Fatal measles complication more common than thought: US study

"We have to vaccinate our kids or we are going to suffer the consequences"

October 29, 2016

A deadly complication of measles in young children that strikes years after infection may be more common than previously thought, according to a study presented on Friday that stressed the importance of vaccinations against the highly contagious disease.

The risk of acquiring the always fatal neurological disorder, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), was believed to be about 1-in-1,700, based on an earlier German study of children under five years of age infected with measles.

The new research, looking at children who got measles during a large California outbreak around 1990, found the rate of SSPE to be 1-in-1,387 for those infected before the age of five. It rose to about 1-in-600 for babies infected before their first birthday.

"That is a very frightening surprise," said Dr. James Cherry, a research professor in pediatric infectious diseases at UCLA, who was part of the study team.

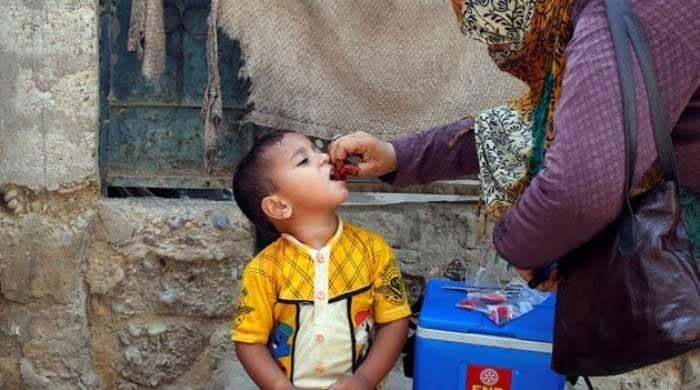

"The answer is good public health. You need to vaccinate everybody and create herd immunity so that you protect those most vulnerable to measles and those at greatest risk of SSPE," Cherry said in a telephone interview.

Herd immunity would protect infants too young to get the measles vaccine and people with compromised immune systems ineligible for vaccination.

The average age of SSPE diagnosis was 12, but the range was from three to 35, researchers said.

The findings were presented at an infectious disease meeting in New Orleans known as ID Week.

The presentation included an account of a mother whose five-month-old got measles after a trip to Disneyland during an outbreak last year.

"She says 'Now I have to worry about this for the next 10 years.' It's kind of sobering," Cherry said.

Merck & Co and GlaxoSmithKline are among the main manufacturers of measles vaccines.

Researchers hope the data will raise alarms with parents who refuse vaccines for their children, despite science confirming their safety and benefits.

They also cautioned parents about traveling with unprotected children to countries where measles is endemic.

"No child should go to Europe or the Philippines who hasn't had two doses of measles vaccine. It's just too risky," Cherry said.

Dr. Peter Hotez, an infectious disease expert from Houston who was not involved in the study, said a growing anti-vaccination movement in Texas could lead to measles outbreaks there.

"Once vaccination coverage rates start going below 90 to 95 percent, because it's so highly infectious, that's when you start to see measles. It's going to come back and it's not a benign disease," Hotez said.

Even without SSPE, measles can kill or cause encephalitis.

"We have to vaccinate our kids or we are going to suffer the consequences," Hotez warned.