Heat waves in Pakistan, India could render urban areas unlivable: report

Both countries are at a heightened risk of disasters arising from natural disasters and climate events

January 17, 2020

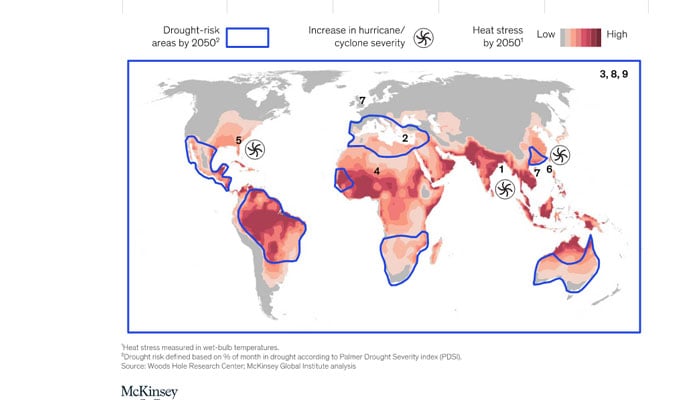

Urban areas in parts of India and Pakistan could be the first places in the world to experience heat waves that exceed the survivability threshold for a healthy human being, United States-based think tank McKinsey Global Institute said in a report released on Thursday.

According to the conclusions drawn from the year-long, cross-disciplinary research effort, lethal heat waves that hit the sub-continent in the next three decades could result in record-high temperatures that exceed the survivability threshold of human beings.

The study also claimed that small regions around the world were projected to experience a more than 60 per cent annual chance of such a heatwave by 2050, which will eventually affect the systems in place that would otherwise have mitigated a crisis.

Also read: World's oceans hottest on record in 2019

What is a lethal heatwave?

A lethal heatwave, as per the definition provided by the McKinsey Global Institute, is a three-day period with average daily maximum wet-bulb temperatures exceeding 34 degrees Celsius. Presently, these conditions prevail along the area on the Pakistan-India border every year.

However, the heat of the summer is contained by the high atmospheric aerosol concentrations in the region. These aerosols mask the risks posed by heat and provide some relief to the dwellers of these areas. However, in the winters, these same aerosols lead to high probabilities of smog.

Pakistan and India also lie in the region that is expected to become hotter and more humid by 2050. These changes, coupled with lethal heatwaves, droughts and dust storms, could impact water stress as well. Last year, extreme heat killed hundreds in the Indian state of Bihar alone.

Also read: 'Hoard out of greed but die of need': Karachiites join worldwide climate strike

How will rising temperatures affect Pakistan?

Pakistan was last year ranked fifth on the Global Climate Risk Index, according to research by European think tank Germanwatch. The country lost 9,989 lives, suffered $3.8 billion in economic losses, and witnessed more than a hundred extreme weather events between 1999 and 2008.

In the research report released on Thursday, McKinsey — highlighting that air-condition penetration remained a problem — claimed that the number of people living in areas with a non-zero chance of lethal heatwaves could rise to between 700 million and 1.2 billion by 2050.

The predictions made by McKinsey in their report correspond to the figures highlighted by Germanwatch. The conditions resulting from the rise in temperatures could worsen the physical and financial losses of the country, and also lead to an increased chance of extreme weather events.

Also read: 2019: The year climate change rattled Pakistan

For example, the US-based institute claimed that agricultural production would take a hit from the rising temperatures, as by 2050, the annual probability of a 10 per cent or more reduction in yields for wheat, corn, and rice was projected to increase from 6 per cent to 20 per cent.

This means that Pakistan and India, both of whom rely heavily on agricultural produce to feed their economies, could face food insecurity and shortages if appropriate measures are not undertaken by 2050 to address the issues related to rising temperatures.

"In many regions most exposed to impacts on labour productivity from heat, including India and Pakistan, a significant share of GDP currently derives from outdoor sectors like agriculture. If this share is reduced, less of the GDP of these countries will be at risk," the report stated.

Also read: South Asia's most pressing threat? Climate change

McKinsey also predicted that if lethal waves start hitting the subcontinent more often, assets could be destroyed or services from infrastructure assets disrupted from a variety of hazards, including flooding, forest fires, hurricanes, and heat.

Flooding, forest fires and heat are already huge problems in Pakistan. Every year, flooding in the summer months leads to loss of lives, as well as damage to agriculture and infrastructure. Forest cover, already very thin, is threatened by forest fires, especially in the north of the country.

Rising temperatures specifically threaten the outdoor sectors of the economy. According to McKinsey, Pakistan has a moderate risk of witnessing a decrease in the number of effective outdoor working hours that are not affected by extreme heat and humidity in the coming years.

Also read: Which celebrities attended Climate March Pakistan?

Is climate diplomacy the answer to Pak-India tensions?

Pakistan and India have been at loggerheads ever since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi revoked the constitutional autonomy of occupied Kashmir and imposed a military curfew in the area. Tensions between the neighbors can be decreased through climate diplomacy.

Many of the risks associated with the changing climate are applicable to both India and Pakistan. Increased coordination between the governments of the two countries would go a long way towards managing and even avoiding some of the risks posed by extreme weather.

One of the potential issues that the two countries need to tackle together is the problem of smog in winter months. At year-end, heavy smog engulfs the northern parts of Pakistan and India, with New Delhi and Lahore worst-hit by the rapid plunge in air quality.

Also read: Heatwave hits Australia with hottest day on record

The authorities on both sides of the border seem resigned to their fate every year. Corp burning, firecrackers that are blasted off on big festivals, pollution from cars and buses that are not running eco-friendly engines, as well as construction work, has lead to a public health emergency.

However, the challenge also presents an opportunity for the two countries. The smog that engulfs both sides of the Line of Control every year does not know geographical boundaries exist. Any long-term solution to the problem has to acknowledge this fact.

Pooling resources, comparing statistics, coordinating policy solutions that are implemented all over the region, are just some of the measures that could lead to the disappearance of the smog menace, and the beginning to a thaw in relations that provides the impetus for increased cooperation.