Bringing back Lahore's lost soul, brick by brick, moment by moment

Punjab govt has launched a broader restoration plan to revive Lahore's heritage sites and bring city's glory back

Lahore’s story likely began nearly 2,000 years ago, but it isn’t mere age that defines this city, it’s the way culture, flavour, and history have clung to its old walls and new streets ever since.

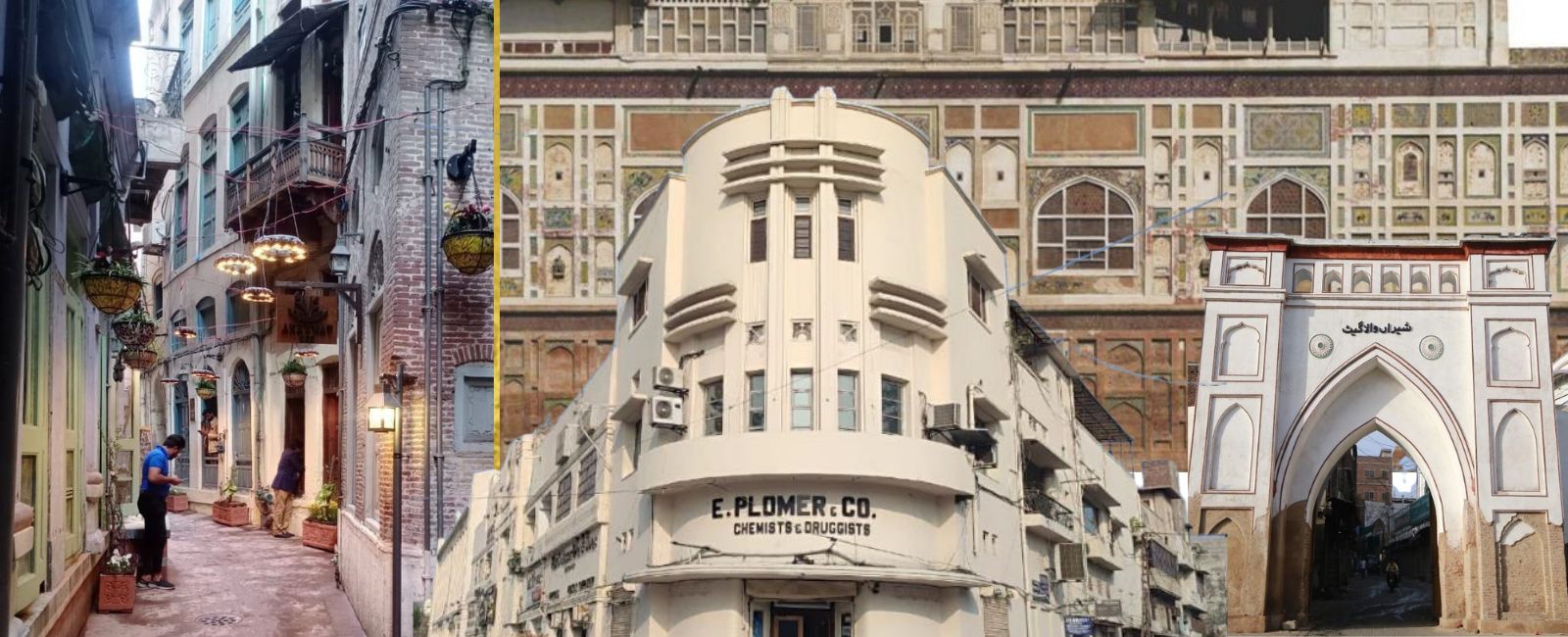

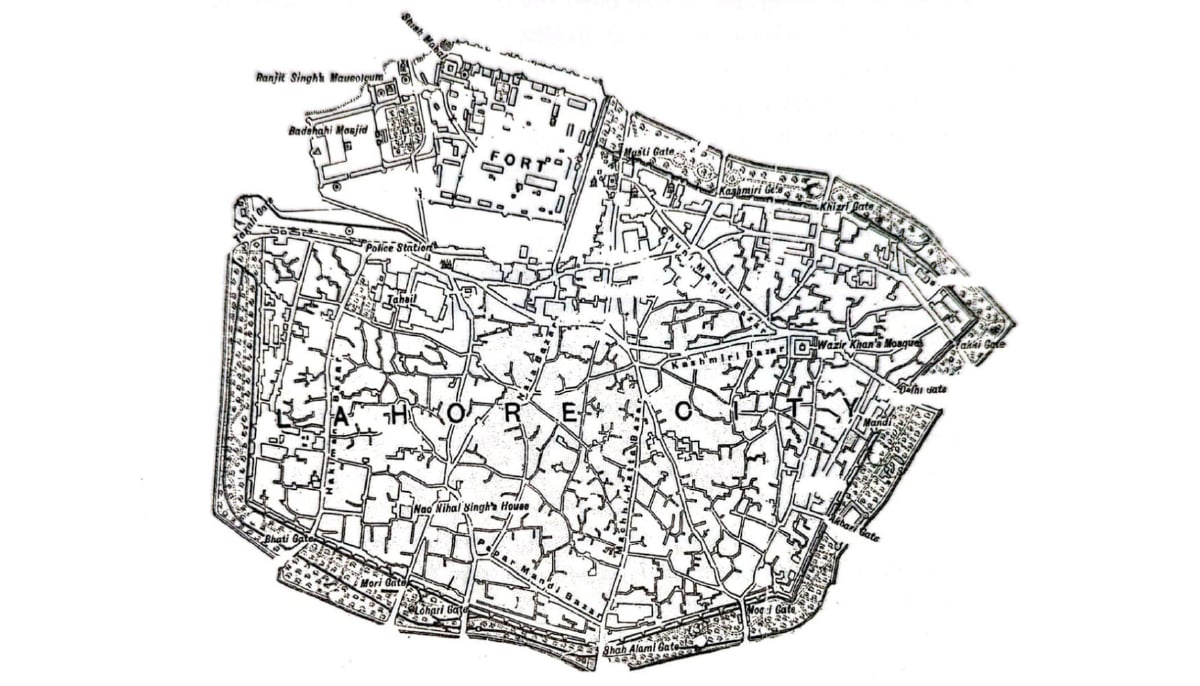

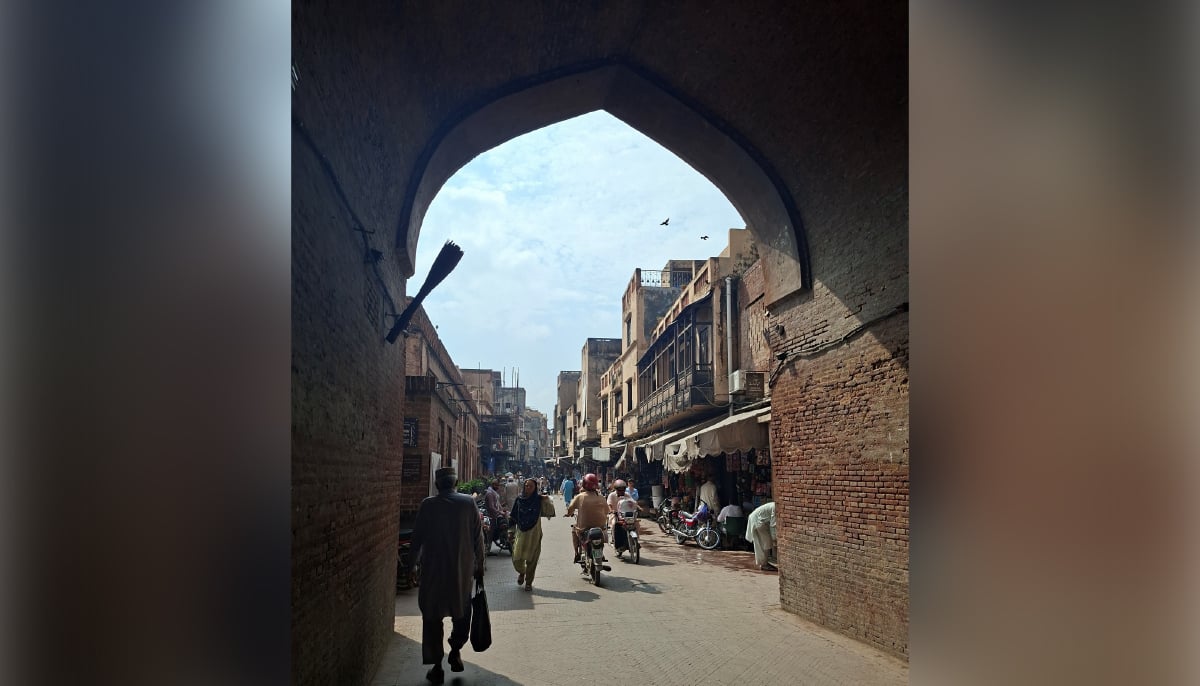

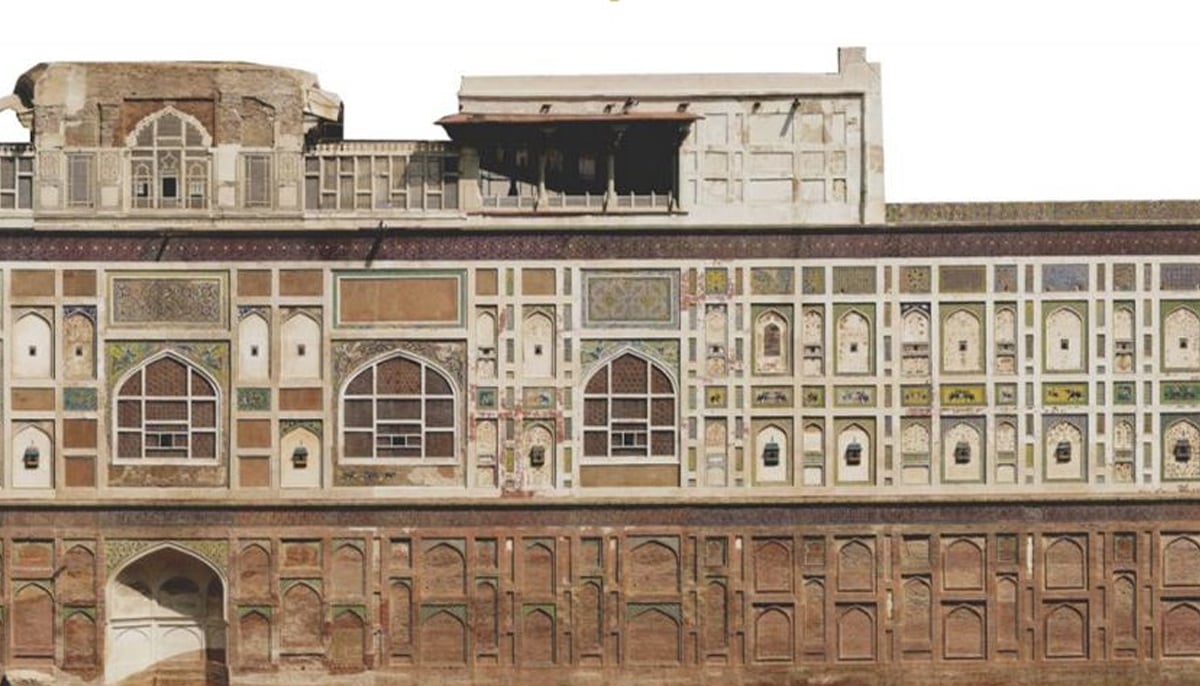

Ruled by Ghaznavids, Mughals, Muslim dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate, Sikhs, British and destroyed by the Mongols. Lahore’s earliest rulers, however, trace back to Hindu and Buddhist civilisations. In the old city of Lahore, the landscape reflects the architecture of those eras. The city boasts the remnants of Mughal grandeur, the Hindu houses and temples, Sikh gurdwaras and many colonial buildings. The walled city or old Lahore has only six of its 13 gates intact. Over the years, particularly after independence, many new buildings were constructed as old ones were demolished, many without an approved plan in the middle of historical Lahore.

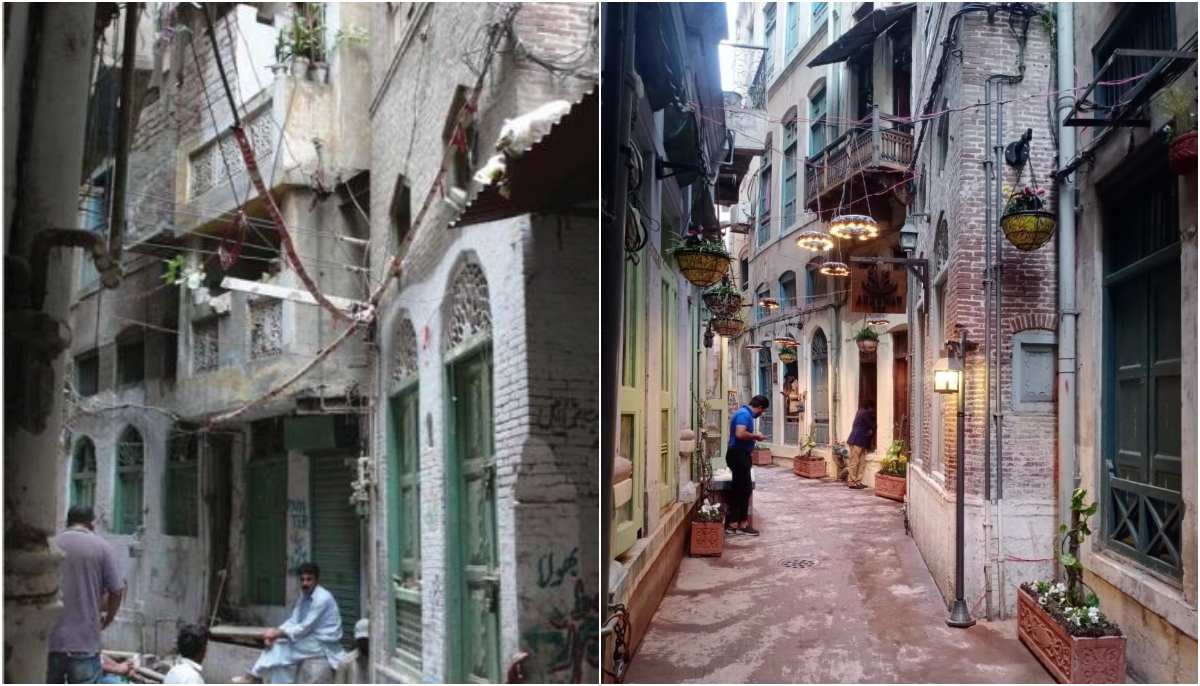

As old residents moved to newer parts of the city, many demolished their ancestral havelis. In their place rose soulless concrete blocks, bearing no trace of old Lahore’s grace. Now, the city’s heritage stands buried, its beauty suffocating like a flower trying to bloom in a swamp.

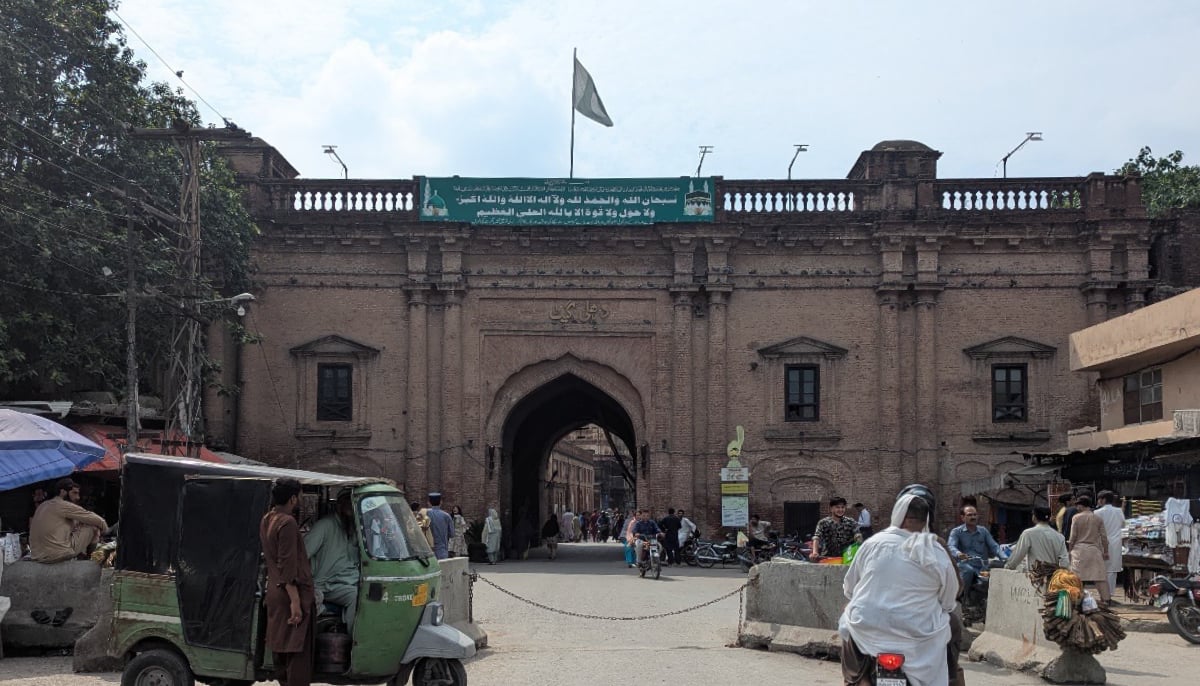

In 2006, a rehabilitation initiative for the Walled City began with support from the World Bank. By 2012, the Walled City of Lahore Authority (WCLA) was formally established. The first pilot project focused on restoring the 1.6 km Shahi Guzargah, the Royal Trail, linking Delhi Gate to Lahore Fort. Supported by the Aga Khan Cultural Service - Pakistan, the six-year effort included sealing open sewers, laying underground wiring, clearing encroachments, and restoring over 850 façades. The area was transformed into a walkable heritage path.

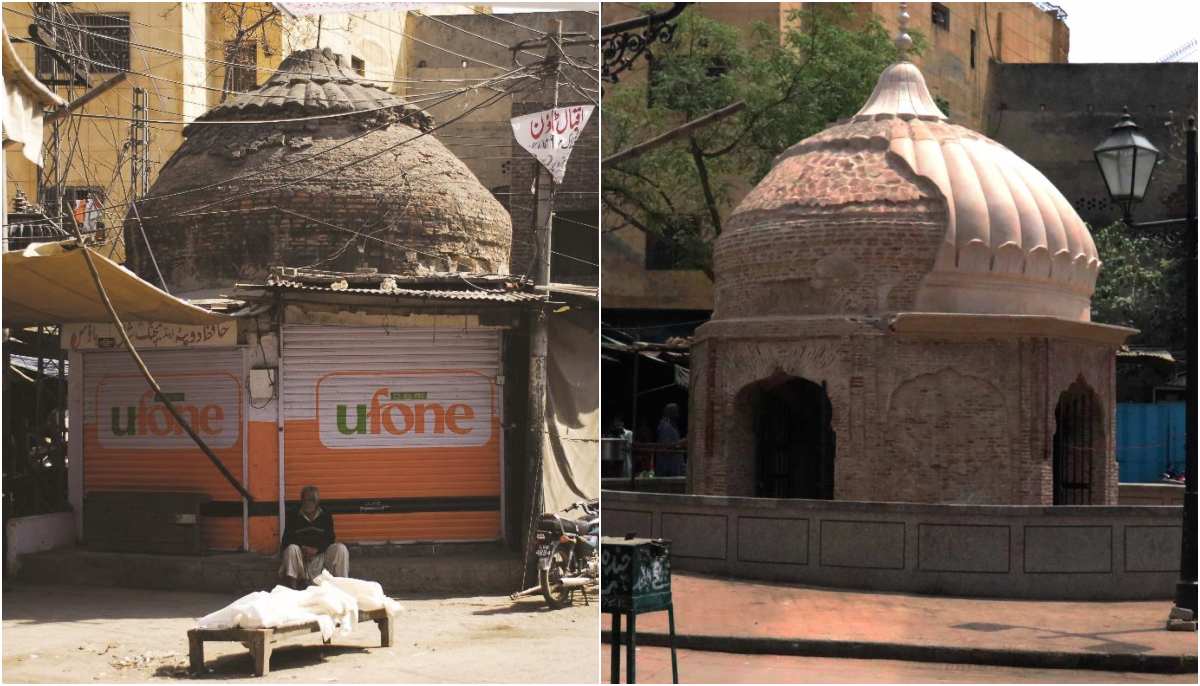

Now, Punjab’s government has launched a broader restoration plan. Phase one includes rebuilding the Walled City’s missing gates and connecting walls, adding a circular garden, and preserving landmarks like Neela Gumbad, Shalimar Garden, Shahdrah monuments, and the Old Steam Pump House. The project also includes work on Lahore Fort, Mall Road, historic zones, and key academic areas like Punjab University and Government College. Over 2,700 properties are slated for restoration or façade improvement.

To support this transformation, the government plans underground parking along Mall Road and underground shops at Neela Gumbad to relocate traders affected by reconstruction. The project, expected to cost Rs64 billion, has received an initial Rs30 billion. WCLA aims for completion by end-2027, promising a revitalized Lahore to boost heritage tourism.

We visited the restored Shahi Guzargah near Delhi Gate and spoke to traders in Neela Gumbad’s Cycle Market, Gur Market, Rim Market, and shopkeepers outside Delhi Gate to understand how this restoration impacts locals.

A trail restored, but still hard to walk

The Shahi Guzargah, where not only Shahi Hamam and Masjid Wazir Khan were restored, but several old havelis were also revived.

Some newer constructions were also given a facelift to match the vibe. One cannot help but appreciate the effort; the mere fact that someone tried to restore some of the city’s past glory is commendable. While the visual revival is admirable, navigating the trail is another story. The streets are clogged with motorbikes and carts, and despite improved infrastructure, waste and foul smells persist. The vision of a tourist-friendly walkway still feels distant.

Gali Surjan Singh, once photographed as a peaceful floral street, now buzzes with traffic and chaos. While residents may be used to these conditions, they pose a challenge for visitors. Motorbikes dominate, and with limited public transport and ingrained habits like littering, creating a clean, walkable space is proving tough.

Urban planning consultant Izhar-ul-Haq notes, “The physical restoration of Shahi Guzargah was a significant step, havelis, facades, sewage, all improved. But making it walkable has been difficult. These are living neighborhoods. Without better traffic control and community engagement, the daily hustle overshadows the charm.”

Neela Gumbad’s cycle market: sacred space or development target?

WCLA plans to demolish 72 shops in Neela Gumbad’s Cycle Market to reveal the tomb of Hazrat Abdul Razzaq Makki and build a park. Shopkeepers argue the shops are waqf property built to support the mosque’s upkeep and have been paying rent to Department of Auqaf for generations.

Muhammad Ali, who runs one of the oldest shops, said, “Our family has been here for generations. The government talks of compensation and alternate shops, but we’ve seen nothing in writing.”

Another shopkeeper Syed Haroon said, “They promise compensation for a year’s loss, but what about our staff? Shut us down, and we lose our customers. Build our new shops first, then talk about demolition.”

He also questioned selective enforcement: “They’re targeting us for being near a shrine, but what about the FBR building next to Baba Mauj Darya’s mausoleum?”

DC Lahore Syed Musa Raza stated the land belongs to Auqaf and that shopkeepers will receive one year’s compensation and alternative shops, once they’re constructed.

Yet skepticism remains. Haroon warned that the planned park could fall into neglect, like the nearby pond now overtaken by drug users and waste.

Delhi Gate, the fortified wall, and Rim Market

Over 2,000 properties may be impacted by the new fortified wall and garden. Walyat Ullah, a shoemaker near Delhi Gate, recalled losing his shop during the 2013 restoration: “We were told plazas would be built at Delhi, Mochi, and Bhaati gates, but there’s been no confirmation.”

Many traders rent these government-owned shops at minimal rates. Asif, a spice market vendor, said, “My shop has been here for the last 60 years. Government reps used to visit and update us, now no one comes. We don’t know where we stand.”

Rim Market, opposite the back of Shahi Qila, is also slated for removal.

Its president, Muhammad Nabi Khan, President of Rim Market, said, “No one from the government has approached us so far.

“Before 1964, this market was near the railway station and was relocated here and we continued paying rent until 1996, but now no rent is being collected”.

“There were some rumours and news reports claiming that a deal had been made for 364 shops in Rim Market — that’s completely false.

“No such deal has happened. A year or two ago, the government said it would give us land in Kala Shah Kaku.

“If they intend to demolish the market, then they should at least give us space within the Walled City or close to it”.

Protests by Shah Alam traders previously forced the government to scrap shop relocations there. For now, officials are focusing on structural restoration and façade improvement instead.

Haq feels that the initiative by the Punjab government is much needed, as Lahore’s rich heritage deserves to be preserved and celebrated, but it comes with challenges.

“One of the most pressing concerns is the proposed demolition of over 2,000 properties—mostly shops.

“That is a huge number, and behind each shop is a family, a livelihood, and years of hard-earned stability.

“If these demolitions go ahead without proper compensation, relocation plans, or meaningful consultation, the social cost could be immense”.

“Are we restoring heritage for the people of Lahore, or are we turning it into a curated tourist attraction?

“If the focus shifts too much towards beautification and spectacle, we risk sidelining the very communities that give these spaces life and meaning.

“Heritage conservation should never come at the expense of those who live and work in these areas,” the urban planner said.

He feels that rebuilding the wall and creating a circular garden in such a densely built-up area will be no small feat.

“It will require careful planning, engineering expertise, and above all, coordination among multiple government bodies—something that has historically been a challenge in our urban governance”.

What Lahore can learn from Istanbul and Delhi

In cities like Delhi, Istanbul, and Marrakesh, old quarters are preserved, not altered.

Dr Nasir Javed, ex-CEO of Urban Unit, shares the same sentiment.

“If we go to Morocco, to Delhi, Colombo or Istanbul, their historical areas and old quarters are preserved, and no new buildings are there”.

Dr Javed was the first director of the Walled City project when it was started in 2006. According to him, at the time, they identified around 2000 buildings in the walled city for restoration and preservation. He shared that back in 1995-96, the number of these old buildings was 4000, but they had already been destroyed before the project started.

"There are two types of architecture and historical preservation. One is where the area is isolated and turned into a monument for tourism, like the Shahi Qila and the Badshahi Mosque. But the more common and I would say, the latest trend is the living preservation.

“When we originally started designing in 2006, walled city Lahore was basically a living city that needed to be preserved. The plan was to make it a living monument where people live in the area, and it is just not reserved for tourism, and that is challenging”.

He thinks that teaching civic science and common sense is vital in maintaining such projects, which he laments is not on any government's agenda.

“We don't just preserve the culture; we also train the citizens to maintain it. If we expect just the city authority or municipality or WCLA to keep it clean, it will never happen," he said.

Haq added that Lahore did not grow with a proper plan.

“Over time, it expanded like a jungle—shops popped up wherever there was space, houses were built without approvals, and the city kept growing without much control.

“Now, many people have built their lives around these gates and their shops and homes may not be legal on paper, but they are real, and they support families.

Simply removing them for restoration, without offering a fair solution, would be unfair and could create serious problems, he said.

“As for bringing back the aura of old Lahore, the charm, the atmosphere, it is a beautiful idea, but we have to be realistic.

“The city has changed a lot. We may not be able to fully recreate the past, but we can aim to bring back some of that feeling.

“Instead of demolishing everything, we should try to improve what is already there.

“For example, old-style facades can be added to existing buildings, streets can be cleaned and organised, and the area can be made more welcoming for both locals and tourists.”

As GC Walker wrote in the 1893 Gazetteer of Lahore: “Lahore with its numerous gardens, tombs and ornamental gateways must have been, in the days of its splendour, a fine specimen of an Indo-Mughal city; and though no city has perhaps suffered more from devastations and the hand of time, it can still show no mean specimens of architecture”.

It was true back then, and it is true now.

That Lahore had been destroyed by the attackers, and this Lahore by its own people. One can only hope this restoration projects bring some glory back to this lively city. The city will continue to grow and evolve; it is our responsibility to decide the direction it takes.

Nadia S Malik and Momna Tahir are staffers at Geo News.

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv