Pakistan's education financing—a glass half empty?

'There are urgent needs that cannot be ignored if Pakistan aims to achive the fundamental right to education for children as per Article 25-A of the Constitution'

May 25, 2017

On March 28, 2014, the Prime Minister of Pakistan Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif publicly announced his commitment to raise the education budget to 4% of the GDP by 2018. His commitment was later reinforced when he endorsed the proposals of Gordon Brown, the United Nations Special Envoy for Education, during his visit to the UN General Assembly in September 2014.

But, in 2017, the allocation for education in Pakistan hovers around 2.83% of GDP, a climb from 2.59% in 2013-14, which, at best, can be called a marginal increase.

For the year 2016-17, the total education budget (four provinces and federal combined) was Rs.790.704 billion as opposed to Rs.579.815 billion in 2013-14 – a rise of Rs.210 billion in four years.

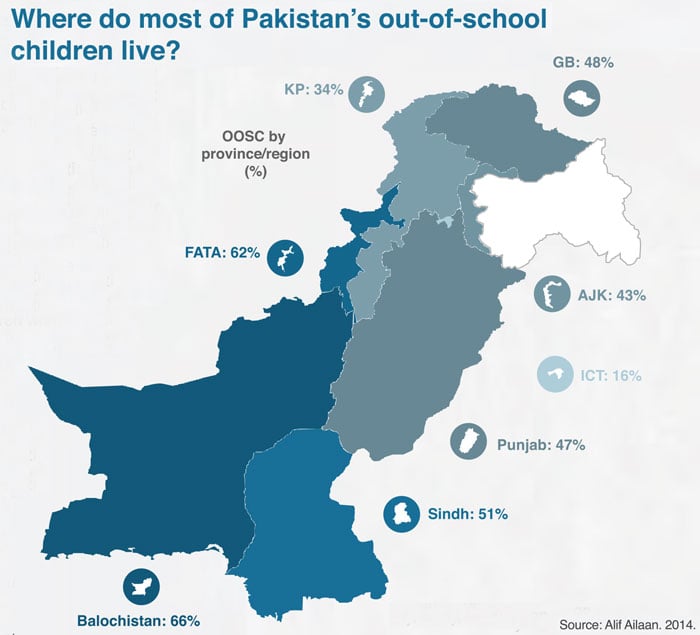

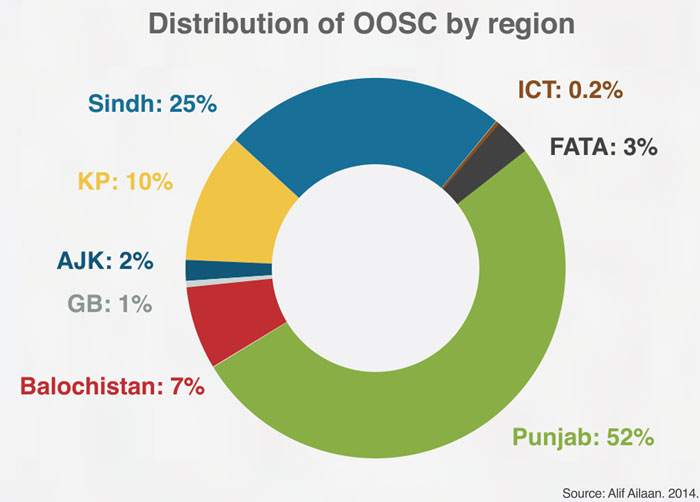

To seek comfort from the margins, we now have 22.6 million 'broken promises', according to Alif Ailaan, instead of 25 million children (ages five to 16) out of school two years ago.

At the cusp of another general election, it is important for Pakistan to be reminded of how the promises made in the manifestos of Awami National Party (6%), Jamaat-i-Islami (5%), Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (5%), Pakistan Peoples' Party (4.5%), and the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (4%) remain unfulfilled.

So, is education really a priority for the political parties or is it simply a vote-gaining rhetoric? Will the public continue to sustain this political trait in 2017-18?

With education completely devolved to the provinces since 2010-11, where does the responsibility lie?

The provinces can boldly spend what they allocate and ask more from the federal government as special grants for education through various constitutional forums of the prime minister, chief ministers, and ministers of education. But sadly, that day is yet to come, as provinces continue to underspend what they budget for education and other social sectors each year.

The 'tragedy' is witnessed each year from April-May, when media attention is drawn towards the underspending of development budgets.

For example, a recent a news article talked about 'Zero utilization of budgets in 346 schemes of education and health in Sindh', which led donors and stakeholders alike to seek explanations.

In spite of progressive budgets, both on regular (current non-salary) and development side (20% of provincial budget), utilisation remains meagre. After declaring an emergency for the sector, the government was urged to push for the timely use of Rs. 13 billion allocated for development budget and large amounts for the non-development recurrent side as well in Sindh.

For almost 68% of the development schemes (270 out of 396), not a single penny has been spent as of May 2017.

Sindh, like other provinces, has committed to sector-wide improvements from early childhood education to primary, secondary, post-secondary, and higher education, as well as backing for vocational programmes and support for out-of-school children, all of which, together, is reflected in the well-thought-out provincial education sector plans.

Even if utilization is achieved in May-June 2017 by some extraordinary effort, the quality of expenditure would remain compromised at best.

This pattern is not exclusive to Sindh – which has boldly explored numerous techniques, including PPP's Education Management Organizations (EMOs) and 'innovative initiatives' (Rs. 500 million) budget line in FY16-17 – but, like all provinces, it must also bear the responsibility for 'utilisation delayed = entitlements denied'.

Is that just?

Until March 31, the education department in Punjab could only spend 38 and 23 percent, respectively, of the Rs. 41.75 billion revised and Rs. 962 million special education allocations.

The development budgets and recurrent/regular non-salary that offer the most stability, sustainability, and progress, therefore, remain the most underutilized across Pakistan, painting a gloomy picture.

In Pakistan's education finance architecture, between 90% and 92% of the core budget originates from the government's own resources, supplemented by nearly 8 to 10% from the development partners.

This is a strong position for Pakistan on the basis of official development assistance (ODA) for value addition, but dilution occurs with weak ownership and politically whimsical spending.

There are urgent needs that cannot be ignored if the fundamental right to education has to be achieved for children between 5-16 years of age as per Article 25-A.

Seven areas make a business case for education:

1. More post-primary education facilities – currently 80% are primary schools – or middle and secondary schools for children to have 10-12 years of basic schooling. This can be done by upgrading existing schools, constructing new ones or through public-private partnership models successfully tested by the education foundations and school education departments (Punjab/Sindh) expanded to other provinces

2. Expanding comprehensive support to early childhood education programs (delivery and teachers) for successful entry/transition to primary grades, as is well-established in sector plans, laws, and policies. However, it currently suffers from weak implementation and institutional systems

3. Investment in:

a. Quality – teacher adequacy (K-12) and preparation/training and support

b. Curriculum reviews, language development and support (mother tongue/Urdu/English), textbook production protocols via multiple channels; transparent assessment/examination systems and consistent investment in technology-enabled learning for better outcomes

4. Technical and Vocational Education Training integration and inclusive education within mainstream education planning and budgeting

5. Stronger linkages to and investments in higher education and research

6. Commitment to innovation, inclusion, partnerships, and innovative financing to achieve 'Sustainable Development Goals 2030' and 'SDG 4' on education. Education cannot be divisive and unbalanced any more, since demand is exceptionally high, but supply and governance arrangements are unable to keep pace with strong commitment to education as a key public good.

The budget for education and its utilisation – note that the headline mentions 'a glass half empty' – can be reversed swiftly with public will and constitutionally-backed fundamental rights.

Article 19-A of the Right to Information law – which highlights the compulsory need to track budgeting of public goods, such as education, health, nutrition, shelter, clean water, and sanitation – should be displayed boldly in departments and ministries and, more importantly, in departments and ministries.

This information should be made user-friendly and repackaged for accessible public consumption in order to make utilisation trackable each month at the provincial, district, and local levels.

Let each school have its budget displayed boldly on its walls, gates, and noticeboards as allocated and received. Let budget action begin from the basic level – the demand to meet supply directly – without any interference from political slogans.

Baela Raza Jamil is the CEO of Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA) and Commissioner for the International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. She can be reached at [email protected]

NOTE: The views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News or the Jang Group.