Powerless to be born

There is hardly any expectation that murders in Balochistan in name of honour will bring any shift in govt's policy

July 27, 2025

What happens when a society is wounded by an incident that challenges its legal and moral values? A lot, obviously. In addition to the law taking its own course, a serious contemplation of the causes and consequences of the event is sure to be undertaken. And many things would consequently change.

Ideally, this should also happen in Pakistan. However, we tend to do things differently in this country. We have lived through some big disasters without learning our lessons. That process of social change that takes countries forward when they respond to their challenges is not for us.

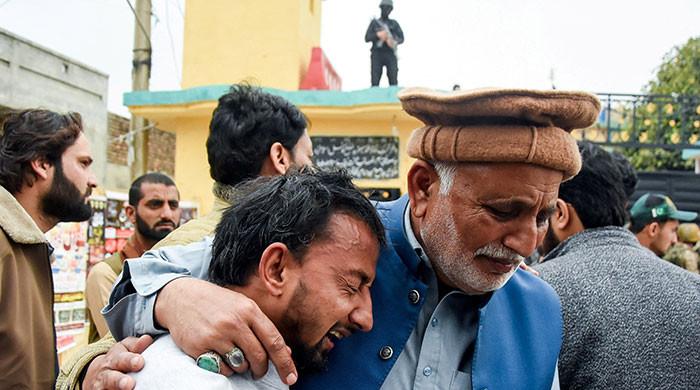

I am bothered by these thoughts because we are at this time shaken by another tragedy of the kind that raises questions about our national sense of direction. Yes, I am speaking about the 'honour killing' of a woman and a man in a desolate place in Balochistan. This entire episode, with its specific details, has left the nation in a state of shock and grief.

Actually, the murders were revealed by a video clip that became viral on social media, weeks after the heinous crime was committed. Without this, the incident involving an entire tribe would have gone unreported. I was not inclined to see the entire clip because I was already shaken by the glimpses shown on news channels and by the reports in the print media.

We may recall many somewhat similar stories of "honour killing". In this case, a tribal sardar, who is under custody, presided over a jirga and declared the two guilty of engaging in 'immoral relationship' and ordered that they be killed. The video shows a group of armed men gathered around vehicles in a deserted area. The woman, Bano, is ordered by the crowd to stand away from the vehicles and the couple is killed by a volley of bullets.

In this dreary tale, there is a compelling touch of a Greek tragedy and this relates to the courage and dignity of Bano, as I have read in reports. Let me borrow this account from The Guardian: "She tells a man in the regional Brahavi language: 'Come, walk seven steps with me, after that you can shoot me'. He follows her for [a] few steps, and she then says: 'You are allowed only to shoot me. Nothing more than that'."

It could be said on behalf of the administration that prompt action has been taken. Arrests have been made. Statements of condemnation have been issued. A resolution was passed in the Senate on Thursday, calling for swift justice in Balochistan killings.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif said in a statement: "No one is above the law and no one can be allowed to take the law into their own hands". We should not doubt the prime minister’s sincerity and resolve. But these are words that our top officials must have repeated hundreds of times. If an honour killing is an occasion to make this assertion, reports say that around 1,000 persons, mostly women, are killed in the name of ‘honour’ every year.

Al Jazeera quoted Harris Khalique, general secretary of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), as saying that killings in the name of honour confirm the ‘tyranny of medieval practices’ still entrenched in many parts of Pakistan. He added: "The state, instead of establishing the rule of law and ensure the right to life of its citizens, has protected the tribal chiefs and feudal lords who guard such practices to perpetuate their power over local people and resources".

There may be many other reasons, too, for the rulers’ inability to rid society of the many evils it is afflicted with. The result is that instead of making progress, Pakistan is trapped near the bottom of all global surveys regarding social development. We are either a dead society or powerless to be born. (This expression, I admit, is inspired by that famous quotation of Matthew Arnold: "Wandering between two worlds, one dead / The other powerless to be born".)

As I had stated at the outset, there is hardly any expectation that the two murders in Balochistan in the name of honour will bring about any revolutionary shift in the government’s policy in the context of the ongoing conflict between tradition and modernity. The blasphemy issue is one example of how vigilante justice has continued to prevail.

Finally, I want to underline a kind of paralysis and apathy that exists in our society with some evidence that I find very instructive. This is a parable I have cited more than once. And it never ceases to startle me with its astounding message.

There was this incident of fire in a Baldia textile factory in Karachi on September 11, 2012. More than 260 people were killed in this disaster. What happened? Is this tragedy engraved in your memory? How did Karachi grieve — and what changed?

Now, almost exactly one hundred years before that, there was a similar incident in New York. What is known as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire had taken place in March 1911. More than 140 garment workers, mostly women, died in that fire.

I do not have enough space left even to present a very brief account of what happened after that. Almost the entire population of New York was on the streets to attend the funeral of those who had died. Laws were changed to prevent such incidents from happening again.

You may find it unbelievable how that tragedy captivated the minds of the people. Memorials were set up. Documentaries were made. Books were written. Songs that became popular were written and sung by leading performers. There was even a feature film. Plays were staged. Even in recent years, it was invoked in various contexts. (Go to Google, please.)

I was reminded of the Greek tragedy when I read about a forsaken Baloch woman’s encounter with death. Perhaps Pakistani society, in a collective sense, would be an appropriate character for a Greek tragedy.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer is a senior journalist. He can be reached at: [email protected]

Originally published in The News