The manhole fiasco: A policy shortfall, not a maintenance failure

The clash of coordinates and contracts ensures that while officials trade allegations, the fundamental duty to protect the public is lost

The death of a three-year-old child after falling into an open manhole is not only a tragedy but a prosecution-worthy state failure.

For years, media reports have highlighted Karachi’s urban breakdown, now at crisis level, with children among its most vulnerable victims. Yet, instead of addressing the multifaceted issues of the city, the government is preoccupied with political theatrics and blame-shifting. This systemic neglect has been fostered by a fragmented administrative structure which, by its very design, shields powerful officials from accountability.

“We’re living in a depressed and extremely unsafe city,” a ride-hailing service driver, Muhammad, said while lamenting the total absence of governance. “My parents don’t know if I will return home or not; their anxiety is palpable when I am leaving to work as a driver for 18 hours a day on the unsafe streets of Karachi”. He further expressed the constant fear of navigating the city’s crumbling infrastructure. “On every route, one never knows when a new pothole will appear or when a car wheel will get stuck in an open manhole. Roadwork seems never-ending.”

Muhammad is not the only one to feel this way. Every person in Karachi, whether they are walking, riding a motorcycle, or driving a car, feels this way, especially if they are parents of young children. Karachi feels unsafe and often unwelcoming. But when the government is questioned or confronted about its role, it does not shy away from victim-blaming. This strategy enables officials to deflect accountability onto the most vulnerable victims.

An official of the local government believes that manhole maintenance was assigned to union committees (UCs) to blame them for the next incident. Referring to the CCTV video that followed the recent incident, an official said, “If one looks at the video, the kid ran from his mother, towards his father for more than four feet on a busy thoroughfare. Parents need to be vigilant when going out instead of focusing on shopping”. Statements like this imply that negligence by the parents is the primary cause, rather than the state’s systemic failure to secure a busy thoroughfare from fatal hazards. It is also a symptom of the disconnect between the state and the city it is supposed to serve.

Architect Kamran Ansari calls this an issue of not just accountability and accessibility, but also a matter of awareness. “If those who run the system are unaware of the existence of an infrastructure element, how can they be expected to maintain it?” he asked.

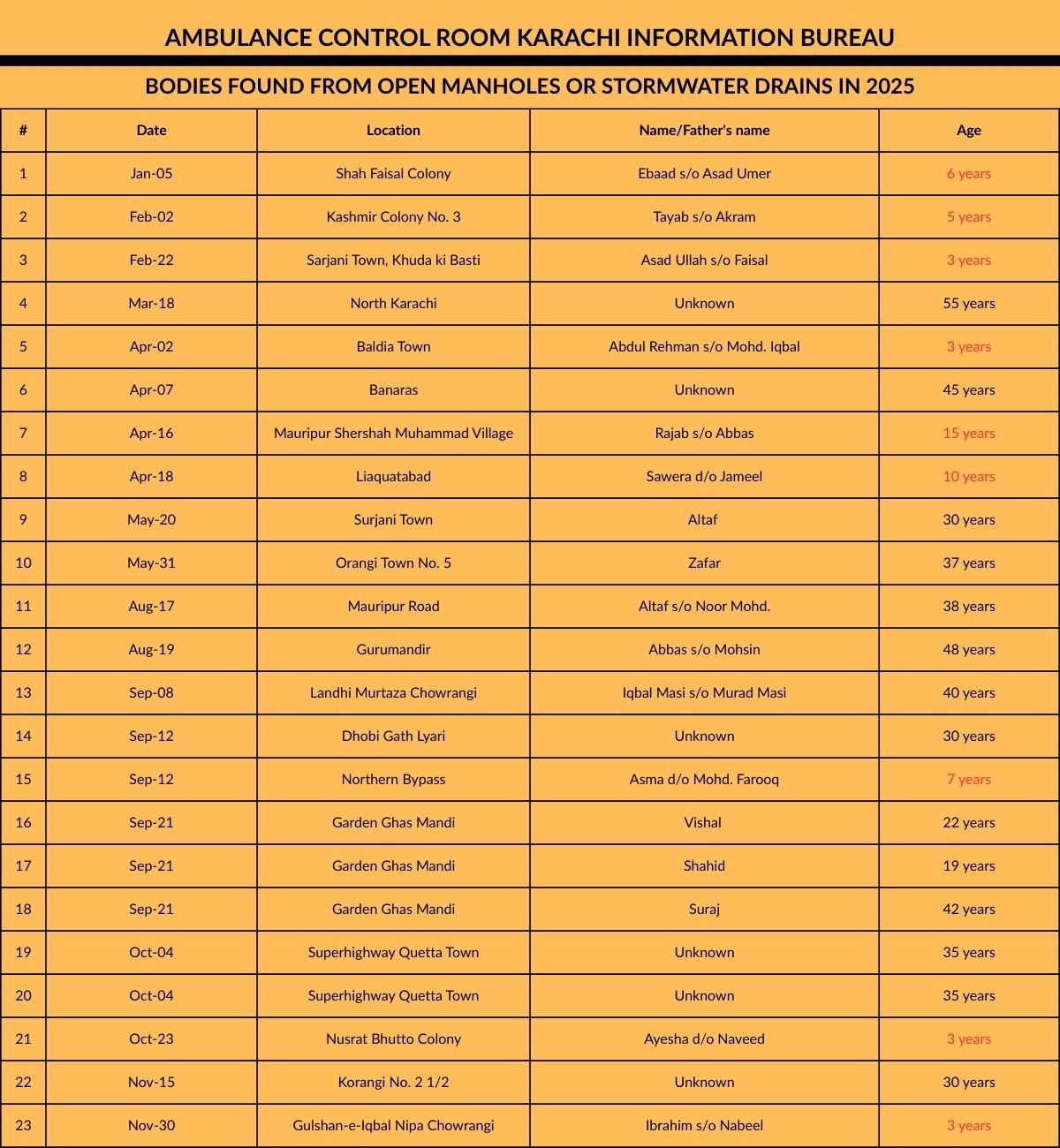

To grasp the sheer, fatal scale of this recent negligence, one only needs to examine the Edhi Foundation’s data on bodies recovered from open manholes or stormwater drains in 2025 and 2024, as documented by their Ambulance Control Room (Tables 1 and 2).

According to the data shared by Muhammad Amin, incharge of Edhi Ambulance Control Room Karachi, 23 citizens lost their lives after falling into open manholes and nullahs across the city between January and November 2025. "At least nine of these were children between the ages of three and 15."

The list includes three-year-old Ibrahim from Gulshan-e-Iqbal, whose death sparked renewed outrage. "In 2024, 21 people died after falling into open manholes and nullahs. Of these, seven were children, including one girl child. Five people died after falling into open manholes, while 16 died, including children, after falling into the nullahs," Amin said.

This rising death toll is a direct consequence of a city spread over 1,300 square miles with a severely fragmented governance structure, where no single entity is willing to take complete responsibility.

The city’s blueprint is divided amongst various federal, military, and provincial agencies.

These agencies include the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), Board of Revenue, Karachi Port Trust (KPT), Defence Housing Authority (DHA), Military Lands and Cantonment Boards, Railways, Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), and others.

Then there are development authorities, both public and private, including Karachi Development Authority (KDA), Malir Development Authority (MDA), and Lyari Development Authority (LDA). In the contest are also the utility companies with their own limitations and boundaries.

Giving the example of K-Electric poles, Sui Southern Gas Company (SSGC) lines, and other hidden utility infrastructure on various roads of the city, Ansari said that all entities were generally helpless.

“If there is a K-Electric pole on the road, the KMC cannot move the pole and has to work around it during road renovations. If they want to work on the manhole, they need to involve the Karachi Water and Sewerage Corporation (KWSC)."

The manhole accident is a result of this responsibility vacuum, where the Red Line BRT construction manager and the KMC are locked in a high-stakes blame game. The KMC inquiry report considers the Red Line’s Project Management Construction Supervision Consultants (PMCSC), responsible for unauthorised excavations and using substandard "temporary" covers that failed to secure the site. On the other hand, the TransKarachi management has fiercely countered these claims, arguing that the incident occurred well outside their active construction corridor and that the manhole in question belongs to a legacy sewerage system for which they have no administrative or maintenance mandate.

This clash of coordinates and contracts ensures that while officials trade allegations, the fundamental duty to protect the public is lost.

It should be noted that until December 7, 2025, the maintenance of manholes in Karachi was a shared responsibility, primarily involving the KMC and the KWSC. However, following the public outcry over the minor’s death, the Murtaza Wahab administration announced a new initiative on December 8, intended to decentralise accountability by empowering local UCs with maintenance responsibilities.

Chairman of UC 2 Hassan Square of Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town Riaz Azhar said, “We’re dealing with 50-year-old lines here. When we dig six feet deep, we learn that the sewer line is turning or is so dilapidated that a simple touch will result in its disintegration,” he explained. He asked where he should begin to fix this extremely dilapidated system inherited from the previous administration.

Unfortunately, the UCs are in the dark when it comes to documented proof of the hidden infrastructure locations. After the November 30 incident and the ensuing chaos, the KMC approved nearly Rs300 million per year (approximately Rs100,000 per month for each of the city’s 246 UCs) for the exclusive maintenance of manhole covers and streetlights.

Azhar called this amount insufficient. “From this Rs100,000/month, we have to deduct 5% Sindh Revenue Board (SRB) taxes, 8% income tax, and around Rs15,000 for the quotations and approval, etc. After all other expenses, we will be left with around Rs40,000/month; an amount which will hardly cover the cost of eight manholes”. Currently, the UCs are using manhole covers made with polyvinyl chloride (PVC) fibre. One 21-inch manhole cover and ring is priced at Rs5,000, whereas a 24-inch cover is priced at Rs5,500.

Architect Ansari noted that this move to PVC is the latest in a failed cycle of material experimentation caused by the state’s inability to regulate the scrap market. He explains that the government originally used cement, then moved to cast iron for higher load-bearing capacity, but these were systematically stolen. Even reinforced cement-steel covers were targeted for their scrap value. Ansari warns that until the government regulates the scrap businesses running in every nook and cranny of the city, even the new PVC covers will remain vulnerable.

The fact that each UC can afford to fix only eight manholes per month underscores the systemic nature of the policy shortfall. The allocation is not a genuine maintenance solution, but a strategic delegation of blame without the necessary resources to prevent the next tragedy.

Zehra, a resident of Shadman Town, described this cycle of operational chaos: “The city is dug up by everyone one by one, and this is not done without a reason”. She points directly to the systemic incentive for neglect: “The outsourcing or contractual system serves everyone by virtue of kickbacks," she said, referencing severe corruption within the ranks of the landowning and development agencies. "Because of this system, the city remains perpetually dysfunctional and a hazard for its residents."

Zehra’s sentiments are echoed by many Karachiites. The general allegations made by people who are in the construction business in the city are that the finances of any development works are divided on a 40:60 formula between the Sindh government and the chosen contractors. If the citizens are lucky, the contractor, after spending 40% on kickbacks, will spend 60% of the approved budget on the much-needed development works. Unlucky citizens get only 40% or lower of the allocated amount spent in their neighbourhood.

A former construction consultant, who has worked with one of the country’s top engineering firms, stated that despite the government receiving millions through initiatives like the Competitive and Livable City of Karachi (CLICK), the ruling party prioritises self-enrichment. This World Bank-funded project aims to improve urban management, yet a majority of the funds are diverted towards kickbacks or vanity projects.

Sharing a personal experience, the construction consultant said, "I could not bring the car to my house because of the broken street. To avoid the inconvenience, I built my street in 4,000 psi (per square inch) strength concrete, but then the new UC chairman demolished and rebuilt the street in really poor concrete mix because he had the power and the money from the government to do so."

This prioritisation of vanity projects over functional utility is evident in major schemes like the BRT system. Architect Ansari questioned the surface-level planning logic for BRT. “The BRT has taken up the majority of a huge road (from Surjani Town to Numaish), while the surrounding plots are being converted to high-density ground plus two-floor portions or multi-storey apartments.” This combination of simultaneously reducing road capacity and encouraging density proves the planning system has catastrophically failed.

This tragedy has proven that cosmetic and incremental maintenance work is ineffective; there is a need for transparency in governance. For this, the creation and implementation of a master plan is essential at the earliest to make Karachi a liveable city. In this liveable city, the government, concerned officials, and private entities should be legally accountable in case of fatalities caused by infrastructure maintenance failures.

The government’s focus should be on civic needs and reforms, instead of elite-oriented and vanity projects. Also, the woefully insufficient budget allocated to UCs for basic maintenance must be immediately reassessed for realism. While systemic reform is a long-term goal, the immediate concern for grieving families, such as Ibrahim’s, is identifying paths for legal recourse.

Lawyer and political activist Jibran Nasir noted that while proving criminal liability is a high bar, civil and constitutional remedies exist. “Primarily, their liability under civil law would be under the Fatal Accidents Act, 1855, where they can claim damages by showing the quantum of loss of emotions and trauma caused, and the future perspective of loss of earnings,” Nasir explained. He also suggests a Constitutional Petition as a means to seek exemplary damages for the violation of fundamental rights.

Regarding criminal charges, Nasir clarified that while terms like Qatl-i-bis-Sabab (causing death through an illegal act) or Qatl-i-Khata (mistaken murder) exist, proving them against the state is difficult without evidence of prior knowledge or specific complaints. “Therefore, I believe their primary liability lies under civil law and public law where they can seek damages,” he concluded.

Andaleeb Rizvi is a journalist and a former staffer at The News. She has editorial expertise on Pakistan’s economy, trade, and urban development, with academic experience in architecture and planning.

Header and thumbnail image by Geo.tv