Politics and violence

Attacks on Imran Khan and Paul Pelosi remind us that violence is no stranger to party politics

November 16, 2022

The gun attack on former prime minister Imran Khan’s passing vehicles in Wazirabad and the home invasion and hammer attack on Paul Pelosi, the husband of the US Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, remind us that violence is no stranger to party politics.

Whatever the motive of either of these attackers, violent incidents cannot be considered unusual or atypical in 21st-century electoral politics. Assassination attempts are not new in politics, but in democracies, they should be a thing of the past. Where all sides have confidence that the losers will facilitate smooth transitions of power to the winning group, there is arguably little need for such violence.

People may be bitterly disappointed, but they understand that their turn will come at a future election. Pendulums invariably swing in the other direction, though sometimes the wait seems painfully slow in the context of party politics.

So what happens when the “losers” decide to obstruct the smooth transition of power and passionately engaged citizens lose faith in the electoral process? Perhaps we have seen what happens— politicians and the people near them get shot or attacked with hammers.

I have carried out research in northern Punjab for more than two decades and for the first 10 years, I focused on a cluster of villages in the Rawalpindi Division. I was interested in why there wasn’t more violence than was apparently visible.

To be sure, there is violence in rural Punjab. Anyone who denies that has stuck their head in the sand and must have the qawwali volume on 11.

But there isn’t nearly as much violence as there should be if you listen to the way men talk about conflict. Young men, in particular, can be especially volatile in their rhetoric.

Thankfully, this is checked in a variety of ways that typically go uncredited and even forgotten when we tell the tales down the road.

In 1999, when the Kargil Crisis was headline news around the world, I and my friends were nervously giggling about nuclear weapons being dropped on Kashmir and whether the fallout would drift over the Attock district in sufficient volumes to kill us all, I recall a young man boldly asserting that he was going to Kashmir.

He shouted, rather theatrically, that he would be a martyr while defending his Muslim brothers and sisters. I was assured later that his wife put an immediate stop to this bravado and reminded him he had small children and would do no such thing.

That sort of familial check on violent masculinity is critical everywhere, but perhaps nowhere more so than in circumstances where the state has chosen discourses of violence that both rely on and stoke individual ideas of violence and (typically masculine) honour.

If we were only dependent on sensible wives, sisters and mothers to curb the violent urges of their relatives, however, we would all be in trouble. Thankfully, villages across the world appear to have evolved systems to delay violence. It turns out that if we can just delay violence a bit, we wind up reducing it a great deal. So much of the violence that we experience in the world is driven by momentary passions that aren’t met with any sense check by those closest to the potential perpetrator.

Much of the conflict management that I was privileged to observe in rural Punjab seemed to exhibit a sophisticated strategy of delaying and deflecting.

The organisation of a jirga or a panchayat is involved and both institutions allow seemingly unrelated people to weigh in on the consequences of the disagreements.

While they can be heated and involve shouting and even threats, violence is not common during such proceedings.

Throughout the proceedings, conflicting belligerents are reminded that their disagreements affect many more people than them. They are given time to reflect on how their actions may harm those they care about.

Today, as we pick up the newspapers and wonder what horrific violence may have occurred since the last time we checked, I begin to wonder what’s happened to the village and family checks.

The man who broke into the Pelosi home must surely have neighbours and relatives who would have reminded him of the consequences on his loved ones of such a mindlessly cruel act.

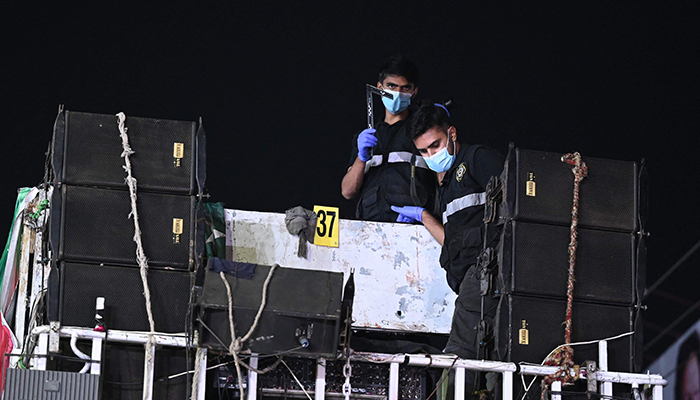

The man who sprayed bullets at a former prime minister and those nearest him must equally have people around him who could have told him they will suffer for his singularly violent outburst.

Just as those systems of checks took generations to develop and establish themselves in villages, the erosion of such checks at the political party level has been in the making for several years now.

If the leaders of political factions lose faith in political processes and refuse to accept the outcomes of democratic elections, then it is no surprise that their most committed activists follow suit.

When that happens, the patience required to wait for the political pendulum to swing back its way becomes so thin that there is no way that disagreement can be deferred long enough to avoid violence.