Labour lows: A mayday for trade unions in Pakistan

If allowed to operate freely and efficiently, trade unions can be transformative in helping create a fairer and more equal society

Trade unions have always played a crucial role in defining workplace safety, ensuring fair treatment, and protecting workers' rights. Strong unions protect members against employment instability, hazardous conditions, and exploitation, serving as a collective shield. However, with growing challenges compromising the trade unions' capacity to operate efficiently and represent workers' interests, Pakistan's current situation regarding trade unions is rather alarming.

Pakistan's once-vibrant labour union movement has been methodically undermined over the last decades. Workers cannot organise under the legal cover of trade unions because the third-party contract system has been introduced and legalised in industries and companies.

Many workers now work on temporary contracts, often without basic facilities or employment stability; therefore, depriving them of their right to organise or negotiate collectively is the current state of affairs in Pakistan. Workers know they may be fired and have no desire or capacity to organise for their rights, so this contractual structure has produced a divided and fragile workforce.

Although Pakistan has ratified 38 International Labour Organisation (ILO) Conventions, including those that provide the right to organise trade unions and participate in collective bargaining, these rights remain largely unattained. Legal frameworks, notably the Industrial Relations Acts, impose strict criteria for union registration. Even when these requirements are satisfied, the procedure is intensive, and companies may oppose unionisation initiatives because they see them as a threat to their commercial interests. Under the law, the provincial labour department is required to inform companies that it has received an application for trade union registration, said Nasir Mansoor, general secretary of the National Trade Unions Federation.

"In response, the company management denies that the trade union leaders are their employees, effectively thwarting the attempt to implement the law," said Mansoor, that companies have created “pocket unions” to comply with the demands of their foreign buyers, producing goods in Pakistan before exporting them. Moreover, under the European Union's Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) Plus, Pakistani companies are obliged to implement at least 10 core labour standards of the ILO, one of which is the formation of trade unions, and another is the collective bargaining agents (CBA).

A similar situation exists with the labour courts.

“When a worker or trade union takes a case to a labour court over a company’s violation of labour laws, the company denies that the worker was ever its employee," said the senior trade union leader.

Third-party contractors are so common that they have diminished workers' negotiating strength. In industries like textiles and clothing, which employ 40% of industrial labour, most employees have no official job record, pay stub, or written contract. Along with encouraging wage theft and benefit rejection, it is very hard for employees to pursue legal action or show their ties 4 with a specific company. Companies often disclaim any employment connection when labour rules are broken and workers seek labour tribunals, depriving workers of protection or compensation.

Furthermore, the ineffective enforcement of labour rules is exacerbated by the influence of wealthy businessmen, many of whom wield significant political power. This lack of responsibility helps maintain a society where labour rights abuses are commonly disregarded, remarks Nasir Mansoor.

Collective bargaining, a pillar of labour union activity, has almost disappeared from Pakistan. Legislative barriers, including the broad powers granted to the Registrar of Trade Unions and the classification of many sectors as "essential services," further restrict workers' rights to organise, strike, or negotiate for better conditions.

"It is the responsibility of labour inspectors to ensure the presence of trade unions in a factory or company unit under the Factories Act 1934, but the labour department is not fulfilling its responsibilities," said Mirza Maqsood, another trade union leader, now associated with the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER).

According to him, if the government is to reverse this trend, it must enforce labour laws, change restrictive regulations, and guarantee that every worker, regardless of their employment status, may freely use their right to organise and bargain collectively.

Historic injustices to workers

Pakistan's Constitution allows every worker to form or join a trade union, where they can exercise the right to collective bargaining.

Colonial legacies, military governments, strict regulations, and economic shifts have contributed to Pakistan's complex history of trade unions, which has often been repressed. With less than 2% of Pakistan's workforce unionised today, trade unions remain a diminished but essential voice for the nation's working class.

Pakistan acquired its labour laws from British India at the time of independence in 1947, notably the India Trade Unions Act of 1926, which gave trade unions legal recognition and protection. A British Indian legislation body also passed another major labour-related law, the Trade Disputes Act of 1947. Pakistan inherited both these key laws until the formation of its first Constitution in 1956, which martial law abrogated.

The first significant blow to unionisation was the imposition of martial law by the military dictator General Ayub Khan in 1958. This coup resulted in the deletion of essential labour regulations and the banning of trade unions. Under Ayub's military government, stringent laws were enacted, including the Industrial Disputes Ordinance of 1959, which expanded the concept of "public utility services" to encompass commercial industries such as textiles and sugar. In most sectors, this made strikes almost impossible.

In practical terms, from 1958 to 1969, the country had no trade union law. When the powers were transferred to another military dictator, General Yahya Khan, in 1969, his military regime enacted the Industrial Relations Ordinance 1969, which dealt with both trade union registration and industrial disputes.

Still, throughout democratic times, trade unions saw notable expansion despite suppression. Under prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the most obvious development occurred in the 1970s. Considered among Pakistan's strongest pro-worker policies in the past years, his administration unveiled the 1972 Labour Policy. Welfare organisations, such as the Workers Welfare Fund and the Employees' Old-Age Benefits Institution (EOBI), also emerged from this.

With around 8,000 recognised unions, union membership peaked in 1977 at about a million.

But General Zia-ul-Haq's regime overturned these advances. The military dictator forbade labour inspections, pushed contract employment, and opposed union activities. The unionised workforce dropped significantly as neo-liberal economic policies and a tsunami of privatisation, particularly in the 1990s and 2000s was unleashed. Long regarded as union strongholds, state-owned companies were sold, and widespread layoffs resulted from declining worker rights.

Neo-liberal economy and labour's predicament

Trade unions and official sector workers experienced significant changes as neo-liberalisation policies were adopted in Pakistan, particularly from the late 1980s onward.

Emphasising deregulation, privatisation, and a smaller state involvement in economic matters, these policies were pushed under the Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)

Traditionally, unions relied on permanent employment arrangements to organise and negotiate, and the shrinkage of the formal sector and the increase in contract and third-party employment significantly damaged them. Moreover, limitations on labour inspections and collective bargaining degraded union authority, reducing union membership and negotiating strength in the official sector.

The emergence of informal employment, now accounting for more than 70% of non-agricultural employment, has further lessened the significance of conventional trade unions. Particularly for women, home-based labour, casual labour, and outside contracts predominate on the job scene.

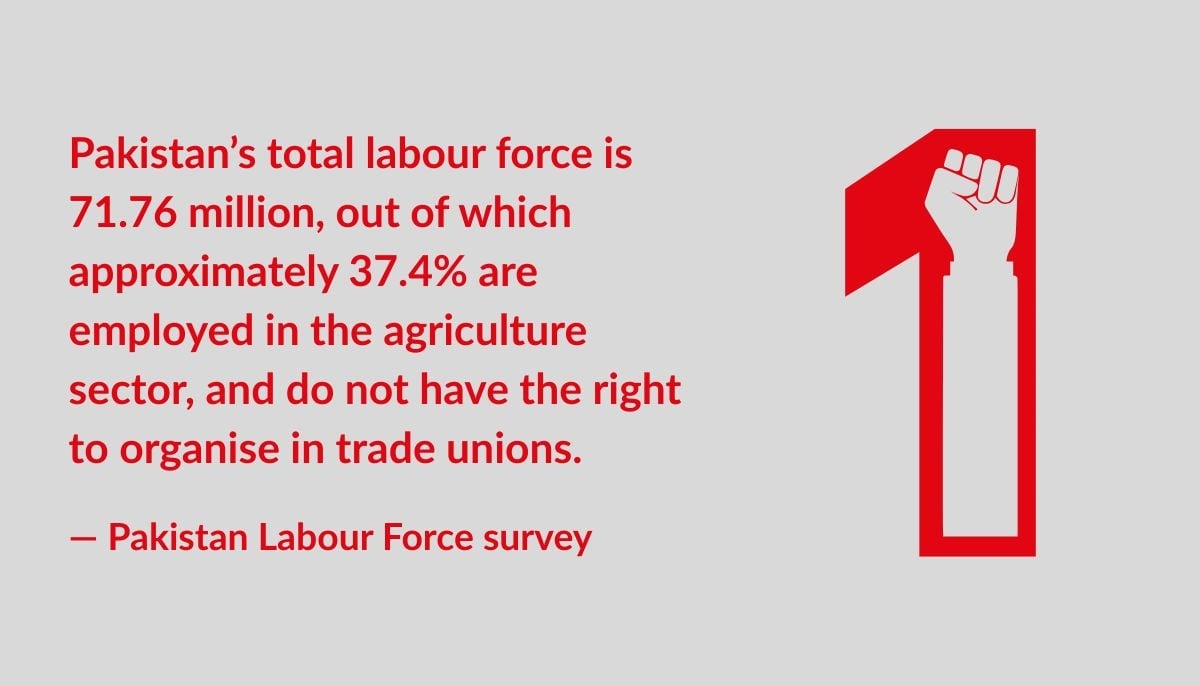

According to the Pakistan Labour Force Survey 2020-21, the total labour force in the country is 71.76 million, out of which approximately 37.4% are employed in the agriculture sector, and do not have the right to organise in trade unions. In contrast, the share of employment in the services sector is 37.2%, and in industry, it is 25.4%, where trade unions can be formed. The employment share in the overall formal industry decreased from 27.6% in 2018 to 27.5% in 2021, while the share of the informal sector increased to 72.5%.

With over half of Pakistan's population made up of women, labour unions still shockingly under-represent them. Most labour in the agricultural and at-home sectors is excluded from official labour rules. While initiatives like the Sindh Women Agricultural Workers Act, 2019, and the Sindh Home-Based Workers Act, 2018, aim to include women in the workforce, their implementation remains inadequate.

Trade unions post-18th amendment

Notwithstanding these obstacles, some positive changes are happening. Labour became a provincial subject with the 18th Constitution Amendment in 2010. Since then, the Sindh government has conducted tripartite labour conferences, declared a provincial labour policy in 2018, and established a minimum wage board to fix pay for unskilled workers.

Moreover, all the major federal labour laws have been made at the provincial level. Prominent are the Industrial Relations Act and the Factories Act; however, enforcing labour laws remains a significant challenge. Other provinces have also made their labour laws. Workers still often earn significantly less than the legal minimum wage; many women are paid substantially less.

Just a tiny fraction of Pakistan's 71.76 million-strong workforce is unionised today, and most unions are limited to the formal sector and bigger companies. According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), as of 2016, only 1,390 of the roughly 7,096 registered unions held collective bargaining agent status. Union power to influence industrial relations has been significantly diminished, as referendums to choose negotiating representatives are infrequent and sometimes manipulated.

The lack of accurate, centralised statistics on the workforce, especially those in informal employment, is a key obstacle impeding development. Extending social safeguards or implementing significant changes becomes challenging in this regard. This difficulty is evident in the government's admission that it possessed statistics for only 20% of daily-wage workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Future of trade unions

Trade unions are vital for defending workplace safety, fair treatment, and workers' rights—they are not just about pay negotiations. Strong unions help protect individual workers from job instability, hazardous working conditions, and exploitation.

Many changes are sorely required if Pakistan's labour union movement is to be rebuilt. First, there must be universal social security that covers all workers, regardless of their job situation. The Constitution should include social security as a basic entitlement. Second, the frequent recalculation of the minimum pay should reflect the cost of living and inflation, so systems for rigorous execution must be established. Third, returning to a modernised form of the Trade Union Act 1926 helps restore the freedom to unionise and collectively negotiate completely. Fourth, sectoral and industrial unions should be supported above enterprise-level unions to accommodate casual and home-based workers.

Finally, openness and labour data collection must take centre stage. To guarantee that all formal or informal employees are counted, protected, and supported in times of need, they should be recorded in a centralised digital database.

The welfare of Pakistan's people significantly determines its economic destiny. If allowed to operate freely and efficiently, trade unions can be transformative in helping create a fairer and more equal society. However, the state must go beyond mere laws and aggressively empower the nation's most underprivileged workers if this is to occur.

Shujauddin Qureshi is a senior journalist and communications specialist with extensive experience working for human rights and labour rights organisations, including the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER). He can be reached at [email protected]

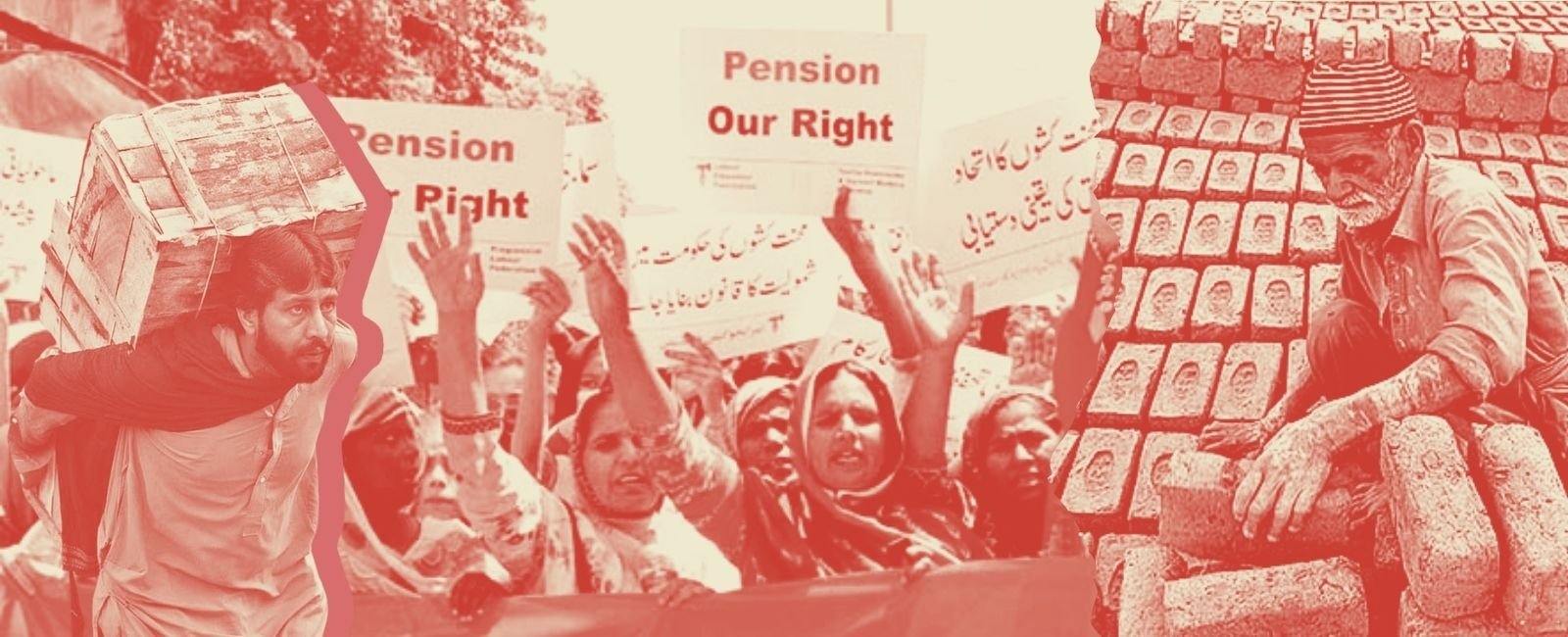

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv