A new muhajir politics: Leaderless, fragmented, unresolved

For two years now, Meena Bazaar in Karimabad has had a giant ditch dug up on its doorstep. Promised as a kilometre-long underpass (above which is a flyover), construction work has been ongoing for nearly two years, with barely any measurable progress. From Malir to the Quaid’s Mausoleum, a rapid bus service is supposed to run, but for now, motorists taking University Road have been delivered a safari on their daily commute.

The areas for these two projects are dominated by the Muttahida (formerly Muhajir) Qaumi Movement (MQM)-Pakistan, which itself broke apart in the last decade, following the Altaf Hussain-led MQM's formation on the back of a new kind of student politics that gained shape in the 1970s. When the All-Pakistan Muhajir Student Organisation (APMSO) was founded at the University of Karachi in the summer of 1978, it marked an ethnic shift from the right and left-wing student politics that had led to the ouster of General Ayub. Later, General Zia’s ban on student unions in 1984, fearing a similar uprising, only led to the groups being unregulated and much more violent.

An October 1988 Herald article by Zahid Hussain notes that while 14 students had been killed in Karachi between 1977 and 1984, the next four years saw 66 students murdered, the deaths also higher due to guns that had entered the city with the spillover of the Cold War.

That violent brand of politics, however, did not remain limited to university campuses. Instead, it spiralled the entire city into the kind of politics MQM became committed to. A whole generation later, however, new entrants to Karachi’s political scene, such as the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), have reshaped how elections in the city can be contested, and the former has done so far more successfully than the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), despite its long political history in the city.

However, is ethnic politics truly dead? Despite obvious issues in Karachi’s census data and challenges in defining ethnicity, the Muhajir vote still holds significant political sway, largely due to its numerical strength in the city. This is despite an uptick in newly-migrated Sindhi voters, and even a decrease in the Pashtun vote.

Manzil nahin, rehnuma chahiyeh

Major political parties in Pakistan are dynastic, such as the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). There is a tried and tested method of maintaining their power by either passing the torch on to their progeny or one of the alliances through marriage. Similarly, Awami National Party (ANP) remains tethered to its family — Aimal Wali Khan is the great-grandson of Bacha Khan.

MQM and PTI, however, have demonstrated significant sway in Karachi’s recent politics and potential future; they have no hereditary structure in place. Imran’s sons' entering the political landscape in Pakistan is tenuous at best, and a post-Imran PTI doing well seems unlikely.

In the past decade, two realpolitik manoeuvres have taken place in which both PTI and MQM have since been forced to deal with a radical restructuring for political survival. The first was the crackdown against workers loyal to Altaf Hussain, which led to the creation of MQM-Pakistan, a group that disavows any reference to Altaf, and the second was the continued incarceration of Imran and other PTI leaders, which has limited the party’s reach.

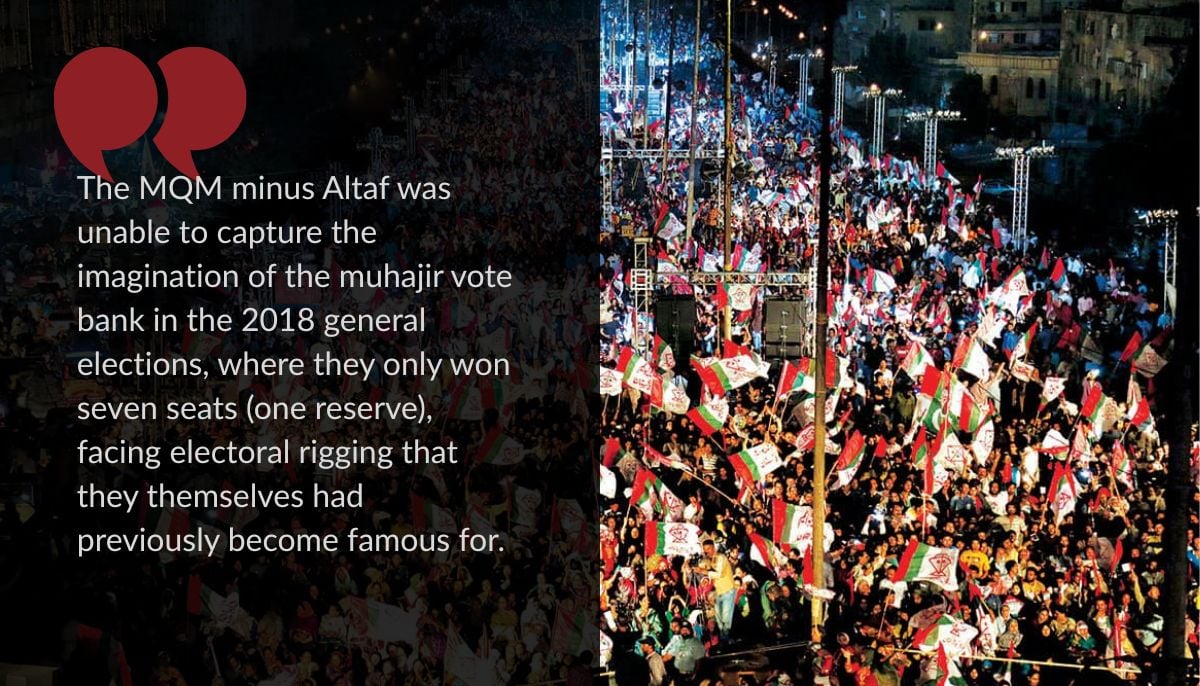

The MQM minus Altaf was unable to capture the imagination of the muhajir vote bank in the 2018 general elections, where they only won seven seats (one reserve), facing electoral rigging that they themselves had previously become famous for. In the city’s new politics by design, then, the PTI, following massive rallies and support, ended up dominating Karachi’s seats in both the provincial and national assembly. To even the casual onlooker, the shift was seismic.

Fast forward to 2023, the MQM-Pakistan found favour with Pakistan’s power brokers, and although on Form-47, MQM-Pakistan has 21 seats in the National Assembly, independent observers maintain that widespread rigging seems to have been the primary reason.

This, however, was not the first time that the MQM had received a nod from Islamabad. Musharraf’s takeover of the country in 1999 protected the MQM and even led to the creation of the City District Government Karachi (CDGK), in which those loyal to the MQM received jobs.

Musharraf’s ouster in 2008, however, then began maligning MQM’s power. Despite a hold on the city’s politics in the 2013 elections — one marred by violence — the movement had begun to dissipate MQM’s control of the city. Altaf’s August 22 speech in 2016 ended with paramilitary forces raiding Nine Zero, MQM’s headquarters, and arresting its leaders. It was almost a precursor to Imran’s arrest in Lahore by the police.

While the PTI struggles with leadership after Imran, the MQM has already become a litmus test, particularly in Karachi. After Altaf and Imran, neither the current MQM nor PTI leadership has produced an heir apparent.

Among political parties in Pakistan that have, to some degree, managed to stay afloat despite a lack of hereditary support is the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), but it has delivered poor electoral results. In Karachi, while it has performed at the union council level, with several members elected, it has so far been unable to do so beyond that.

Whom to speak against?

A callous charade has overtaken the blame game for Karachi’s issues, with the news cycle unfolding as follows: for every bad incident, be it rain, lack of utilities, or even death by criminal negligence, the PPP blames the MQM, which, in turn, pins it on the former, and life returns to normal.

As it stands, the MQM-P and PPP are in a coalition federal government. Outside of flimsy arguments and posturing on traditional and social media, the allies cannot actually spar with each other when it comes to both major and minor administrative problems that Karachi faces today. If Karachiites were to protest, they don’t have a party to mobilise a protest with.

Any cracks within the federal coalition and Karachi once again goes up for grabs, which could potentially spiral into violence. Unfortunately, for Karachiites, this has left the PPP as the sole choice for governance.

The PPP’s political calculus for Karachi has also, for now, determined that the MQM-P is the political group that they would most likely side with. In ethnic terms, they have chosen an Urdu-speaker, Murtaza Wahab, as mayor in an allegedly fraudulent election which saw the PTI team up with JI.

Wahab, however, has now come to only represent failures of the PPP, but behind an ethnic lens. A non-muhajir mayor supported by the PPP might spur resentment amongst Urdu-speaking Karachiites. Therefore, PPP remains committed to a mayor who has become a beta, low-budget version of the kind of projection politics that Shahbaz Sharif began in the late 2000s, and which now his niece Maryam has taken a step further in Punjab.

The idea of muhajir

The idea of a muhajir cannot exist without the idea of Pakistan, and this is precisely why scholars such as Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar have noted in reference to the 1990s operations against Altaf Hussain, that muhajir disillusionment with the idea of Pakistan has been “ironic”, given their contributions in demanding a separate Muslim homeland in South Asia in the first place. Muhajirs felt that the creation of Pakistan was both a political and religious duty.

The fact that an anti-Pakistan sentiment for muhajirs would emerge as early as the 1990s represents, according to Yacoobali, “…one of the most significant ruptures in the narrative of Pakistani nationalism”.

However, more recent work shows that following the 2016 crackdown against MQM workers loyal to Altaf Hussain, is when a new Muhajir politics could emerge. As Tahir Naqvi writes, “…the post-2015 period is precisely the kind of situation that would benefit from a resurgence of ‘muhajir’ exclusivism, and yet such a move has not been made by domestic leaders of the movement.”

However, it is difficult to see how the movement that Naqvi points towards is possible with the present ban on student politics, given APMSO’s role in setting the groundwork for the MQM. While student mobilisation has existed to some degree, the ban on student unions has now lasted well over a generation, which has led to the need for a rethinking of what student politics today could look like, with several left-leaning groups emerging. For any muhajir exclusivism, as Naqvi suggests, an APMSO might be the only vehicle that could deliver.

This ethnic exclusivism, however, is one of two routes a new muhajir politics could take, and is one that continues to term itself a muhajir politics, and essentially rewinds time to launch a new MQM. This further enmeshes the muhajir identity back into the ethnically fuelled politics the country has found itself in.

However, since muhajir-ness can only exist within Pakistan alone, there is then the other option of reimagining if the linguistic group of Urdu-speakers wish to remain muhajir, or develop new ideas for progressive politics. Is Karachi to remain passive, or will it become a hub of progressive political activity once again?

Saeed Husain is an anthropologist and editor at a publication house. He posts on X @saeedhusain72 and can also be reached at [email protected]

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv