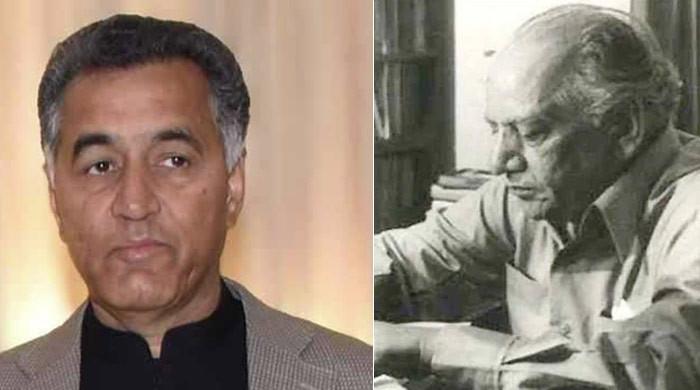

Asghar Khan is gone, but his case is still alive

'Asghar Khan was perhaps Pakistan's most honest and transparent politician, who stood for principles he never compromised on'

January 08, 2018

Former Pakistan Air Force chief Air Marshal (retd) Asghar Khan died on January 5 at the age of 96. But his case, dubbed The Asghar Khan case, is still alive.

If, and when, the case concludes, it will not only expose institutionalised corruption in Pakistan but also lay bare how state institutions assisted in rigging elections.

Khan will be remembered as someone who, despite being a former uniformed officer, went to the highest court in a bid to stop ‘political engineering’. His activism eventually led to the closure of the premier intelligence agency’s ‘political cell’.

Coincidentally, Khan died on Jan 5, on the birth anniversary of former Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Many remember the two as political rivals in 1977. But few know that in 1969, Khan joined Bhutto's hunger strike and supported his struggle against Gen Ayub Khan.

Asghar Khan was an exception in every way. He was perhaps Pakistan's most honest and transparent politician, who stood for principles he never compromised on. Disappointed with local politics, he soon dropped out of the race and spent the rest of his life at his family home in Islamabad.

Even his time as the air chief was unmatched. I still remember one of his rare press conferences at the Karachi Press Club, with two former air chiefs. He held the press talk to highlight unnecessary spending within the forces and asked for major cuts in such expenditures.

As for his political stint, it wavered between right-wing politics to liberal. If on the one hand he led the 1977 Pakistan National Alliance movement against Bhutto, on the other he supported the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy against General Zia-ul-Haq. He also challenged Haq’s decision to postpone elections in the Lahore High Court. When the court accepted his petition, the general quickly invoked the extra-constitutional Provisional Constitutional Order (PCO).

Khan led a largely clean public life. But criticism can be directed at him for two accounts:

1) In 1977, he made a notorious call asking Haq to hang Bhutto by the Kohala Bridge. It is important to note that the two men, Bhutto and Khan, had a bittersweet relationship till the very end.

2) The same year, prior to elections, he allied his party with the PNA, against the Pakistan Peoples Party.

Yet, the air chief-turned-politician refused to support Gen Haq beyond 90 days of the elections and opposed his demand of ‘first accountability then elections’.

In an interview he gave me a few years later, he said: “I was adamant that elections should be held within 90 days. But when Zia-ul-Haq decided to prolong his rule, I opposed him.”

When asked about his landmark decision to approach the Supreme Court in the Mehran Bank case, he added: “Politics should be clean from corruption. I was disturbed by the reports of the intelligence agency having a political cell. It took the court six years to answer a simple question, ‘Does such a cell exist or not?’”

In 2012, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry finally declared in a detailed order that the 1990 elections were rigged. The court then ordered the Federal Investigation Agency to investigate the fraudulent elections. To date, former army chief General Aslam Beg’s review petition is still pending in the court.

At first, Khan's petition was simple. It sought clarity on the existence of a “political cell”. But when former ISI chief Lt Gen Asad Durrani submitted an affidavit and admitted that some Rs90 million was distributed among opposition politicians, it quickly became a high profile case.

Syeda Abida Hussain is perhaps the only politician who admitted to taking the money while former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and others named in the case deny it.

When I recently met PPP spokesperson Farhatullah Babar, and asked him why Benazir Bhutto did not pursue the case, he said she was not ready to trust the establishment who had been instrumental in trying to dislodge her government in 1990.

I once questioned Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, a former interim prime minister, to determine how much truth was in the story. “It is definitely true,” he told me, “There was also an understanding that the PPP would not be allowed to win the elections and I would be installed as the prime minister.”

The case itself is proof of why democracy could not take root after 1988, and how politicians conspired against each other with the backing of the establishment.

While Khan is now gone, his case remains. It is now the responsibility of the apex court to ensure that those involved are punished and a precedent set to deter any such move in the future. That should be Asghar Khan’s legacy.

Abbas is the senior columnist and analyst of GEO, The News and Jang. He tweets @MazharAbbasGEO