Quick takes: Does Pakistan need a presidential system?

Geo.tv ask political wonks whether an over-centralised presidential system would work in today’s Pakistan

April 22, 2019

It is a debate that seems to be getting louder by the week. No one knows where the murmur first began or who originally suggested that Pakistan switch over from a parliamentary form of government to a presidential one. But the dispute is raging on. Last week, Pakistan Peoples Party’s Asif Ali Zardari promised to resist any attempts to bring in a presidential system. Separately, those aligned with the ruling party are drawing up its merits to argue that the parliamentary regime has failed.

Since its creation, Pakistan has experimented with both forms of government.

Geo.tv ask political wonks whether an over-centralised presidential system would work in today’s Pakistan:

“Pakistan has a troubled history and legacy of four ‘presidents’”

A presidential system, in theory, entails separation of powers and built-in checks on the exercise of executive power. The French and the US systems have strong checks on the authority of the presidents that ensure a separation of powers between the legislative, executive and judicial arms of the government. But in Pakistan’s case, there is a troubled history and legacy of four ‘presidents’, who enjoyed overwhelming power over other branches of the government. There were assemblies under Ayub Khan, Zia-ul-Haq, Pervez Musharraf but they only acted as rubber stamp institutions. Such a system continued the colonial tendencies of centralised political power; and was resisted by federating units that felt marginal to central authority exercised by civil-military bureaucracy. Which is why the 18th Amendment was a historic moment when this centralisation was done away with to a great extent. An underlying theme of Pakistan’s history has been a dysfunctional federal system that was finally addressed by 18th amendment after six decades of the country’s existence. A reversal of this process will harm the workability of the federation, and revive the fault lines that the past decade has tried to address and repair.

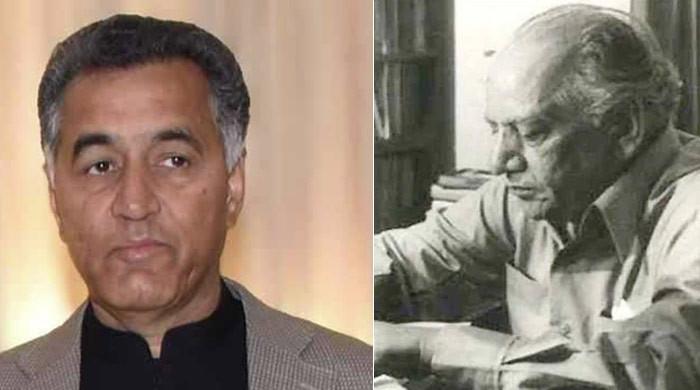

Raza Ahmad Rumi is a policy analyst and an author.

“A country of 200 million is not a lab experiment”

Isn’t it odd that there is still a debate on whether Pakistan should have a parliamentary or presidential form of government nearly seventy years after the country’s inception? That should be the real question and not whether which system of governance would suit the country. It isn’t as if there haven’t been several experiments already. We struggled to draft a constitution, we’ve swung between indirect elections and universal suffrage, parliamentary and presidential, non-party based elections to multi-party, civilian governments and military governments and the various shades in between. The time for experiments should be over. Another experiment will not yield stability, as the advocates of a presidential system would have us believe. The notion of a strong president above the petty concerns of constituency politics, and separate from the messy business of legislation is romantic at best, dangerous at worst. The need right now is stability, for political parties to work together on common national issues and parliament to be given its due importance. A country of 200 million is not a lab experiment. Given the legal and historical precedents weighed in favour of a parliamentary system, it should be time to put away the Bunsen burners and white coats.

Amber Rahim Shami is a journalist and TV host

“A presidential system isn’t a one-man authoritarian rule”

Those propagating the idea of a presidential system do not actually know what constitutes a real presidential system. For most of this ignorant lot, a presidential system basically translates into a one-man authoritarian rule, which isn’t really what a presidential system is. In the United States, the presidential regime is democratic due to the appropriate checks and balances on the head of the state. I wish people read more before campaigning for a presidential system and if they just want a one-man rule, then they should call it what it really is: authoritarian regime and/or dictatorship.

Mehmal Sarfraz is a journalist and political analyst

“The title of a system is irrelevant”

Sustenance, success or the failure of a system rests on the people who drive it. All political governance dispensations — parliamentary (such as UK, Germany, India) or presidential (French, Turkish or American) or autocratic (Russia, Singapore) or one-party ( China, Taiwan) — draw their strengths from the particular socio-political context.

At the same time, exploiting that context effectively and to the advantage of the masses, depends on the quality and intent of the drivers ie prime minister and or the president. Its these key stakeholders on top who — through their acts — define the virtues of a system. It is, for example, Lee Kwan Yew’s sheer commitment to development, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s vision for economic progress and the President of China Xi Jinping’s absolute contempt for corrupt practices of government and party officials that have seen Singapore, Turkey and China rise to phenomenal levels of economic stability.

Presidential systems in Brazil or South Korea, on the other hand, have seen quite a turmoil in the last decade and a half, with at least two former presidents arraigned and convicted for corruption. Lula da Silva is serving a 25-year jail sentence for corruption. His successor Dilma Rousseff was also impeached and sentenced in 2016 on similar charges.

In South Korea, former President Lee Myung-Bak was sentenced to 15 years in prison for corruption and also fined $11.5 million, in a string of similar convictions of former presidents.

Parliamentary democracy in India, on the other hand, has hardly stemmed the abuse of the system by the powerful nexus between politicians and businesses — giving birth to several financial scandals. Neither has it dented the dehumanising caste system nor did it help ameliorate the plight of the over 250 million Dalits (the untouchables).

Germany and France, on the other hand, represent two contrasting, though excellent European examples of how law-based mechanisms and their drivers can function regardless of whether the political system is called parliamentary or presidential.

I would therefore argue that the title of a system is irrelevant. It all depends on the will, commitment and determination of the key drivers of the system to make it virtuous or otherwise.

Imtiaz Gul is an author and the executive director of the Center for Research and Security Studies