The Pakistani 'Sangh Parivar'

With different sources of inspiration, Jamaatud Dawa and India's Sangh Parivar share a similar strategy of achieving their political ambitions

September 20, 2017

Many religious organisations in Pakistan aspire to become vibrant sociopolitical movements, which can shape public views, influence policy discourses, and dominate the politics.

Indeed, almost all religious organisations follow a typical methodology of starting off as a social reform movement and gradually expand their infrastructure and ideological appeal to enter the mainstream political arena.

As this is a complex process, most of them fail in the way and settle into political or religious reform domain.

In the Indian subcontinent, only two movements have succeeded in achieving the objective. First was the Deoband movement, which, nurtured in Darul Uloom Deoband (1867), deeply influenced religious reformation, Muslim’s civil rights, and politics in the Indian subcontinent.

Initially the communal politics and later the creation of Pakistan changed the characteristics of the Deoband movement. At present, though, it has lost the character of a coherent sociopolitical movement, yet continues to influence academic, political and militant discourses in the country.

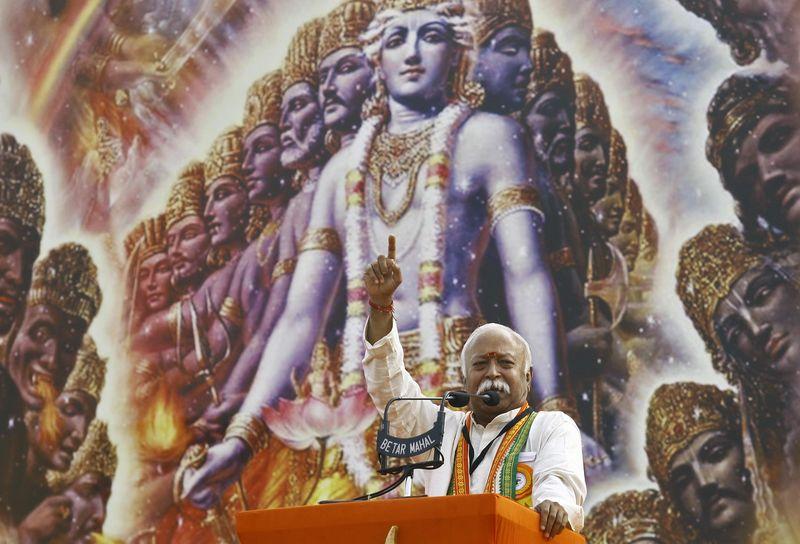

The second successful instance is that of the Sangh Parivar, a family of the ultra-nationalist Hindu organisations, which has gradually taken over the mainstream politics in India. This is a successful model and inspires many religious-ideological organisations in South Asia. In Pakistan, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) has evolved its structure on similar lines but Jamaat’s Islamisation vision was global and it borrowed the organisational structures from the leftist movements of the West.

However, Jamaatud Dawa (JuD) has the potential to provide a Pakistani version of Sangh Parivar. It seems the architects of the JuD have the Sangh Parivar model in their minds; the organisation is spreading its wings like the Sangh Parivar did in India. Despite having completely different sources of inspiration, Sangh Parivar and JuD share a similar strategy of achieving political ambitions through the religious-social mobilisation.

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a member of the Sangh family, wants to establish a Hindu state. The JuD also wants to establish a religious state. The Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) covers the social aspects of the RSS activities and mobilises the Hindu community for religious purposes. The JuD’s department of Da’awat-o-Islah (Preaching and Reform) does the same things.

The Bajrang Dal is the militant youth wing of the VHP and the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) is JuD's Bajrang Dal. Similarly, the RSS charity fronts, Sewa Bharati and Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), can be compared with Jud's Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation (FIF). Like the Sangh Parivar’s "Bhagat schools", in which children are provided a Sangh-sanctioned education, the JuD runs its own schools and madrassas. They are already in the media and entertainment business.

The JuD was missing a political party, which it has established with the name of Milli Muslim League (MML) in August this year; perhaps the MML could be conceived as Bhartia Junta Party of Pakistan?

The JuD’s organisational expansion is happening on the pattern of the ultra-nationalist Hindu parties. The Sangh Parivar parties are independent but part of a family, like LeT, JuD, FIF, and now MML deny links with each other but they still remain part of a larger family. The JuD has become a source of ideological inspiration, an elders' council that shapes narratives and provides policy guideline to member parties, like RSS in Sangh Parivar. The JuD has one disadvantage that the religious sect it represents is not the majority belief in Pakistan, which makes its expansion process very slow.

Some analysts compare JuD with Jamaat-e-Islami. Though the top leadership of JuD came from JI’s organisational tiers, their organisational evolution is different. As cited earlier, JI was mainly inspired by the leftist movements' organizational structures. At the same time, it has a close association with the Islamist organisations especially with Jamaatul Ikhwan (Muslim Brotherhood) of Egypt.

At one level, the development of the JuD can be compared with Hizb al Nour, a Salafi party of Egypt. The Hizb al Nour emerged as an alternative to Ikhwan in Egypt and in Pakistan JuD is capturing the political space of JI, as the strength of both parties lies in the urban areas of Punjab and Sindh.

Both Hizb al Nour and JuD had their respective establishments' patronage.

However, while the former emerged as a political partner of the Egyptian military regime, the latter served largely as a strategic partner of the Pakistani security establishment, though it is trying to find political relevance as well.

That could also be alluded to a different political culture in Pakistan as one can find a range of political parties with varying points of view, which was not the case in Egypt. The establishment here needed only a partner for strategic purposes. A major difference between Hizb and JuD is related to their worldviews. The Hizb in Egypt is considered a pragmatic and flexible Salafi organisation, but JuD wants to advance in politics with its radical worldview and militant credentials.

The JuD has essentially South Asian characteristics and is apparently following the local, or South Asian patterns, of expansion. But it is still struggling to balance between its ideological vision, which is global, and the political ambitions, which are local. This point makes it different from Sangh Pariwar and brings it closer to JI, which is facing the same dilemma.

Amir Rana is a security and political analyst and the director of the Islamabad-based Pak Institute for Peace Studies.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News or the Jang Group.