Reform or relapse

If Pakistan fails to implement broad-based reforms, it may face another economic crisis once IMF programme expires

July 29, 2025

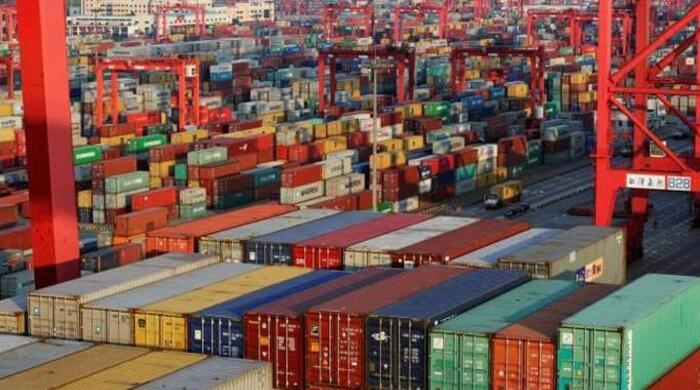

Pakistan has posted a $2.1 billion current account surplus in FY25, the highest in 22 years. Foreign exchange reserves have climbed to $14 billion, up from a dangerously low $3.5 billion just two years ago.

Notably, this improvement has occurred without a parallel increase in foreign debt, prompting many to hail it as a sign of macroeconomic recovery. These headline figures are encouraging, but they reveal only part of the picture; deeper structural weaknesses remain unaddressed.

The review of the external account clearly established the fact that the surplus has been driven primarily by an unprecedented $8 billion increase in remittances, reflecting the continued support of Pakistanis abroad. Modest export growth, strict fiscal controls and policy discipline — much of it under the IMF programme — have also contributed. Continued debt rollovers by friendly countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and China have also helped Pakistan avoid an external financing crisis.

Investor sentiment has improved, at least in the secondary market of the Pakistan Stock Exchange, where the KSE-100 index has surged past 130,000 points, and market capitalisation now nears $60 billion. However, this surge reflects short-term optimism rather than a genuine structural transformation.

But beneath these numbers lie serious concerns.

This surplus is not the product of improved productivity, robust exports, or a revived domestic economy. Instead, it reflects a combination of external inflows and internal economic suppression. Remittances, while critical, are not a sustainable substitute for domestic export capacity. Export growth remains concentrated in low-value textiles, and imports are depressed, not due to efficiency or substitution by domestic production, but due to stagnant demand and weakened purchasing power.

Private investment remains sluggish, and industrial activity is yet to recover. In effect, this so-called stabilisation has come at a significant cost — a cost borne by ordinary citizens.

According to the World Bank, poverty in Pakistan has risen to 44%, and unemployment exceeds 20%, particularly among educated youth. While headline inflation has declined, real wages have stagnated, and purchasing power continues to erode. Interest rates, though significantly down, remain in double digits, discouraging credit expansion and capital investment. Business confidence remains low, and risk appetite is muted.

This has created a precarious macroeconomic equilibrium. On paper, the government’s external accounts appear better, but the real economy is struggling and citizens are finding it difficult to survive.

Worse still, the apparent stability is neither homegrown nor durable. It rests on three fragile pillars: record remittance inflows, IMF-imposed fiscal controls (including a punitive tax regime that hinders growth), and external debt rollovers. None of these offers a reliable path to sustainable development.

If Pakistan fails to utilise this temporary window to implement deep and broad-based reforms, it may face another economic crisis once the current 37-month IMF Extended Fund Facility expires in October 2027.

The country faces substantial external repayment obligations in the coming years. Without meaningful gains in exports, investment, and savings, the question of debt sustainability will resurface. Pakistan has seen this movie before — a brief calm, followed by a crisis when the scaffolding is removed.

What's needed now is not just economic adjustment, but a fundamental restructuring of both the economy and the state's governance apparatus. At the heart of Pakistan’s recurring economic malaise lies a failure of governance across federal, provincial and local levels.

Key governance reforms in Pakistan must address several critical areas. First, public financial management needs a major overhaul to ensure that budgets are directly linked to measurable outcomes. This requires greater transparency, fiscal discipline, and a focus on achieving value for money in public spending. Second, public-private partnerships (PPPs) should be prioritised in sectors like education, health, population control and agriculture. By leveraging the private sector through outcome-based partnerships, the state can avoid the pitfalls of expanding inefficient and unaccountable public bureaucracies.

Third, civil service reform is essential. A merit-based, performance-oriented bureaucracy is vital for effective policy execution, whereas the current culture of politicisation, inefficiency and lack of accountability seriously hampers service delivery.

Fourth, judicial and contract enforcement reforms are urgently needed. Weak contract enforcement discourages investment and erodes public trust in the rule of law. Restoring commercial justice and legal credibility is foundational for sustained economic progress. Fifth, the tax administration must be overhauled to expand the tax base through equitable and technology-driven systems. This also means reducing reliance on regressive indirect taxes and cutting exorbitantly high rates that currently suppress business growth.

Lastly, empowered local governments are crucial for service delivery. Without functional and autonomous local bodies, it is impossible to provide essential services such as water, sanitation, waste management and local infrastructure. Devolution must be realised both in spirit and in practice.

At the same time, Pakistan must implement targeted economic reforms to unlock its potential. Export diversification is a top priority. The country's heavy reliance on textiles must end, with greater support extended to high-potential sectors such as information technology, pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, and agro-processing.

These sectors require assistance in branding, building compliance capacity, and gaining access to global markets. Improving the investment climate is equally critical. This involves ensuring policy predictability, rationalising taxation, improving regulatory efficiency and reinforcing legal certainty to attract both domestic and foreign investment.

In addition, capital market deepening must be pursued. The recent stock market surge should translate into real capital formation, which means incentivising IPOs and fresh listings through fiscal reforms, streamlined regulations and stronger institutional investor participation. The energy sector also needs urgent restructuring. Without a reliable and affordable energy supply, industrial growth will remain elusive.

Challenges such as circular debt, line losses, poor governance and high tariffs must be tackled head-on. Finally, investment in human capital is non-negotiable. Pakistan’s youth bulge could quickly become a demographic disaster unless immediate steps are taken to invest in education, healthcare, vocational training, and digital inclusion.

Finally, fiscal discipline must be internalised. It must be based on an innovative domestic agenda, not just IMF conditionalities. Sustainable outcome-based budgeting, targeted subsidies and inclusive safety nets must become part of a long-term national strategy, not emergency responses.

None of this is easy. These reforms require political courage, risk-taking, administrative capability and long-term commitment — all of which have historically been in short supply. But the alternative is worse: continued dependency on the IMF & co, deepening poverty and another cycle of collapse.

The $2.1 billion current account surplus is not a badge of economic success. It is, at best, a narrow window of opportunity. If used wisely, it can be the platform for renewal. If squandered, it will simply be remembered as another fleeting moment of calm before the storm.

Poverty has deepened. Unemployment has risen. Governance has further eroded. And the margin for error is now dangerously thin. Pakistan has already lost valuable time, with the first year of the IMF programme yielding little in terms of structural reform. The second year is not just another opportunity; it may well be the last viable chance to correct the course.

What we do now will determine whether we confront our foundational weaknesses with resolve or slide once again toward the next inevitable crisis.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer is a former managing partner of a leading professional services firm and has done extensive work on governance in the public and private sectors. He posts @Asad_Ashah

Originally published in The News