A vanishing global order

There is a semblance of order, but it is based on the dictum that might is right

August 30, 2025

The international order, as we knew it, may be in its death throes but the disorder we see around is not the birth pangs of a new international order.

There is a semblance of order, but it is based on the dictum that might is right, and that no foreign policy is sacrosanct or taboo anymore. Power has substituted principles. The UN never had any real authority to enforce peace or settle disputes, but did try to exercise some moral restraint. Even that has gone.

The international order was created and maintained by major powers, particularly Western powers, to preserve some measure of order and stability that would allow them to pursue their economic and strategic interests.

A degree of global security was essential to ensure peaceful conditions in which the West’s capitalist economy could prosper. The world also needed financial stability, and that was provided by the US-dominated international financial institutions.

Developing countries also benefited, but this depended on the quality of their governance. Where the governance failed, the countries blamed the West and their colonial past.

The end of the cold war and the emergence of many new capitalist oriented markets, freshly liberated from the grip of Soviet communism, the modernisation and opening up of China, the rise of computer technology, information revolution, the relaxation of immigration policies, deregulation, the liberalisation of the financial markets, and the ease of movement of capital across the globe produced globalisation.

As its economic growth was dependent on the global economy, the West promoted globalisation to help other countries, especially China, to grow economically, which would in turn help the West.

The exponential rise in foreign direct investment, combined with the WTO, helped not only China’s phenomenal peaceful rise but also global prosperity. And since peace and stability were essential to global prosperity, America did try to be the security provider of sorts.

However, the unipolar moment presented a temptation, and 9/11 offered a strategic opportunity to overreach. We live with its consequences now.

Significant historical changes are rarely caused by a single event. They are often the cumulative effect of slow-motion changes that reach a critical mass with a catastrophic event, transforming the world. 9/11 was such a moment whose significance we are only now beginning to grasp fully.

Americans are fond of saying that 9/11 changed the world. Actually, the world had been changing for a long time. It is just that Americans did not notice it. But they are right, 9/11 changed everything.

The irony is that they are the ones who were the prime instigators of change with unnecessary or unavoidable wars that broke many norms and brought grievous harm to the international order.

The US response to 9/11 was inspired by a religious outlook and driven by a supreme consciousness of power. America simplified and distorted the emerging global challenges and devolution of power.

These far-reaching changes may have made the US the sole superpower, but ironically also raised the status of other powers with competing interests and policies.

This made it hard for the US to lead, tempting it to dominate and resort to unilateralism, as in Iraq, which, in turn, provoked strong reactions and resistance. American power, therefore, was not absolute. And, on many issues, the US was walking alone, making its power even less absolute.

Contrary to the prevailing view that the Iraq war, and to some degree the Afghanistan war, were neocons’ wars, they were in fact the cold warriors’ – Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney and Condoleezza — wars.

They basically wanted to take advantage of the unipolar moment and establish America’s advanced presence in the Middle East and Central Asia while China and Russia were not yet America's military peers. It was a vain attempt by America to forestall China and Russia’s future influence in Central Asia and the Middle East. Both wars failed.

As America’s post 9/11 wars started failing, it had a domestic backlash against the elite, especially the new breed of global elite created by globalisation, which caused a concentration of wealth in their hands.

Globalisation caused job losses among the lower classes in the industrial heartland of America. And there was a populist outcry against China, where people saw their jobs and factories going.

The West then changed the rules. The rules-based order became exclusively a Western-based international order aimed at putting China at a disadvantage and limiting its rise. The US’s exceptionalism demanded exceptional treatment.

The rules were whatever suited the West at any particular time and whatever protected its interests. This led to unilateralism, which evolved into ‘America First’ under Donald Trump. The UN lost its relevance.

Separately, the US had been working ever since the end of the cold war on preempting a future resurgent Russia to establish its dominance in Europe. It did so by expanding Nato and offering countries like Georgia and Ukraine the prospect of Nato membership. And we saw where it led us: the occupation of Crimea in 2014.

Russia did what it may have wanted to do anyway, but used the security issue as a justification. Not once but twice, when it later invaded Ukraine. The fact is, there is no such thing as justified aggression, invasion or occupation. It is a violation of international law, whatever you may want to call it. Aggression is not defensible.

The big powers are not the only culprits. The US’s obsession with competition with China led to the nurturing of regional influentials as allies who were trying to take their own pound of flesh. They were using military power and intelligence capability enhanced by Washington to establish their own regional hegemony.

India is a prime example whose aggressive behaviour has been incited by a calculation that it could get away with anything due to the West’s fascination with it, fostered by the policy of containing China.

At least this was the case until Trump, in his second term, devalued the allies by laying down new terms of geopolitics that deemphasise wars. But the flip side is that his isolationism has boosted aggression by regional powers.

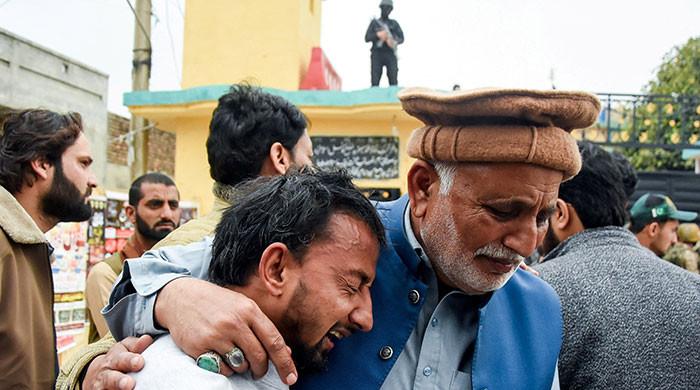

Arguably, no region has suffered from wanton aggression as much as the Middle East. The brutal dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, in partnership with Russia, had brought untold misery to the Syrians. But there is no contemporary parallel to the way Gaza’s killing fields have turned the place into the deadliest on the planet.

The horrific starvation and killings continue with increasing inhumanity in Gaza, shamelessly described by the Western leaders as Israel’s right to self-defence. Not to mention Israeli aggression against Iran that evoked no international censure, setting up a dangerous precedent. Anytime Iran tries to reconstitute its nuclear programme, it will be attacked.

Elsewhere, the bombings in Ukraine by Russia continue unabated, as does Indian Prime Minister Modi’s incendiary rhetoric, hurling existential threats against Pakistan and using water as a weapon. And the Afghan Taliban are committing aggression against their own people, especially women, and joining India in trying to destabilise Pakistan. One is losing hope in global peace and stability.

The UN is facing a serious crisis following the US’s withdrawal of approximately $1 billion in allocated funds, as well as uncertainty over future contributions from the US and other powers. And great powers are in gridlock, rendering the UN ineffective. It has played no role in stopping the wars in Ukraine, Gaza or the India-Pakistan conflict.

With the UN sidelined, peace-making has become a freelance activity by Donald Trump. And where he can play no such role or does not want to, he has let the aggressors dictate peace on their terms and play by their own rules.

Neither Trump’s America nor groupings such as BRICS and SCO, or other multilaterals or mini-laterals, by themselves will help the middle and small powers to cope with the shifting geopolitics and threats to peace.

They will have no option but to align or have a working relationship with all great powers and navigate their rivalries carefully without becoming a foreign policy instrument of one or another. For lack of better alternatives, this could be the best-case scenario for a future international order, for now.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer, a former ambassador, is adjunct professor at Georgetown University.

Originally published in The News