After the storm: hardship endures for Puerto Ricans on US mainland

Hurricane Maria, which made landfall on September 20, killed 2,975 people in Puerto Rico

September 19, 2018

They arrived in New York from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria ravaged the island in September 2017, leaving widespread devastation in its wake and a death toll that would spiral to almost 3,000.

A year on, Joannelly Cruz and her mother Gloria Martinez are in a homeless shelter, part of a generation of Puerto Ricans struggling to rebuild shattered lives on the US mainland.

But they have no plans to return to their Caribbean home.

"I think coming here was the best thing to do," says Joannelly, 16, reflecting on the catastrophe unleashed as the storm wiped out infrastructure and brought chaos rarely paralleled in US history.

But life is hardly a cake walk in New York, where mother and daughter share a bed in a small room with no access to a kitchen. Their belongings lie scattered on a table which doubles as Joannelly´s homework desk.

"It was a tough adjustment," she said. "It is kind of difficult to sit and do my homework in such a cramped environment, but I managed."

She and her mother hope to be considered for subsidized housing soon.

"Since we´re homeless by accident, they should put us in priority to get housing," Martinez says, anxious about a precarious future for her daughter with no safety net, and no certainties at all.

Indifference

Hurricane Maria, which made landfall on September 20, killed 2,975 people in Puerto Rico, according to a government-commissioned study, knocking out power and drinking water supplies, and causing $90 billion in damages.

The US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the body in charge of post-disaster aid, initially covered evacuees´ hotel costs but that program ended in May, triggering court rulings that kept it in place through the summer. Knowing it would end, many moved into shelters.

A spokeswoman for the City of New York told AFP officials expected to see some 700 Puerto Ricans in homeless shelters going into the anniversary of the disaster.

Government-sponsored, long-term shelter is not available to Puerto Ricans relocated to the mainland -- an option offered to previous hurricane survivors on the continental US.

Latino Justice, an organization leading a class action suit against FEMA, said that the policy violates the evacuees´ constitutional rights.

"We argue that it is FEMA´s responsibility to provide for those individuals," Natasha Bannan, an attorney with the lobby group, told AFP.

Many see FEMA´s response as a proof of a passive, indifferent attitude toward Puerto Rico from the administration of US President Donald Trump.

"They don´t understand the gravity of the situation we lived through," said Sofia Miranda, a 44-year-old former insurance broker and evacuee.

'Emotional crisis'

FEMA had offered to fly residents back to the island free-of-charge until August 30. Of the thousands displaced, just 500 or so accepted the offer, the agency said.

Miranda, who shares a room with her mother and son, is determined to stay, but says life in the shelter is taking its toll.

"As of now I´m in limbo. I haven´t been told if I´m eligible for housing, nor if I can stay in this shelter. I haven´t been able to sleep," she told AFP.

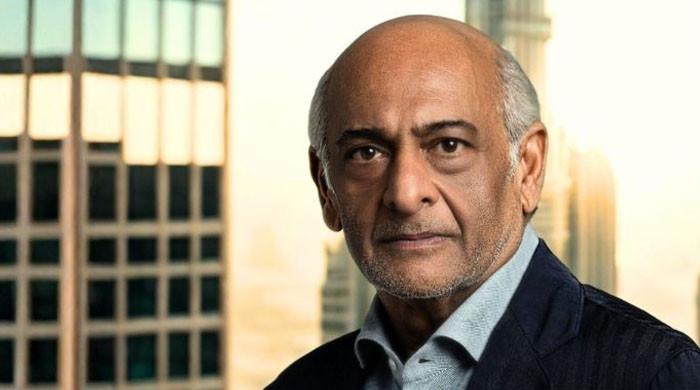

Rafael Barreto, an evacuee in New York since last November who does community work, spoke of the lingering psychological trauma weighing on displaced Puerto Ricans dealing with fresh stresses in their new home.

"There is an emotional crisis here after leaving this disaster. When there is strong wind, a lot of us here have flashbacks," he told AFP.

Meanwhile Leonell Torres, a clinical psychologist who has counseled displaced individuals, explained that each relocation was in itself a traumatic event that could act as a trigger.

"There is a misconception that being here is a guarantee for being healthy," he said.

In a report released on its website this summer, FEMA admitted to not being adequately prepared to handle the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, to being understaffed and to taking longer than expected to deliver supplies.

"Everything has been very complicated, frustrating, and the majority was thinking that because we are American citizens we would not be treated differently," said Barreto.