They don’t make good 'dramey' anymore!

Is it time for national television channels to acknowledge public discourse and make better content?

It is a commonly held belief among national television viewers that the plots, characters, and overall structure of our shows have declined greatly.

One frequently comes across nostalgic posts making rounds on social media, glorifying the quality of television productions in the 1980s, and lamenting the lack of finesse in shows that are currently being aired.

The same sentiments are shared during leisurely conversations at home or in workplaces. While dealing with an increasingly grim economic and political scenario, the average Pakistani probably looks for and often fails to find lighthearted, but wholesome entertainment.

From the very beginning, the broad mission of state-run Pakistan Television (PTV) was education. Traditionally, PTV content has been divided into four categories: news, sports, entertainment, and infotainment.

Children's programmes, documentaries, and serialised Urdu dramas/plays were grouped together as "infotainment" genres, with the intention of advancing educational goals while passing as entertainment.

The advancement of technology now provides unlimited access to global media, and the emergence of innumerable private channels on the national scene provides a plethora of choices to the average audience.

Cultural and religious restrictions make the television the most popular form of entertainment in the country. Moreover, religious and educational regressions in Pakistan have resulted in increased restrictions for women. For an average middle- or lower-middle-class woman, watching television shows is one of the very few leisure activities that can be pursued within their domestic spaces.

Largely known as dramey, a term that combines the English word drama with an Urdu suffix to make it plural, provides women with a window into the world they may never get to experience on their own.

Apart from escape, dramey also creates a feminine-friendly space that facilitates communication among women, helping them negotiate their sociocultural identities.

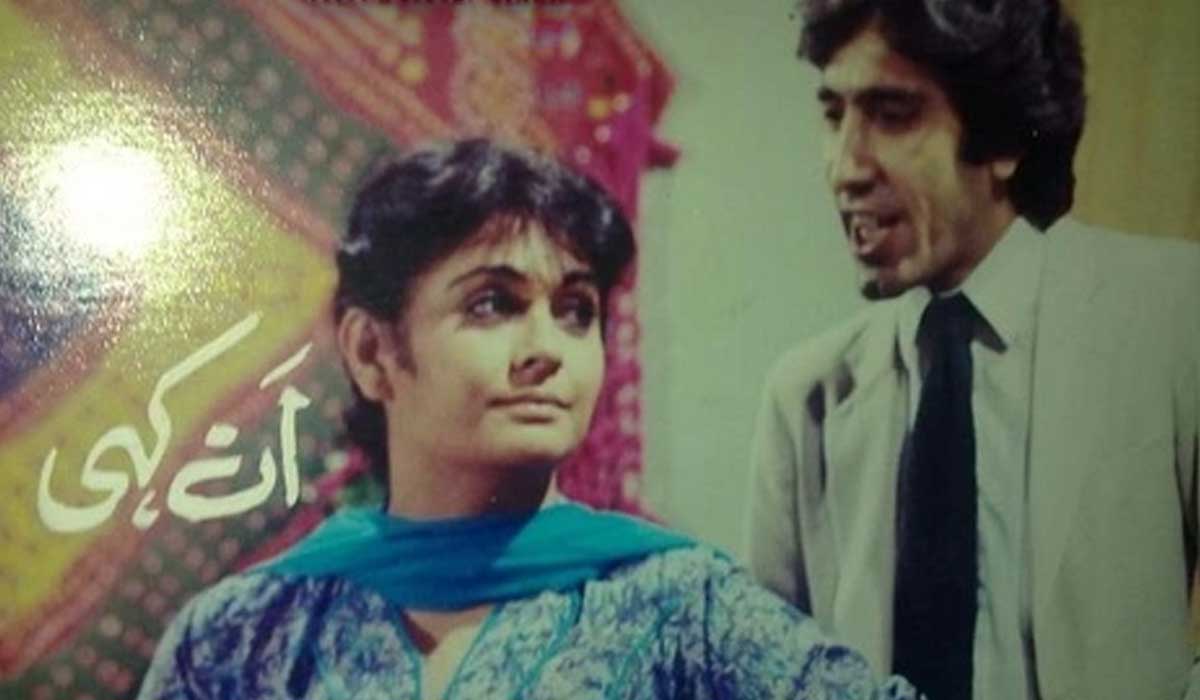

When people talk about past dramas on PTV, they mostly mean television shows by the playwright Haseena Moin. Moin became famous for her brand of social comedies, which featured courageous and witty young women. Her characters and the actors playing them both gained immense popularity and are still considered the hallmarks of grace and an in-depth portrayal of strong emotions.

Talking to Shuchi Kothari, Moin shared how she was requested by PTV to write light comedy serials and how she added tragic moments in the scripts that never made the entire show “weepie-washie.” She believed in showing role models for women, which may not be close enough to the lived reality of women, but not far away to be simply unbelievable or crude.

Moin said, “I created the bold woman character as a counterpoint to all male writers who were showing women as a miserable victim, crushed by the system, eternally self-sacrificing, nurturing, serving her husband even though he visited prostitutes. Oh, it was so degrading! I like writing rebellious characters, and I keep repeating them so that there is an impact. The only thing is, my mode is comic and my words are never harsh. During many interviews, I have been asked why I show strong women characters. It annoys me. Do they ask male writers, why they show strong male characters?”

In a very cyclical movement, dramey have now gone back to what they used to be before writers like Moin brought about a change that still remains in public memory.

When we look at the most popular television shows from the last five years, we see a pattern that is very different from the Moin brand.

New episodes of a minimum of two serialised shows aired daily on more than 30 private entertainment channels. These series can be divided into three main categories based on the three major time slots.

Social tragedies that follow the miserable married lives of Pakistani women are aired between 7pm and 8pm. These stories emphasise that young married women must sacrifice their egos and act as a binding force to keep all relatives together with love in their joint-family units.

Facing mental and physical abuse from mothers-in-law, and tolerating the unfaithfulness or greed of their husbands, female lead characters in such dramey come out victorious in a style that aligns perfectly with our conservative patriarchal society.

One-hour shows aired from 9pm-10pm mostly focus on love triangles in an urban or feudal elite class setting. Primetime shows aired at 8pm get the most publicity on socials written by renowned playwrights, produced with relatively large budgets and include popular actors.

Primetime dramas have more freedom of experimentation and margins to play with set tropes in all genres. Playwrights bring forth issues such as women’s empowerment, sexual abuse, gender-based discrimination, and child labour, and sometimes even dare to question regressive religious and social beliefs.

However, a sudden spike in “slapping scenes” has occurred over the last couple of years. Macho male leads are seen slapping heroines because of their "inappropriate behaviour", with sensational music playing in the background. Frequently, older, and toxic female characters also slap the heroines, pull their hair, and drag them across the floor.

All acts of violence, redundant plots, and stereotypes on the television screen end up conveying a positive social message, which is mostly abrupt and unimpactful.

However, producers and directors continue to struggle to crack the 1980s glory code that Moin and her contemporaries did so successfully for national television viewers. The new trend of social romantic comedies, highlighting halal romance between cousins or neighbours, is a step in this direction as well.

These comedies are broadcast daily during Ramadan and have a seasonal finale on Eid. Ramadan romcoms (romantic comedies) have become a subgenre in every sense of the word, but they still cannot come close to being good dramey in public discourse.

More solid attempts have been made to adapt the Moin brand in a recent show wherein eminent actors like Sajal Ali and Vaneeza Ahmed play the lead roles of strong, witty, independent, and very relatable women.

Social media posts immediately reflect each positive attempt of this type.

Moral of the story

Pakistani viewers of television shows are not simple; ready to swallow crying heroines, macho-looking slapping heroes, or problematic love stories.

We deserve to have strong female lead characters, kind men, and plots that move beyond the issues of matrimonial bliss, unfaithful husbands, and adulterous house assistance.

Production houses work with budget constraints and socio-religious censorship, but PTV’s glory days of infotainment have demonstrated that despite all the restrictions, there is still room to manoeuvre.

Perhaps it is time for national television channels to acknowledge the public discourse on social media sites, work on formulating new strategies, and aim to produce good dramas.

Javaria Farooqui is an assistant professor at the department of humanities and social sciences at COMSATS University Lahore. She is an ardent drama enthusiast and has a PhD in popular culture from the University of Tasmania (Australia). She tweets @JavariaFarooqui

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv editorial policy.