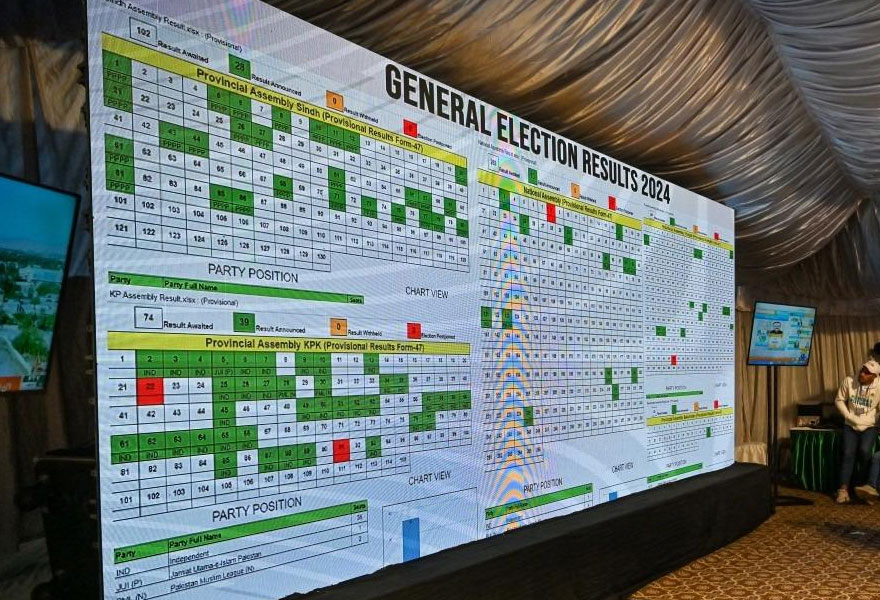

A Rs280 million experiment: Did the Election Management System (EMS) fail on poll day?

The final results of the over 800 constituencies were completed by the Election Commission of Pakistan by the evening of February 10, after a delay of nearly 40 hours

Six hours after polling had closed on February 8, boxes were still piling up in the office of a returning officer (RO), in charge of a hotly-contested national assembly constituency in central Punjab

Inside the boxes were ballot papers and original forms documenting the count of each polling station in the constituency.

Yet, by midnight, the data entry operators, inside the RO’s office, made little effort to log the tally into the specially-designed Election Management System (EMS).

Outside, presiding officers (POs) wandered aimlessly, unsure when the results from their polling stations would be fed into the system, bringing an end to their long day.

The screen, displayed outside the office, which was to provide results in real-time to the media, was also blank.

“An estimated 70% of the results had arrived by 12 am,” said a reliable source, who was an eyewitness to the developments, “But strangely, none of the data [entry] operators were typing the results into the system. Presiding operators were being told to just wait.”

Then, around 1 am, “an important looking official” showed up, said the source. He had everyone, including the election observers, removed from the RO’s office.

“I don’t know what happened inside after that,” the source said.

What is the Election Management System?

Months before the country went into general election, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), Pakistan’s election oversight body, had boasted of developing a new “state of the art technology”, known as the Election Management System (EMS).

It promised the System would ensure “fast, secure and speedy” tabulation and compilation of election results on February 8.

In fact, in the run up to the polls, a video was shared by the ECP, in which a narrator bragged that the ECP had ditched the controversial Result Transmission System (RTS), used in the 2018 polls, this time for the Election Management System.

The EMS, he added, was an “advance form” of the RTS, as it could continue to collect results even when offline, promising its reliability even in case there is internet connectivity failure.

“There is no way that results will not reach the ECP [on election day],” he assured, “The ECP has full faith in the EMS.”

But come election day, the polling results trickled in at a snail’s pace, missing the legally allotted deadline by a large margin.

As per the country’s election laws, complete results are to be announced at 2am the following day or maximum by 10am, along with a written explanation from the election staff on why the count was delayed.

Yet, the final results of the over 800 constituencies, national and provincial, were completed by the Election Commission of Pakistan by the evening of February 10, after a delay of nearly 40 hours.

Not only was the tally late, the ECP’s explanation was late too.

It took the Election Commission three days after the parliamentary polls – on February 12 – to put together a response to countrywide allegations of rigging and unusually delayed results.

The commission released a two-page statement claiming that “it became impossible for presiding officers and returning officers” to send data electronically on the day of the election as cellular signals were switched off owing to security concerns.

Moreover, it alleged that the distance between polling stations, some polling stations being located at “far flung areas”, snow in some constituencies and protests in others, had further compounded its ability to transmit results on time.

It is also pertinent to mention that the government had suddenly suspended mobile phone services nationwide on the morning of election, February 8, and restored them on the evening of February 9.

Still, none of the above reasons explain why results of two constituencies in central Punjab were held back till midnight and not even entered into the EMS, as confirmed by eyewitnesses.

The Election Commission of Pakistan did not respond to Geo.tv’s request for comments at the time of the writing of this report.

Separately, a government official, who asked not to be named, told Geo.tv that the Election Commission spent around Rs280 million of public funds to have the EMS developed by a Karachi-based information technology firm, Sapphire Consulting Services.

Geo.tv wrote to Sapphire Consulting, as well as called them on their Karachi number for comments. No response was forthcoming on email, while over the phone, the company also refused to answer Geo.tv’s repeated calls.

As of now, there is little evidence to suggest that the EMS was even fully utilized on the day of polling.

Another source, who was present at an RO’s office in Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital city, told a similar story of lack of transparency and tardiness as soon as the results began to pour in.

Soon after polling closed, according to the official, cars were lining up to drop presiding officers carrying official results. Yet, these results barely made it to the screen fixed outside the RO’s office, meant for the media and election agents.

The source also told Geo.tv that even election observers, carrying official cards issued by the ECP, were not allowed inside the rooms where the EMS was being operated.

“The room was locked from inside,” the source said, “They [the observers] stayed till midnight awaiting access, and then left. The monitoring of system [EMS] was inaccessible, even to independent observers.”

In its report published after the polls, the Islamabad-based Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) wrote that returning officers did not allow its observers to oversee the tabulation process in 135 national assembly constituencies, out of the 260 it sent its teams to.

That, it added, was a violation of the election law which allows accredited observers to observe the consolidation of results.

While in its report about the general election 2024, the Lahore-based Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) gave a score of 49% to the quality of the February 8 polls, which, it added, was lower than the overall score of the past two elections in Pakistan.

What do the ROs have to say?

In order to understand why the EMS, a system that cost Pakistan’s taxpayers millions of rupees, was ignored on election day, Geo.tv reached out to nine returning officers in Punjab.

All nine either cut the call, after hearing the questions, or refused to speak to Geo.tv about the EMS. One even pleaded that the “matter was too sensitive” to discuss.

Geo.tv then also reached out to six ROs in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and received a similar nonresponse.

— Header and thumbnail image created using AI