Explainer: Will Pakistan's eviction of illegal Afghans help reduce terrorism?

The government’s recent decree demanding the departure of undocumented foreign residents, whether voluntarily or by force, by October 31, has ignited intense debates. This move has raised crucial questions: Why has the government chosen this moment? Who does this policy precisely target — is it limited to Afghan refugees, or does it apply to all undocumented and stateless communities, including Bengalis and Rohingyas?

Various doubts surround the accuracy of refugee statistics, the government's logistical capacity to enforce this policy within the given timeframe, and its ability to handle the deportation of such a substantial number of people.

Geo.tv talked to a diverse range of government and law enforcement officials, experts, and political leaders — both on and off the record — with the aim of unravelling the complexities shrouding this government policy.

Why is the government taking this action now?

Pakistan had previously announced plans to facilitate the return of Afghan refugees over the past few years. Repatriating Afghan refugees was also one of the 20 objectives outlined in the National Action Plan (NAP), a counter-terrorism policy adopted by the government in January 2015 after Taliban militants martyred over 150 schoolchildren in Peshawar in December 2014.

However, the recent announcement is closely tied to the escalating violence in the country, particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces, and the growing tension between the Pakistani government and the Taliban administration in Kabul, according to experts and officials.

Pakistan had hoped that the Taliban's control in Kabul would lead to an end to sanctuaries for the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a group accused of launching attacks in Pakistan from bases within Afghanistan. Unfortunately, the opposite happened. The new rulers released hundreds of TTP militants from Afghan prisons and armed them with weapons left behind by the US, leading to a sharp increase in terror attacks within Pakistan. Despite continuous pleas from Islamabad, the Taliban has denied harbouring such groups.

Additionally, the Taliban's escalated operations against Daesh in Afghanistan have forced the transnational militant group's regional affiliate to relocate to Pakistan, resulting in a surge in their attacks within the country.

According to a recent report by the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), more than 700 security forces and civilians have been martyred in militant attacks in the first nine months of the year.

Sarfraz Bugti, the caretaker interior minister, said that Pakistan's crackdown on illegal Afghan immigrants is necessary because Afghan nationals have carried out 14 out of 24 suicide bombings in Pakistan this year, and eight of the 11 militants involved in recent attacks on two Pakistani military installations were Afghans.

Experts argue that venting frustration over the Taliban regime's lack of cooperation against TTP on Afghan refugees is counterproductive. "It will only strengthen the Taliban administration's stance," said Abdul Basit, a senior research fellow at the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research in Singapore.

"If Pakistan insists that 14 Afghans were behind suicide attacks this year, retaliatory actions may escalate the situation further. This won't solve the terrorism problem,” Basit told Geo.tv.

How many Afghans live in Pakistan?

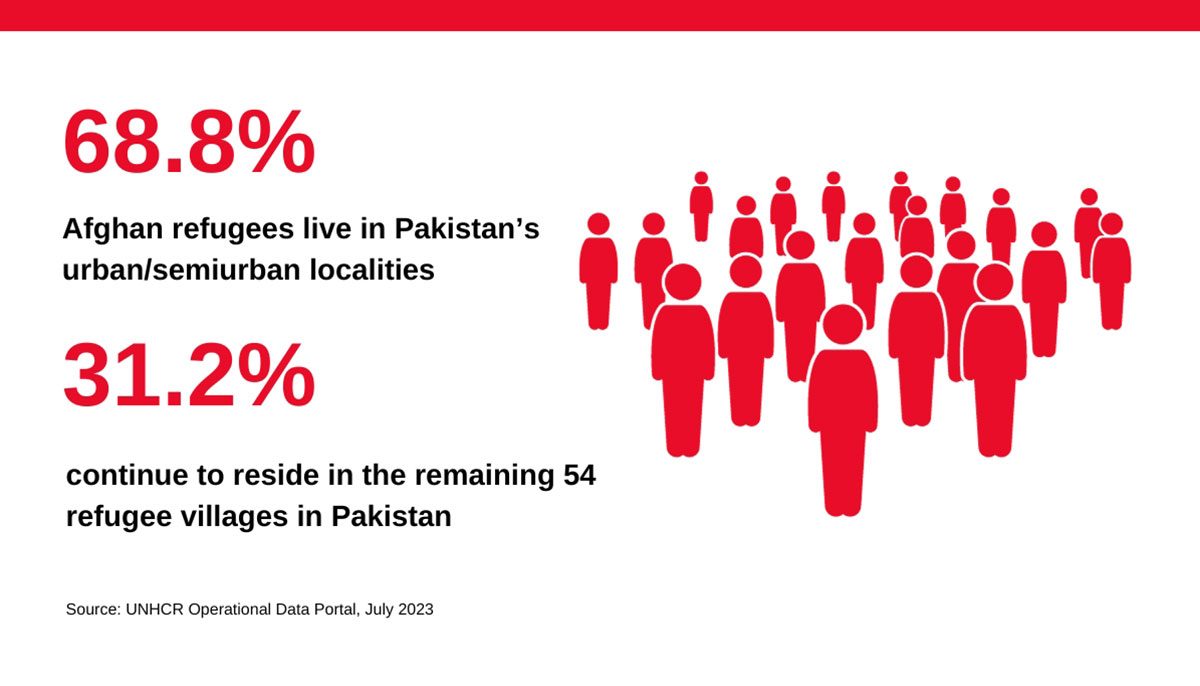

Pakistan has hosted millions of Afghan refugees since the Soviet Union’s invasion in 1979. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) data, approximately 1.33 million registered refugees hold Proof of Registration (PoR) cards, and 840,000 possess Afghan citizenship cards.

The majority of them reside in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (52%), followed by Balochistan (24.1%), Punjab (14.3%), Sindh (5.4%, mainly in Karachi), and Islamabad (3.1%).

However, these documents provide only temporary justification for residing in Pakistan and do not grant refugees access to essential services such as education, healthcare, or the ability to open bank accounts.

Although accurate data is scarce due to Pakistan's census methodology not accounting for aliens, the government estimates that roughly 1.7 million Afghans reside in the country without legal status.

Following the fall of Kabul, 600,000 refugees, including former Afghan security personnel, journalists, and activists, sought refuge in Pakistan, waiting for asylum visas and resettlement in Western countries.

Pakistan’s changing Afghan refugee policy

Pakistan has not signed the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. Despite not being bound by international conventions, Pakistan has a deep-rooted history of supporting Afghan Mujahideen groups during the Soviet invasion and the subsequent Afghan civil war, hosting Afghan refugees and often regarding them as "brothers in faith" and "holy warriors."

Soon after the Soviet invasion, numerous Afghan Mujahideen factions found refuge in Pakistan, establishing bases with Islamabad's assistance. Islamabad united certain Mujahideen groups, under the platform of ‘Peshawar Seven.’

Following the US overthrow of the Taliban regime in 2001 after the 9/11 attacks, many Taliban leaders sought refuge in various parts of Pakistan, a trend that persisted until August 2021 when the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan and formed its government in Kabul.

Experts observed that in the early 2000s, Pakistan adopted a "refugees are no more welcome" policy. However, this stance became more stringent in the wake of Pakistan's military operation Zarb-e-Azb in 2014, which forced groups like the TTP and other militants to relocate to Afghanistan. Since then, TTP began carrying out attacks inside Pakistan from their sanctuaries in Afghanistan.

Why did the past crackdown on Afghan refugees fail?

Pakistan has conducted similar operations at various scales in the past, but they have had limited success.

A major crackdown occurred in late 2016 following terror attacks by the TTP. Approximately 600,000 Afghans, including 370,000 registered refugees and 230,000 undocumented Afghans, left Pakistan because of the crackdown, according to a 2017 Human Rights Watch report. The report characterised Pakistan's actions as the world's largest unlawful mass forced return of refugees in recent times.

However, a significant number of Afghans remained in the country or returned shortly after, showcasing the challenges and constraints faced by the government in repatriating them.

“In 2016, around 5,000 Afghans were arrested and forcibly deported from Karachi," said an elder from Karachi's Sohrab Goth neighbourhood.

"When the crackdown ceased, most of them returned. Many were youths born in Karachi, unfamiliar with Afghanistan and lacking experience of living in the war-torn country."

But Afghan refugee leaders conceded that this time, the crackdown appears to be more stringent and unforgiving.

"If they no longer want us here, we request a timeframe of at least six months to a year, considering the decades the people have spent here building their careers and businesses. How can they uproot everything in such a short period?” the elder told Geo.tv.

How Taliban are reacting?

The Taliban leadership in Kabul has reacted strongly to Pakistan's decision to expel Afghan refugees by October 31, terming it "unjust" and "unacceptable."

“This is an unjust decision and an unfair decision,” said Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, the Taliban administration’s acting Minister of Defence.

“We ask Pakistan’s citizens, its religious clerics, and political elders, to stop these officials who are committing this kind of terror and cruelty to Afghans,” said Yaqoob, who is the son of Taliban movement founder Mullah Muhamamd Omar.

However, a former Afghan government official currently in Islamabad awaiting asylum in a Western country said that the Taliban administration does not care about the problems of refugees.

He suggested that Pakistan's move was aimed at pressuring the Taliban. “But Taliban rulers appear indifferent as they believe they ousted the United States through their negotiations and military efforts, with refugees playing no significant role in it,” he said.

Does Pakistan have the ability and capacity to deport a significant number of Afghans?

The Pakistani government, although yet to reveal the deportation strategy, has established a task force to oversee the crackdown, according to sources in various law enforcement agencies.

"This crackdown is a clear message to Afghan refugees that Pakistan may not be their permanent home," said an intelligence official closely involved in the matter.

The official added that identifying and deporting undocumented refugees is a challenging task, requiring substantial resources, manpower, and intelligence coordination.

“Completing this task in less than a month is nearly impossible,” the spy operative said, and emphasised that with the recent intensified crackdown, including increased detentions and house-to-house searches, Pakistan could potentially force and deport approximately 200,000 Afghans within a few months.

Is a new Afghan refugee policy needed?

Some experts and law enforcement officials argue that refugees worldwide can pose challenges for host countries.

“Even advanced regions like Europe are becoming cautious about migrants and asylum seekers, limiting entry and support,” the intelligence official said.

However, attributing all of Pakistan's issues – including militancy, crime, weapons, and drugs – solely to Afghan refugees is inaccurate, he said.

“The presence of millions of unregistered Afghan refugees poses a significant security challenge for the country,” the intelligence official added.

He stressed the need for a comprehensive policy involving all stakeholders, including the military, political parties, experts, and civil society groups, considering the ground realities in the absence of a functioning parliament due to the caretaker government setup.

What other stateless communities are thinking?

The federal government's decision to enforce deportations has sparked concerns among other stateless communities, notably the Bengali and Rohingya populations, most of whom reside in Karachi.

Although official figures are lacking, community leaders and confidential government sources estimate that between 800,000 and 1 million Bengalis and Rohingyas currently live in the city, primarily in its coastal regions. Many arrived during Pakistan's civil war in 1971, and migration continued steadily until 1988.

"The recent announcement of deporting illegal refugees has given the police another excuse to harass us, as we lack Pakistani national identity cards despite living in the country for over 40 years," said Nazaul Hasan, a Bengali fisherman in Karachi’s Ibrahim Haidri coastal neighbourhood.

"With Afghans, we will also bear the brunt of the crackdown," he told Geo.tv.

Zia Ur Rehman is a journalist and researcher based in Karachi. He writes for The New York Times and Nikkei Asia, among other publications, and also assesses political and conflict development in Pakistan for various policy institutes. He tweets @zalmayzia

Data visualisation by Afreen Mirza