Feudalism, rigging or performance: What makes PPP invincible in rural Sindh?

In Feb 8 polls, PPP secured 84 seats, marking its most substantial victory in Sindh in terms of provincial assembly seats since 2008

Corruption, bad governance, dynastic politics, and feudalism — no allegation has been spared against the Pakistan Peoples Party during its 15-year rule in Sindh. However, despite the continuous barrage of accusations, the electoral landscape in Sindh has consistently tilted in favour of the PPP, defying popular expectations.

The PPP has not only emerged victorious but has done so with an increasing number of seats and votes in every general election since 2008. In the aftermath of Benazir Bhutto's assassination, in the 2008 polls, the PPP secured 69 seats, garnering 42.26% of the total votes.

Although the vote share declined slightly in 2013 to 32.63%, they managed to secure 73 seats and remained the largest party by a significant margin, comfortably forming the government.

The 2018 elections witnessed the PPP clinching 77 seats with a vote share of 38.44%. In the most recent elections on February 8, 2024, the Bilawal-led party secured 84 general seats, marking its most substantial victory in terms of seats since 2008.

The question that arises is: What factors have propelled this consistent victory for the PPP? Critics insist that PPP capitalises on the lack of education, the feudal system, and alleged election rigging to maintain its dominance in the second-largest populace province of the country. But do these theories withstand scrutiny based on facts and logic?

Abysmal opposition

The PPP faces two major opponents in rural Sindh — the Grand Democratic Alliance (GDA) and the Jamiat Ulma-e-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F). The GDA, a coalition of anti-PPP parties, includes the Pakistan Muslim League-Functional (PML-F), Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), PPP-Shaheed Bhutto, and nationalist parties such as Qoumi Awami Tehreek (QAT), Sindh United Party (SUP), and Sindh Taraqi Pasand Party (STP).

The dominant factions within this coalition, notably the PML-F and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), have had leaders who aligned with dictators on various occasions. From the inception of Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI) in 1988 to the era of Musharraf, figures like Pir Pagara, Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, Liaquat Jatoi, Arbab Ghulam Raheem, and others have positioned themselves among those not only supporting but also benefiting from these illicit forces.

In contrast, the narrative for nationalist parties such as the QAT, STP, and SUP takes a different trajectory. While one might argue that after the enactment of the 18th amendment, these parties lost their focus on exposing the exploitation of Sindh's resources, senior journalist and former general-secretary of Rasool Bux Palijo's Awami Tehreek's Student wing Sindhi Shagird Tehreek, Fayaz Naich, contends that these parties still have substantial grounds for their political stances.

Issues like water, the National Finance Commission (NFC), local government issues, and governance challenges provide a foundation for nationalists to construct their arguments. However, their alignment with the GDA parties has dampened their narrative, as these parties, whose core components were once anti-establishment and anti-religious extremism, are not seen aligning with the populace that historically thrived under military rules.

On the other hand, the JUI-F has made limited inroads in locations like Larkana and Jacobabad, but being a religious party, it has not garnered the response typically enjoyed by religious parties in other parts of the country. The sufi-secular culture of the province, coupled with the absence of religious fault lines, poses challenges for them in building a compelling narrative.

Senior journalist Mazhar Abbas observes that the JUI-F has attempted to shift its narrative towards nationalistic issues, with figures like Rashid Mehmood Soomro leading multiple campaigns based on nationalistic issues such as water. However, there remains much work to be done if they intend to mount a serious challenge to the PPP in elections.

Additionally, ethnic polarisation in Sindh has solidified rural voters' allegiance to the PPP. Despite the emergence of small factions, groups, or unions in Sindh, mainstream parties such as the PTI, PML-N, JI, or JUI-F have not effectively contested the PPP's dominance in rural Sindh.

Extensive experience in electioneering, resistance

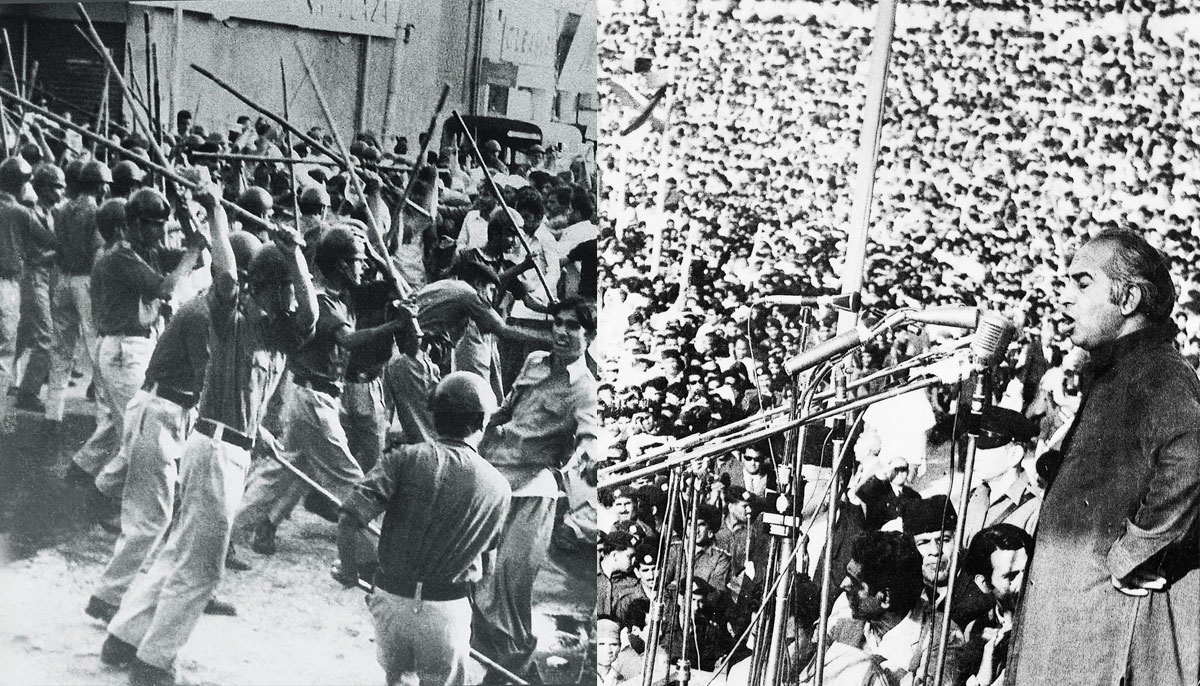

Extensive electoral experience is a key factor in the PPP's electoral supremacy, attributable to their well-established party structure and a robust electoral history encompassing 50 years of electoral and street struggles. This extended history provides them with a distinctive competitive advantage.

Since its formation in 1967, following the split of its founder Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto from General Ayub Khan's regime, the PPP has navigated through challenging periods, including the 11-year tenure of Zia-ul-Haq and the establishment of the Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD).

From facing Musharraf's era trials to the recent establishment of the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), the PPP has accumulated a wealth of experience in resistance, coalition-building, seeking consensus with adversaries, and participating in elections under the most formidable circumstances.

Sohail Sangi, a senior journalist, underscores that the electoral process is not confined to a brief three-month period; rather, it constitutes an ongoing five-year journey. In this enduring process, the PPP distinguishes itself as the solitary and unwavering participant in Sindh.

Post-polling, the PPP seamlessly shifts gears, swiftly transitioning to the preparation phase for upcoming elections, maintaining an enduring focus on election-centric strategies — an approach that sets them apart from their counterparts.

Conversely, other parties, including the GDA and JUI-F, despite enjoying regional followings, fall short of venturing into new territories to expand their voter base.

Furthermore, these parties lack a structured review process for polling outcomes, failing to systematically assess campaign errors.

Rigging allegations: Fact or fiction?

Mazhar Abbas also asserts that rigging allegations may be far-fetched, suggesting that parties other than the PPP lack the logistical capacity and understanding of the election day's intricacies.

The success of a party in polls, apart from its narrative, history, and performance, hinges on how effectively it manages the election day. Mobilising voters and bringing them to polling stations is crucial, a task at which the PPP, with its extensive electoral experience, excels compared to other parties, he adds.

As far as allegations of large-scale rigging are concerned, here is a detailed analysis of rigging allegations in specific constituencies of Sindh following the February 8 polls. These are constituencies where prominent leaders of the GDA and JUI-F contested elections from.

Firstly, rigging allegations often gain traction when victory margins are tight or the number of rejected votes surpasses the margin of victory. In this case, the margins are substantial, undermining the rigging claims by GDA leaders.

NA 203 Khairpur: PPP's Pir Syed Fazal Ali Shah defeated Pir Pagara's brother Pir Syed Sadaruddin Shah Rashidi by over 30,000 votes.

NA 206 Naushero Feroz: PPP's Zulfiqar Ali Behan secured victory over GDA's Ghulam Murtaza Khan Jatoi by over 54,000 votes.

NA 208 Nawabshah: PPP's Syed Ghulam Mustafa Shah triumphed over SUP's Syed Zain Ul Abdin by over 66,000 votes.

NA 209 Sanghar 1: PPP's Shazia Murree defeated GDA's Muhammad Khan Junejo by over 16,000 votes.

NA 210 Sanghar 2: PPP's Salahuddin Junejo outperformed GDA's Sairo Bano by over 42,000 votes.

NA 215 Tharparkar: PPP's Mahesh Kumar Malani secured victory over former CM Sindh Arbab Ghulam Raheem by over 19,000 votes.

NA 223 Badin: PPP's Rasool Bux Chandio defeated Zulfiqar Mirza and Fehmida Mirza's son Hassam Mirza by over 36,000 votes.

NA 227 Dadu: PPP's Irfan Leghari trounced GDA's Liaquat Jatoi by 11,000 votes.

The only exception was NA 191 of Jacobabad, where PPP's Ali Jan Mazari beat JUI-F's Shahzane Khan with a margin of 3,300 votes.

Moreover, candidates like Saddaruddin Shah, Jalal Mehmood Shah and Ayaz Latif Palijo have been losing to the PPP for the last two to three elections.

Moreover, Fayaz adds that the only time the SUP had won the Sakrand seat (NA-208 Nawabshah 2) was in 1988 when the PPP did not field a candidate against them.

Ayaz Latif Palijo’s father and founder of Awami Tehreek Rasool Bux Palijo lost to the PPP twice from the National Assembly seat of Thatta, and former Pir Pagara Pir Shah Mardan Shah lost to the PPP in his home constituency in the 1988 polls, he added.

The huge margins, the instant results announcement, and the electoral history of the province indicate that there might have been some irregularities in the polling process but there is no proof of large-scale rigging in favour of the PPP.

Mix of performance and power politics

Performance-wise, Mazhar Abbas argues that the PPP has not lived up to expectations in its 15-year reign in Sindh. Despite flagship health-related projects like the NICVD, SIUT, and the Gambat Liver Centre, the overall performance seems insufficient when viewed in the context of the continuous rule, he adds.

“However, the PPP manages to secure government jobs, tenders and other benefits for its supporters. Another key factor is that the PPP has been able to attract electables from the GDA or other parties, leading to sweeping victories in the last two elections."

Electables such as the Junejos of Sanghar and the Jamote family of Matiari always gave a tough fight to the PPP in all previous polls but they have joined the PPP in the past five to seven years.

The feudal influence?

The prevailing perception of the PPP suggests that it leverages the existing feudal structure in rural Sindh, utilising it as a means to ascend to power and subsequently employing it to sustain that power.

While there is some truth to the fact that numerous feudal figures (waderas) align with the PPP and have consistently been elected in the last four elections, the phenomenon of feudalism is not exclusive to the PPP.

Contesting candidates against the PPP also hail from the same socio-economic class. Individuals such as Pir Pagara's brother Pir Saddaruddin Shah, Zulfiqar Mirza of Badin, Liaquat Jatoi of Dadu, Ghous Ali Shah of Khairpur, and Arbab Ghulam Raheem of Mirpurkhas belong to the same Wadera class.

Mazhar Abbas contends that this phenomenon extends beyond Sindh. Sardari (tribal chiefdom) system, he argues, is deeply rooted in Balochistan’s culture, Punjab has its biradaris (caste-based kinship networks), and in KP there is the tribal system, which significantly influences electoral dynamics.

This is not merely a provincial disparity but rather a rural versus urban divide. In urban areas, political party narratives and ideologies play a pivotal role in shaping electoral trends, whereas in rural areas, the biradari, sardari, and wadera cultures take precedence.

Additionally, the PPP has also made significant inroads in urban centres of the province in the last two general polls. In Karachi, the PPP won 8 National Assembly seats in the Feb 8 polls and won one (NA-221) out of three NA seats in Hyderabad.

PPP's enduring electoral success in Sindh is a complex interplay of factors, including ineffective opposition, the lack of electoral experience by rivals, effective political strategies, and the party's ability to mobilise voters.

While criticisms of their governance performance persist, the PPP's political manoeuvres and strategic alliances have proven instrumental in maintaining their stronghold in the province. Understanding the nuanced political landscape in rural Sindh is crucial for comprehending the PPP's sustained dominance over the years.