From the Afghanistan files

Gen Akhtar saw Afghanistan as Pakistan's forward line of defence against Soviet Union and, to some extent, against India

August 17, 2025

It was on the BBC World Service at 7pm Riyadh time on December 24, 1979 that I heard the news that the Soviet Union had invaded Afghanistan. The operation had begun about three hours earlier as darkness fell in Kabul.

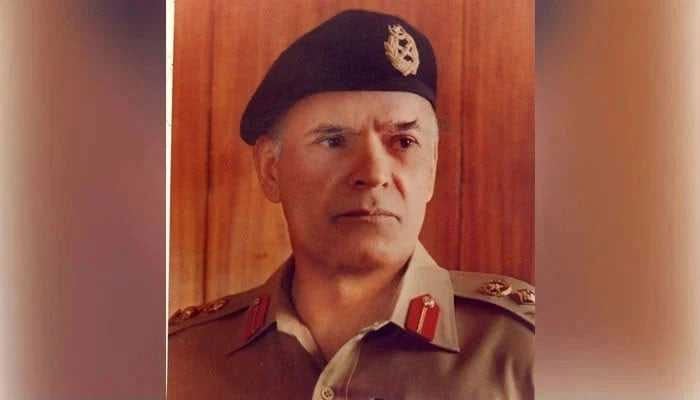

The first substantial reaction to the invasion occurred in Pakistan, which was natural enough given that Pakistan was the neighbour of Afghanistan and the country that was going to be most affected by events. It was on the day after the invasion that President Zia sent for his Director General of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), General Akhtar Abdul Rahman Khan, and asked him to prepare an "Appreciation" of the situation, with recommendations for action.

General Akhtar produced his report within days. He was immediately concerned that the Soviet Union, an atheist power, had invaded a Muslim country to back socialist leaders whose declared purpose was to establish a secular, indeed Communist, state.

Neither he nor General Zia feared that this would undermine the religious nature of Afghan society, but it seemed to Akhtar that Pakistan was morally obliged to defend Islam in its neighbour.

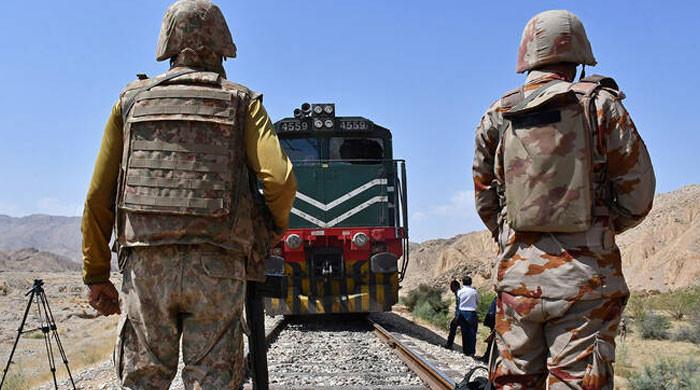

He also had military concerns. He was very much aware that once the Soviets gained control of Afghanistan, which they seemed bound to do, their forces would be in the southern provinces of Kandahar and Helmand, bordering Balochistan, and Balochistan was the province they would need to subvert or invade to reach the sea.

Another fear concerned how Pakistan might be affected if a Communist government in Kabul were to establish close relations with the government of India, which at that time had excellent relations with the Soviet Union. Akhtar could see that in the event of another war with India — there had already been three between the two powers — Pakistan could find itself threatened from two sides.

Even in less extreme circumstances, an Indian-Afghan alliance could put pressure on Pakistan by increasing the armament of the Pakistani tribes on the North-West Frontier, which would increase their already strongly independent instincts and defiance of central authority.

Given that Afghanistan had never accepted the border between itself and Pakistan in that area, the subversion of the frontier tribes could easily be followed by a claim to a slice of the North West Frontier Province. Akhtar saw Afghanistan as Pakistan’s forward line of defence against the Soviet Union and, to some extent, against India. He recommended forcefully to his president that Pakistan should back the Afghan resistance, which had already been operating for some years against the socialist regime.

General Akhtar argued for a large-scale guerrilla war, aimed ultimately at defeating the Soviets. His plan involved Pakistan supporting the guerrillas with arms, money, intelligence, training, operational advice and — above all — the offer of the border areas of the North-West Frontier Province and Balochistan as a sanctuary. For any guerrilla movement, a safe haven is enormously important. In this case Akhtar was turning to the advantage of Pakistan and the resistance the wild nature of the border, which might be exploited by the country's enemies if Afghanistan were to come under hostile control.

Very soon after he read the "Appreciation", President Zia telephoned King Khalid to say he wanted to send General Akhtar to Riyadh. He arrived in the first few days of January 1980. I remember we went straight away to pay calls on the King and Crown Prince Fahd. We met in what had been my father's private office, next to the entrance of his palace. Later in the day Akhtar and I had a long discussion in my office and then, on what I remember was a very cold evening, we had dinner with my secretary, Ahmad Badeeb, at the Al Khozama Hotel.

I must say I liked Gen Akhtar. He was a big Pathan, fair in complexion, pleasant and cheerful — and he struck me as a very straightforward and loyal colleague of his boss. His message from General Zia was that Pakistan was already playing host to several Afghan political parties and embryonic guerrilla organisations — some of them established in the time of Mohammad Daoud.

It was intending to back these guerrilla groups in a war against the Russians — and it needed help, financial and material. General Akhtar spent only two days in Riyadh, and we decided to help straight away. It was only a few days after he left that we sent Ahmad Badeeb with substantial financial support to Islamabad.

Ahmad went straight to the President’s residence, where he met General Zia and General Akhtar again. Ahmad got back to Riyadh late that night.

A fortnight later I went to Pakistan myself, with my brother Saud AlFaisal, our foreign minister — God rest his soul. The occasion was the meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in Islamabad on 27–29 January, but we went a day or two earlier for a private meeting with Zia and Akhtar. This was my first meeting with Zia — the first of many as it turned out.

The four of us meeting in Zia's house agreed that it seemed to be the Soviets’ intention to reach the Indian Ocean, and we promised each other that we would do our best, as we put it, "not to allow Pakistan to become the next Afghanistan".

Our resolution was reinforced by the Islamic foreign ministers in the next two days. The conference was one element of a broad international movement against the Soviet invasion. There was widespread international concern about what seemed to be the USSR's expanding ambitions in the Indian Ocean basin. The Americans were particularly concerned because, less than a year before, their major military ally in the region, the Shah’s government in Iran, had collapsed and been replaced by an Islamic republic which was admittedly strongly anti-Communist, but much more passionately anti-American.

From the beginning of the war against the Soviet invasion force the task of managing the Mujahideen groups, in so far as this was possible, was left to the Pakistanis. And the people who had most influence on the overall strategy of the war — on the theatres of action, the intensity of operations and the allocation of supplies — were President Zia and the chief of the ISI, General Akhtar Abdul Rahman Khan.

The two were masters of the game. They showed great attention to detail, perfect judgement, diplomatic finesse and caution. The game was not an easy one. If they overplayed their hand and provoked the Soviet Union too much — or alternatively if the Soviets found themselves quite easily able to control Afghanistan — there was the ultimate danger of a Soviet attack on Pakistan itself. General Zia said to General Akhtar immediately after the invasion, "The water in Afghanistan must boil at the right temperature".

The challenge for the allies of the Mujahideen was to make our help as effective as possible. In the early years our system of distributing aid and weapons was made less effective than it should have been by the fragmentation of their forces. The ISI began by giving arms to individual commanders, most associated with one or other of the seven parties, but many operating completely independently.

It was subsequently decided to stop issuing supplies to individual commanders and to have everything in future channelled through the parties. This was easier said than done.

Akhtar found it impossible to get any form of agreement among the parties on what quantities of aid and munitions each deserved, which areas should be their spheres of operations and how they might co-operate in a military sense. Some of the leaders would not even sit in the same room with each other.

Akhtar persevered. By early 1984, he had decided that there had to be some sort of alliance between the parties to create a recognised high-level body that could act at least nominally to allocate arms and money, and through which the Afghan Bureau could attempt to coordinate some of the action inside Afghanistan. For weeks, Akhtar argued with the leaders in vain. He asked me to come to Pakistan to address them, which I did willingly — to no avail.

President Zia lent himself to the task, but still found the leaders recalcitrant — and then his patience snapped. At 2:00am one day, he issued a directive that there was to be an alliance of the seven parties and that they were to issue an announcement to this effect within seventy-two hours.

The leaders knew that without Zia's backing they were finished — so they formed an alliance, though even now Hekmatyar insisted that all important decisions be made unanimously, not by majority vote. From now the Arms Pipeline, as it was known, operated on a stable and effective basis until close to the end of the Soviet occupation in 1989.

In 1985 and early 1986, the fighting in Afghanistan grew fiercer still. The ISI concluded the Mujahideen would have done better if they had built proper defences in the way they had been advised to do months before. It also decided, not for the first time, that the fighters needed a good surface-to-air missile — something better than the Blowpipe, which had proved useless in this battle.

The obvious answer was the Stinger missile — a new, highly effective, lightweight weapon which was fired from the shoulder. It had already been mentioned on several occasions in our discussions, and Pakistanis raised the matter seriously when they reviewed the situation with the Americans at the end of 1985.

The Stinger had been issued to American forces in 1981, but it had never been used in battle and its technology was still secret. The worry was that if it were used in Afghanistan it would sooner or later end up with the Soviets, through being captured or perhaps being sold to a KHAD agent.

It might also be acquired by the Iranians or even find its way into the hands of a terrorist group. President Zia himself was nervous about assassination – there had been several attempts on his life – and he was concerned about the missile being used against his own aircraft. In the end what tipped the balance in favour of supplying the missile was the big Soviet offensive near the border in April 1986.

President Reagan authorised the supply a few weeks after this and Pakistani instructors flew to the United States for training in June. In September 1986 the first Mujahideen unit equipped with Stingers went into Afghanistan. The Stinger tipped the balance of the fighting in favour of the Mujahideen.

Some months after the Geneva agreement, as the final withdrawal of troops was being planned, the Russians became concerned about the movement being carried out in an orderly fashion without too much harassment by the Mujahideen. They wanted to save the lives of their troops and, equally important, save face. They were telling their people at home that they were withdrawing because their forces had finished their job, and it would not look good if troop convoys were destroyed en route and the whole affair made to look like a defeat. Nothing had been said at Geneva about the way in which the withdrawal would take place.

Since the agreement, the Russians had made it known to the Mujahideen that if their troops were attacked, there would be very heavy retaliation – but they wanted to get some sort of diplomatic agreement on this as well. The Americans were obviously not likely to co-operate.

It may be that the Americans were partly responsible for the removal of Akhtar Abdul Rahman Khan from command of the ISI in March 1987. He was promoted to full general and made Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee. Akhtar had been firmly against American proposals to change the arms-supply system, and he was regarded by the Americans as the champion of the fundamentalists.

Also, he had a few friends at the top of the Pakistani military establishment. He was regarded by the other generals with envy and suspicion, and he did not get on with the Prime Minister. President Zia could have resisted all these pressures, but now that victory was within sight, possibly he did not want any Pakistani other than himself taking too much credit. So Akhtar went, and was replaced by Lieutenant General Hamid Gul, who had been Director of Military Intelligence at General Headquarters.

In April 1988, almost coinciding with the signing of the Geneva Accord, there was an explosion at Ojhri Camp in Rawalpindi which destroyed the entire stock of arms and ammunition held there. It emerged at the subsequent enquiry that a box containing rockets fell from a pile of other boxes and caused a small explosion.

It seems that contrary, to all regulations, the rockets had been armed with fuses before being shipped. The explosion injured several people, and during the rush to evacuate them nobody bothered to extinguish the small fire it started. Ten minutes later the entire ammunition dump went up. It is still not known if the explosion was the result of incompetent handling by a loading party or was caused by sabotage.

A final disaster that year happened in August, when an aircraft carrying President Zia, General Akhtar and the US ambassador and military attaché crashed on a flight from a Pakistani military camp back to Islamabad, killing all on board. No definite evidence of the cause ever emerged, but on this occasion it certainly looked like sabotage by the KGB or KHAD. So, in one way and another the Soviets got the trouble-free withdrawal they wanted.

Much changed in 1989, the year of the Soviet withdrawal. Up to this point, the three foreign partners backing the Mujahideen had generally worked rather well together. We had all wanted to push the Russians out of Afghanistan and remove the Communist regime. And the personalities involved had been more or less the same — President Reagan, William Casey and then Robert Gates at the CIA, President Zia and General Akhtar Abdul Rahman Khan, King Fahd and myself.

Now our interests diverged — not completely, but it became clear that we had different emphases and in the United States and Pakistan there were new leaders.

The denouement for the Soviet Union as a whole came very soon after the withdrawal from Afghanistan. In the autumn of 1989 all the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe collapsed and in November, the Berlin Wall came down. In August 1991, Gorbachev’s rivals attempted a putsch in Moscow.

For forty-eight hours, things hung in balance, but in the end it failed. On 24 August Gorbachev resigned as leader of the Communist Party and disbanded the party organisation. On the same day Ukraine declared itself independent from the Soviet Union and one by one the other thirteen republics that made up the USSR broke away.

On 25 December 1991, twelve years to the day after it invaded Afghanistan, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Gorbachev resigned as President. The Red Flag was hauled down on the Kremlin, and the white, blue flag of Russia was run up in its place.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

This article is based on excerpts from the book 'The Afghanistan File' by Prince Turki Al-Faisal Al Saud.

The excerpts have been compiled/edited for the article by Taimur Khan.

The writer was the director of Saudi General Intelligence Directorate from 1977 to 2001.

Originally published in The News