Sticking their long necks out, 240m years old sea reptiles were mostly beheaded

The two fossils had bite marks on them with one having a mark on the broken neck point

June 20, 2023

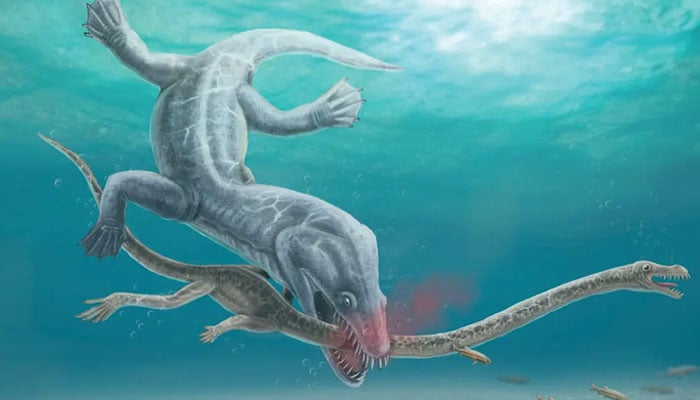

Experts have found fossils of a long-necked sea species — that existed 240 million years ago — revealing that the creatures were easily killed by other predators, proving their earlier theory about their vulnerability, Independent reported.

The scientists corroborated their theory by finding evidence from the fossils that they were decapitated through a brutal bite by predators.

The bite marks on the necks of two Triassic species of Tanystropheus — a prehistoric and distantly-related to crocodiles, birds and dinosaurs — were analysed by researchers, including experts from the State Museum of Natural History in Germany’s Stuttgart.

Their necks were said to be made of 13 extremely elongated vertebrae, strut-like ribs and stiffened necks and waited to ambush their prey.

However, the study has also found that marine reptiles also took advantage of their long necks.

The two fossils had bite marks on them with one having a mark on the broken neck point.

“Paleontologists speculated that these long necks formed an obvious weak spot for predation, as was already vividly depicted almost 200 years ago in a famous painting by Henry de la Beche from 1830,” said study co-author Stephan Spiekman.

“Nevertheless, there was no evidence of decapitation – or any other sort of attack targeting the neck — known from the abundant fossil record of long-necked marine reptiles until our present study on these two specimens of Tanystropheus," Dr Spiekman said.

Prior to the new findings, scientists knew two species of Tanystropheus that lived in a similar environment. One was about a metre and a half in length, which likely fed on soft-shelled animals and the other was much larger up to six metres, which fed on fish and squid.

Researchers substantiated that Tanystropheus likely spent most of its time in the water, by observing their skull.

Two fossil specimens of these species also had necks that ended "abruptly" — leading to speculation that they were bitten off.

"Something that caught our attention is that the skull and portion of the neck preserved are undisturbed, only showing some disarticulation due to the typical decay of a carcass in a quiet environment,” said Eudald Mujal, another author of the study."

"Only the neck and head are preserved; there is no evidence whatsoever of the rest of the animals. The necks end abruptly, indicating they were completely severed by another animal during a particularly violent event, as the presence of tooth traces evinces," Dr Mujal said.

Scientists suspect that the head and neck of these species "were clearly not fed on by the predator".

Scientists believed that the predators focused on meatier parts of the body.

"Taken together, these factors make it most likely that both individuals were decapitated during the hunt and not scavenged, although scavenging can never be fully excluded in fossils that are this old," Dr Mujal concluded.

"In a very broad sense, our research once again shows that evolution is a game of trade-offs," Dr Spiekman said.