High stakes: Mountain tourism in a warming world

Study shows fragile mountain ecosystem of GB severely affected by extreme weather and climate-related hazards

July 17, 2025

KARACHI: “It started with a thunderous roar in the distance, followed by the clatter of rocks grinding together,” said Mohammad Hussain, 26, a student, who witnessed the flash flood that hit the lakeside of Attabad on June 25, around 12:30pm, in the mountainous Hunza Valley, a popular tourist spot in the northern part of Pakistan’s Gilgit Baltistan (GB).

Standing atop the Moon Bridge, he saw a muddy slush surging at high speed; the sloshing sound came with dull thuds as boulders slammed into the earth. “I was both scared and awestruck,” he told IPS over the phone from Hunza.

The valley had been experiencing unusually high temperatures that week. “We’re mountain folks — we can bear the cold, but not such intense heat,” he said.

Such erratic weather patterns reflect a broader trend.

A 2024 study shows that the fragile mountain ecosystem of GB is severely affected by extreme weather and climate-related hazards like floods, avalanches, landslides, and glacier lake outburst floods (GLOFs). With 50% of the 72,971 km² land considered cultivable, the predominantly agrarian community uses just 2% to farm on small plots averaging 0.4 hectares per household. Reduced snowfall has led to water shortages and reduced grazing ground, increasing food insecurity in the region.

Experts warn that no construction should ever be carried out in a natural drainage path or catchment outlet. While these areas may appear stable for decades, a sudden intense flood can lead to devastating consequences. High-risk zones include ravines and low-lying veins that channel rain and meltwater.

Khadim Hussain, director of Gilgit Baltistan’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), explained that the heatwave had caused rapid snowmelt in the mountains, swelling the Burundubar stream and triggering a flash flood.

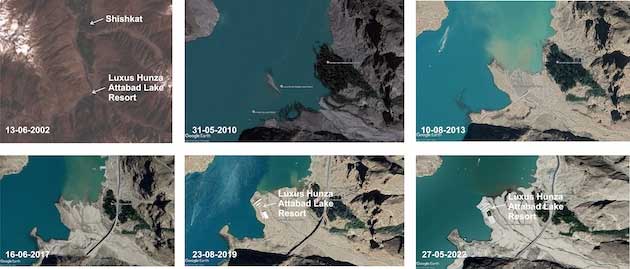

The resulting sludge flowed into Attabad Lake—a lake formed in 2010 when a massive landslide dammed the Hunza River, submerging Ainabad village and partially submerging Gulmit and Shishkat.

“The sludge engulfed the Luxus Hotel from both sides, cutting off access and trapping tourists and staff,” said Zubair Ahmed Khan, assistant director at the Gilgit Baltistan Disaster Management Authority for Hunza and Nagar, two high-risk disaster-prone districts of GB.

He has been provided with an excavator and its operator, but the authority had to seek help from boatmen operating in the lake to rescue about 150 stranded people in time from inside the hotel, he told IPS.

Since the hotel began operating seven years ago, the Burundubar stream has flooded only three times—”twice this year,” informed Khan, adding, “The future remains uncertain.”

The experts already foresee the situation worsening.

“As the climate changes, the frequency and intensity of floods in Burundubar have increased, leading to the accumulation of debris in the flood path. This has significantly raised the risk to surrounding infrastructure,” said Shazia Parveen, an environmentalist from Hunza.

She warned that the area, being in a high-risk flood zone, risks losing existing infrastructure and must be declared an Ecologically Sensitive and Critical Area (ESCA) under Gilgit Baltistan’s 2023 rules.

A post-flood assessment report commissioned by the GB government concluded that the Burundubar stream posed a “recurring risk of high-intensity flooding endangering the hotel structure, staff, and tourists”.

Vaqar Zakaria, head of the Islamabad-.based environmental consulting firm Hagler Bailley Pakistan, said floodplain management laws exist but are rarely enforced.

“Our response is always reactive — panic after the damage, but never a plan to prevent it,” he said. While acknowledging worsening climate impacts, he argued that “90% of the damage is avoidable with proper planning and regulation”. This failure, he added, is why international donors often ignore Pakistan’s climate pleas: “We never admit to poor planning or the blatant disregard of our own laws.”

The consequences of such neglect are visible.

“The Luxus hotel sits in a flood path — it should never have been built,” said local activist Jameel Hunzographer, blaming the government. “The lake was once so clean you could drink from it—no longer.”

But not everyone shares his concern.

“It [the hotel] may be submerged,” admitted 60-year-old Dervaish Ali, “but it will never collapse.” Once a farmer from Ainabad, whose 16-acre orchard was swallowed by Attabad Lake, Ali later turned to construction—and was contracted to build the Luxus hotel. In 2017, he sold — 0.62 acres to the hotel’s owner and used the proceeds to build a home 25km away, safely outside the hazard zone.

Firmly distancing himself from any blame, he said, “When I sold the land to the owner, he was fully aware of its precarious location, and I was not the only one; several others sold their land too, in the same area.” He acknowledged, however, that the increasing intensity of flash floods—driven by climate change—destroyed the 300 poplar trees he planted near the hotel, on his leftover land, just two years ago.

“Every last one gone,” he said quietly.

Yet, for many activists, this damage is part of a larger pattern of reckless development.

“These flash floods and disasters are of our own making,” said Baba Jan, 48, president of the Gilgit Baltistan chapter of the left-wing Awami Workers Party. “We’ve turned the region into a concrete jungle and call it development.”

Jailed for ten years in 2011, he had protested “carving mountains, dumping waste into waterways, altering stream courses, and polluting our air—all in the name of tourism.”

Hunzographer also flagged the alarming rise in tree-cutting—clearing land for construction and chopping wood for fuel, due to the lack of electricity and gas.

Opened in 2019 on the shores of Attabad Lake, the Luxus hotel has recently come under sharp criticism from locals—not only for its unsustainable practices and careless approach to hospitality but also for its controversial location. Still, many residents were unwilling to speak on record, fearing reprisals from the hotel’s politically well-connected and influential owners.

President of the Sustainable Tourism Foundation, Aftab Rana, expressed disappointment with the Luxus and other hotels along the Attabad Lake, saying they had the potential to set a “benchmark for sustainable luxury” in the region. Instead, they have become a “symbol of environmentally damaging development”, placing both guests and staff directly in the path of climate-related hazards. He blamed the Environmental Protection Authority for failing to manage the lake’s tourism-related environmental impact.

He has a point. If not for a viral video last month by British vlogger George Buckley exposing the Luxus Hotel’s violations, the GB government might have stayed asleep. But after the video gained traction, authorities acted — partially sealing the hotel and fining it for allegedly dumping wastewater into the lake, a charge the resort publicly denied. Yet, it paid the fine, effectively admitting guilt despite its claims. A post-flood assessment also cites the hotel’s repeated disregard for environmental warnings, confirming violations of environmental laws.

The GB EPA has recommended a five-year ban on hotel construction and/or expansion in various parts of GB, including Attabad, citing unregulated development and lack of wastewater treatment, which is harming public health and the ecosystem.

In addition, the deputy commissioner (the administrative head) of Hunza has taken an unconventional step – exercising the powers conferred on him under the law “in the interest of environmental protection, public health, ecological preservation, and sustainable tourism” has put a complete stop to “new construction or extension of any kind” by suspending issuance of no objection certificates in parts of Hunza, including the Attabad area.

The constant roar of diesel generators from hotels and restaurants, the smoke-belching vehicles, motorised boats churning toxic fumes into the lake’s air, and the rising dust and noise from throngs of tourists—combined with heaps of plastic waste—are fuelling a growing love-hate relationship between locals and visitors.

“We’re exhausted by tourists, but we depend on them,” said 33-year-old Nur Baig, who runs a co-working space in Hunza. Tourism in Hunza surged after photos of the newly formed Attabad Lake went viral, but the government failed to plan for the influx. For instance, he points out that there are no footpaths, and speeding SUVs now threaten pedestrians, especially children, on the narrow streets.

“We either need a different breed of tourists, who are more respectful of nature and us, or we need to put a stop to tourism,” said Hunzographer.

But there is a deeper shift within the community itself, where economic pressures and changing aspirations have left local people struggling to maintain both their traditions and control over their land.

“The younger, educated generation has turned away from subsistence farming, with the more enterprising moving to urban centres for better livelihood opportunities,” admitted Baig, adding, “Those who stay have ideas but little capital, so outsiders come, cash in, and take our peace with them.”

But not all hope is lost. Amid these changes, some see a path forward — one where tourism benefits locals without costing them their way of life.

A local NGO, Karakoram Area Development Organisation (KADO), for instance, is pushing hotels to swap single-use plastic for reusable fabric bags—and selling them too.

“We carried out a study and found that although there was enough awareness about plastic waste among the locals, the waste jumped to 67 percent in peak tourist season in Hunza,” said Abbas Ali, who heads KADO.

“We’re doing our part,” he added, “But tourists must realise our waste systems are limited—this plastic ends up in our water. They need to share responsibility.”

Rana also believed luxury and sustainability can coexist. With young travellers demanding greener options while their stay is comfortable, governments across the globe are stepping up with stricter rules on energy, emissions, and waste.

In Pakistan, though, he said, “Customer pressure may be growing, but enforcement remains missing.” If hoteliers saw green practices as smart business, he said, they would realise measures like water-saving fixtures, dual-flush toilets, rainwater harvesting, energy-efficient lighting and more can cut costs significantly.

For its part, Rana’s STFP has developed sustainable mountain architecture guidelines, and the government’s Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation has come up with a hefty document on national minimum standards and guidelines for the tourism and hotel industry and shared it with different provincial governments.

“But neither the tourists nor the hotel industries are really interested in adopting standardised green certifications due to a lack of necessary enforcement by the concerned provincial government departments,” he lamented.

Zofeen Ebrahim is an independent journalist. She posts on X @zofeen28

This article was originally published in the Inter Press Service news agency's UN Bureau. It has been reproduced on Geo.tv with permission.