted in the former tribal districts.

Today, public support has markedly eroded, with widespread opposition to any new large-scale military campaign in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, including from the PTI, the province’s ruling party, reflecting enduring concerns about civilian harm, population displacement, and human rights implications.

A fractured present

Eleven years after the APS massacre, its memory endures not merely as a national trauma, but as a benchmark against which Pakistan’s evolving security failures are increasingly measured.

The unity and moral clarity that briefly emerged in December 2014 have steadily dissipated, replaced by political fragmentation, institutional fatigue, and a creeping normalisation of violence that once shocked the nation into collective action.

The erosion of that resolve has had tangible consequences. Militant groups have adapted, reconstituted, and exploited governance vacuums, while the state’s response has oscillated between reactive force and strategic hesitation. The absence of sustained civilian oversight, policy continuity, and political consensus has allowed the security challenge to metastasise rather than recede.

Pakistan’s future security, analysts argue, hinges not on the replication of past military operations, but on the development of a coherent, civilian-led strategy that integrates kinetic measures with governance reform, justice delivery, economic inclusion, and credible regional diplomacy. Without this shift, the country risks repeating a familiar cycle: crisis, reaction, temporary suppression, and eventual relapse.

For residents of KP, the resurgence of militant violence has reopened wounds many believed had finally healed. The sense of abandonment is particularly acute in districts bordering Afghanistan, where renewed insecurity has once again disrupted daily life and displaced families.

“A decade ago, the APS tragedy transformed public helplessness into a united national resolve,” said Muhammad Asghar, a school teacher in Bajaur, where a limited military operation against the TTP continues to displace families from border villages. “Today, people feel abandoned.”

“There is a perception that the state is more focused on internal political conflict than on the safety of its citizens,” he added.

This perception, widely shared across the province, reflects a deeper crisis of trust between the state and its people. The fear is not only of violence itself, but of institutional inertia, that warning signs are once again being ignored until another catastrophic rupture forces action.

“It feels as if the country is waiting for another tragedy like APS before it wakes up again,” Asghar said.

Eleven years on, the memory of the children killed in Peshawar continues to haunt the nation, not only as a symbol of past unity and resolve, but as a moral yardstick against which present failures are increasingly measured.

Zia Ur Rehman is a journalist and researcher with extensive experience covering security, political developments, and social movements. He posts on X @zalmayzia

Header and thumbnail image by Geo.tv