Climate-vulnerable Pakistan, measured in disasters, counted in risk

What lies ahead for Pakistan after being ranked 15th most impacted by floods, heat waves, and climate disasters?

Pakistan keeps ending up among the world’s most climate-hit countries, facing floods, heat waves, water shortages, failing crops, and food insecurity, while contributing almost nothing to global emissions, its weak systems and exposed geography leaving millions to live the crisis every year. The country barely emits anything, even less than one percent, yet it keeps getting hit from all sides. Floods, heat, water shortages, food problems keep piling up, while the systems remain weaker than ever. Planning is weak. Governance is patchy. Experts say calling it "highly vulnerable" changes nothing as long as funds, coordination, long-term work is missing.

Otherwise, it's the same story over and over.

The latest Germanwatch report calls for reducing global carbon emissions, increasing adaptation to climate change, and addressing Loss & Damage (L&D). It also focuses on climate justice, calling for a shift in responsibility to those countries that are actually responsible for the climate crisis.

The report draws connections between extreme weather events and climate change and draws reference to the IPCC AR6 report, according to which, "human-caused climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe."

Hammad Naqi Khan, the chief executive officer at the World Wide Fund for Nature-Pakistan (WWF-Pakistan), explains that Pakistan spans arid, semi-arid, and glacial regions, making it naturally prone to climate extremes, heat waves, droughts, floods, and glacial hazards. According to him, the Indus River basin is highly sensitive to variability in monsoon patterns, and our (Pakistan’s) economy is heavily dependent on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture; even slight shifts in rainfall or temperature severely affect crop yields, livestock, and food security.

Khan also lists several factors that are increasing Pakistan’s vulnerability to extreme weather events. “Deforestation, improper land use, and degradation of ecosystems amplify disaster impacts.

"Loss of forests reduces natural flood protection. Shifts in monsoon patterns can cause long dry spells, triggering droughts, or heavy rainfall in short periods, leading to flash floods.

"Despite having a history of recurring climate disasters, we are still not prepared, and we have weak policy implementation, inadequate early warning systems, persistent data gaps in each sector, along with a lack of financing for climate adaptation," he noted.

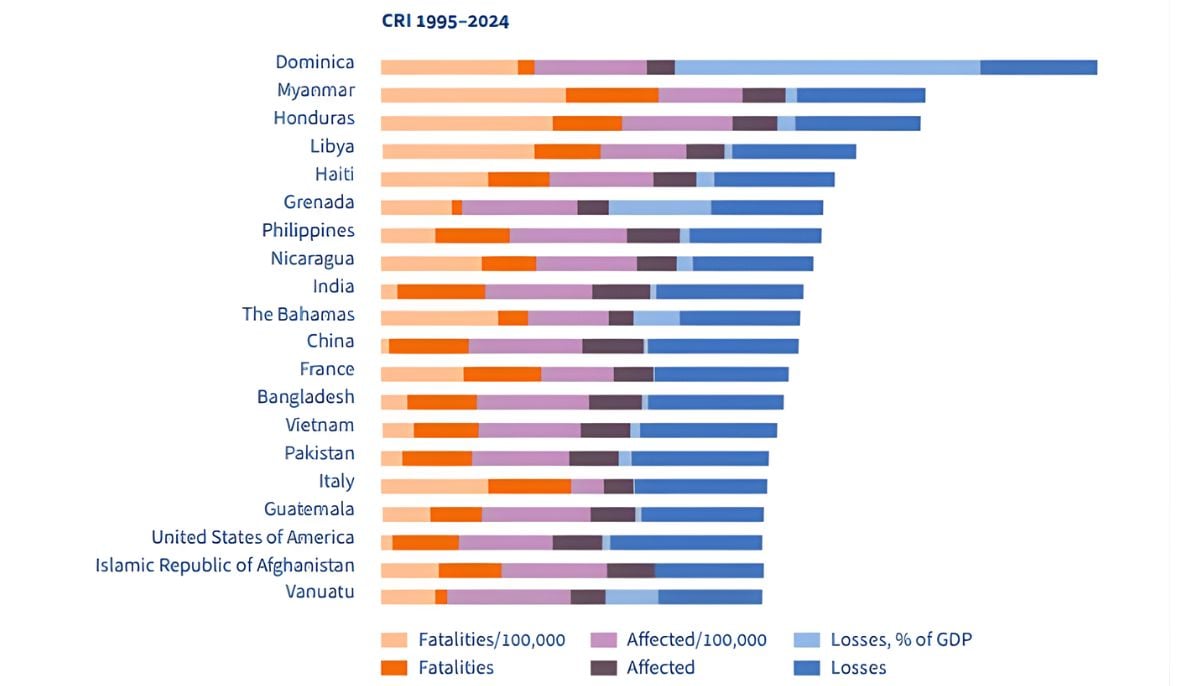

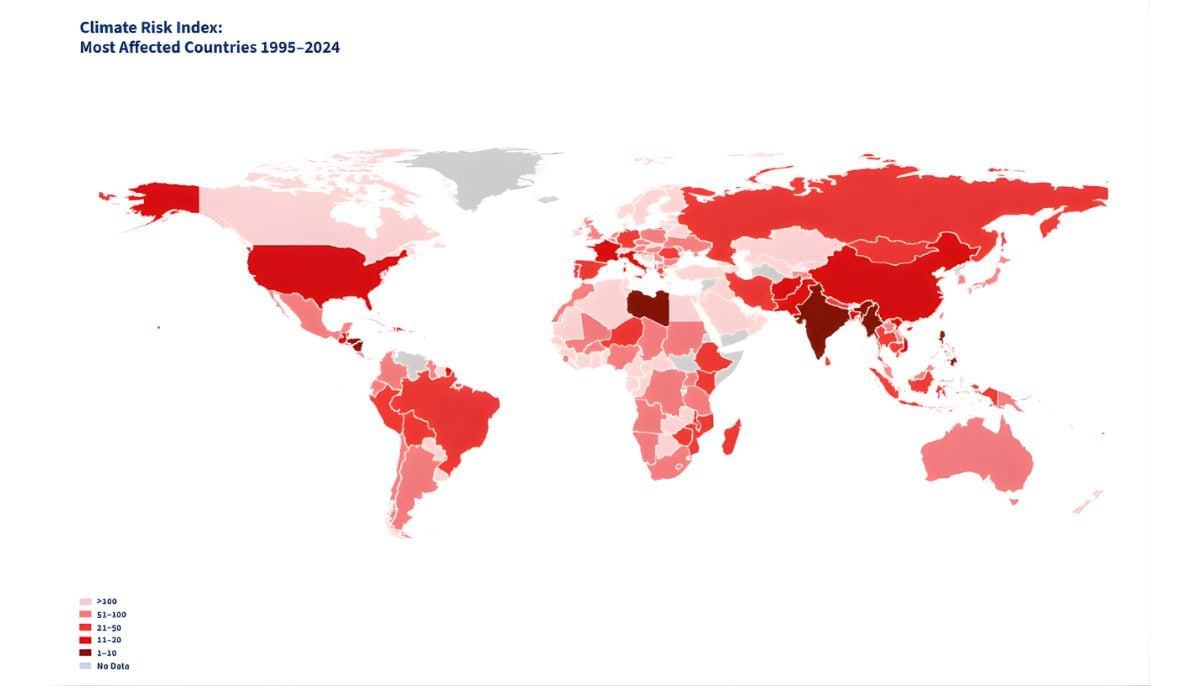

Vera Künzel, one of the co-authors of the Global Climate Risk Index 2026, in this exclusive interview, shares that Pakistan’s 15th position over the 30-year period (1995-2024)is a "very high rank".

"It shows that the country (Pakistan) has been very heavily hit by events like the extraordinary floods in 2022, with more than 33 million people affected, more than 1,700 fatalities, and accumulated damage of nearly $15 billion," said Künzel.

As Pakistan has been consistently ranked by Germanwatch among the most affected countries in the short- and long-term, Künzel clarifies that the CRI cannot measure political actions or similar benchmarks.

According to her, the high affectedness (due to climate change) hints towards the fact that there is a need for better adaptation as well as climate risk management in the country, which is also dependent on (lacking) international support.

Commenting on the report, Khan says Pakistan continues to rank within the top twenty in the long-term CRI, reflecting its high exposure and sensitivity to climate risks.

“However, the long-term index (1995-2024) is influenced by methodological factors, such as multi-decadal averaging, variability in reported data, and comparative differences in event frequency and intensity across countries.

“These elements can affect year-to-year placement and may prevent Pakistan from appearing in the top ten in the long-term aggregation, even though it remains among the most climate-vulnerable countries globally,” he explained.

Outlining the reasons behind Pakistan’s high vulnerability to climate-induced extreme weather events, he says there has always been weak coordination between federal, provincial, and local level governments.

"Multiple plans and legislations like NCCP, Climate Change Act, NDMA, and provincial plans exist, but the roles, budgets, and performance monitoring are fragmented and there is inadequate financing and weak public financial planning.

"Financing for adaptation is not only insufficient but is also often donor-driven rather than budgeted into recurrent public spending.

"The district governments and municipal planners lack the technical skills for the implementation of the existing plans," the WWF official noted.

Izabella Koziell, the deputy director general of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), a regional knowledge centre headquartered in Kathmandu, Nepal, provides several reasons behind the variation in rankings, both in the short-term (2024) and long-term (30-year average):

Exclusion of slow-onset impacts

The Global Climate Risk Index (GCRI) is heavily event-centred, focusing on extreme events/hazards such as floods, droughts, wildfires and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). It fails to account for devastating slow-onset cumulative and irreversible impacts that are pervasive in the HKH, such as glacier shrinking, loss of snowpack, drying of water bodies (springs and kuhls), degradation of rangelands, and reduced sector productivity due to shifting climate patterns.

Data gaps and under-reporting

The index relies on global disaster datasets (like EM-DAT), which suffer from uneven, partial and sometimes delayed reporting, especially in the Global South. Losses from GLOF events, high-mountain flash floods, agricultural losses, and localised impacts often remain undocumented or are reported late. As a result, actual losses in Pakistan and other HKH countries are structurally under-captured, leading to an artificially lower rank.

Dilution of systemic events

The long-term average (30-year signal) can dilute the impact of one or rare but catastrophic events (like Pakistan's 2022 floods). Hence, the short-term rank may shoot up for a given year (e.g., Nepal and Myanmar in 2024), but this signal is lost in the long-term list.

The 'Relative Value' effect

The use of relative indicators (e.g., fatalities/affected people per 100,000 inhabitants) can deflate the overall index value for countries with large national populations (like India, Pakistan) compared to Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which may skew the ranking towards SIDS.

Bias towards well-documented events

The methodology appears to give more weight to sudden, well-documented events (like cyclones) common in coastal areas, while under-capturing multi-hazard, cascading cryosphere-driven disasters common in Pakistan and the HKH (region).

Arbitrary weighting

The choice of the weighting scheme used to construct the index appears arbitrary and not fully transparent, meaning small changes could significantly alter country rankings and credibility.

South Asia’s vulnerability to climate change

Künzel shares that countries like India and Nepal have been ranked in the short- and long-term indexes of Germanwatch this year, which is a warning signal to better prepare in terms of adaptation and climate risk management, and at the same time a call to the international community to increase support for those countries hit hard.

Commenting on South Asia’s vulnerability to climate change, Khan from WWF-Pakistan says that “densely populated, low-lying, agrarian economies with weak infrastructure, unstable political situation, and limited adaptive capacity are bearing the brunt of escalating climate risks. Countries like India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have implemented market reforms, opened up trade, improved business regulations, or strengthened specific sectors (information technology in India, garments in Bangladesh).”

Knowledge sharing in the Global South

Izabella Koziell, from ICIMOD, suggests the following:

Focus beyond extreme events

All Regional Member Countries(RMCs), including Pakistan, must acknowledge that relying on national-level statistics for only extreme events is a crude indicator at best. The focus must be widened to systematically assess them (extreme weather events).

Develop robust vulnerability assessment

Pakistan can learn from the shared regional experience that there is an urgent need for developing a robust vulnerability assessment mechanism at the country level. As Nepal's experience with the 2024 floods clearly showed, low adaptive capacity and institutional readiness in dealing with extreme events is a strong marker of high vulnerability.

Strengthen data and reporting

All regional member countries must prioritize improving national disaster documentation and data quality, especially for sub-national and sectoral losses, and ensurethese are accurately captured in international datasets like EM-DAT. This is essential to prevent the country's climate-related loss and damage from being under-captured or under-reported.

Regional collaboration is essential

Collaboration among HKH regional member countries is vital, especially regarding shared threats like GLOF risk reduction and other complex, cascading cryosphere-related hazards. Pakistan, Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Afghanistan benefit from similar geography and hydrology, making cooperation not optional but essential.

Move toward multi-hazard and multi-indicator risk monitoring

For Pakistan and all HKH countries, the goal is to enhance systemic resilience by moving towards a more sophisticated, multi-hazard, multi-indicator methodology that fully accounts for the unique, cascading, and slow-onset risks characteristic of our mountain systems.

Khan, on the other hand, said that Bangladesh was improving its climate resilience by establishing robust cyclone early warning systems and investing heavily in community preparedness and shelter.”

“We also need to work on a bottom-up approach, just like Nepal is with a Local Adaptation Plan for Action framework. It is inclusive, responsive, and flexible, and lets local communities identify their vulnerabilities and choose adaptation actions that make sense for them. Pakistan should also invest in technology innovation, digitisation, and cross-border collaboration for better climate resilience.

"Nepal and India are working together on a community-based flood early warning system on the Karnali river system (in the Terai region). This system uses solar-powered digital river monitoring system, shares data in real-time, and sends SMS alerts to vulnerable communities. This kind of cooperation is critical because many river systems across national borders; while climate change (e.g., glacier melt) makes flood risk more dangerous,” adds Khan.

The way forward

Künzel suggests that the climate vulnerable countries in South Asia should push for closing the global ambition gaps by pushing for drastic emission reductions, acceleration of adaptation efforts, and effective solutions to address loss and damage – and for all of this: adequate climate finance must be provided (and drastically increased, especially for adaptation and L&D).

According to Künzel, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion supports this point and clarifies that states have binding legal duties to prevent and address the harmful effects of climate change – including stronger mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage actions and provision of climate finance.”

Whereas, Khan suggests inclusion of a separate climate fund (including mitigation and adaptation funds) in the provincial budget is necessary for robust implementation of the climate policies and plans.

“There is a need to establish functional regional climate service centres (one per province/zone) to provide training, technical support, and project design, while it’s imperative to upgrade network hydro meteorological stations, ensure real-time river gauge data is public, and strengthen flood forecasting models.

“We must also build a national climate information platform (open data) and mandate its use for public procurement and infrastructure siting and building codes also need to be updated and their enforcement (flood-resistant standards for roads, schools, hospitals) should be ensured.

“Investments should be made in planned resettlement programmes accompanied by livelihood support for affected communities,” Khan added.

He noted that WWF-Pakistan was tackling the climate crisis through a mix of large-scale ecosystem programmes, community-level action, and private-sector engagement.

“Initiatives like the Recharge Pakistan project aim to restore 14,215 hectares of wetlands and forests,” Khan said. “The WRAP (Water Resource Accountability in Pakistan) programme is strengthening water governance and piloting nature-based solutions across 17 districts.”

He further said that WWF-Pakistan was also scaling up regenerative agriculture and running the Green Office Initiative to promote sustainability in the corporate sector. “Through the ILES (International Labour and Environmental Standards) programme, we are working to reduce emissions, energy use, and water consumption in leather and textile SMEs,” Khan added.

The Germanwatch report has highlighted the vulnerability of the world, especially the Global South, to extreme weather events and how they are exacerbated due to climate change. For Pakistan, it is a matter of survival as the communities in the fragile ecological areas are vulnerable to adverse climatic impacts such as floods, GLOFs, cloudbursts, and other extreme events. It is in the best interest of the HKH-member countries to collaborate and share knowledge and technology to address the biggest challenge of our time – climate change.

Syed Muhammad Abubakar is an international award-winning environmental journalist, a Chevening and IVLP Alumni. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Communication at George Mason University, US. He tweets @SyedMAbubakar and can be reached via [email protected]

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv