What happens to the MQM-P now?

Can the MQM-P rebuild itself from the ground up?

June 11, 2019

Inside a three-storey building in Bahadurabad, an upper-middle-class neighbourhood in Karachi, there is a flurry of activities. Footfalls can be heard up and down the staircase. Workers are pouring in and out of rectangular rooms, engaged on their cell phones. It is a nondescript space, small and narrow, in comparison to the daunting structure that was the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan’s (MQM-P) headquarters at Nine Zero in Azizabad. But for now, this will have to do, as a makeshift arrangement to house its workforce.

These days, just like its office, the MQM-P is a shadow of its old self. Ever since its headquarters was sealed in 2016, other offices of the party were also shuttered across the city. With finances drying up, the MQM-P first began working out of the residence of a party leader, Dr Farooq Sattar, and some adjacent buildings in P.I.B Colony. Finally, they were handed over keys to the buildings in Bahadurabad, from where they operate now.

Much has been said and written about the MQM’s fall from grace.

In the 1980s, the political party’s juggernaut was in high gear. It would pull out a stunning victory, scooping up every constituency in the city. Their win was due to a mixture of genuine support amongst the Mohajirs, an Urdu-speaking ethnic community, a drum-tight party structure, and the occasional use of violence and fear.

Back then, the MQM didn’t need anyone to help it win elections, which is why it never needed to bargain its position in the political corridors. But that changed. In last year’s general polls, it suffered its worst seat count in Karachi, winning only four national assembly seats from Karachi out of a total of 21. Post the election, it had to form an electoral alliance with the winning Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) to stay relevant.

As for its militant wings, it has been dismantled and abandoned after a paramilitary operation in Karachi. In private conversations, MQM-P leaders admit that there is no space for violence in the city now.

“Our party is more flexible today,” said Syed Aminul Haque, an MQM-P spokesperson and a parliamentarian, “We are completely against violence. We are ready to work with anyone to resolve the issues of the province.”

That may be true. Last month, the MQM-P held an Iftar dinner at its office and invited an arch-rival, Afaq Ahmed, the head of his own faction of the Muhajir Qaumi Movement. The two factions sat together under one roof after 25 years. Ahmed splintered from the MQM in 1990, after which a turf war began between the two groups resulting in the killing of thousands of workers.

At the iftar dinner, leaders of the recently-formed Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP), another splinter of the MQM, and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), and the Awami National Party (ANP) were also in attendance.

Those who have been observing MQM’s politics since a while say that the MQM-P has reached a new understanding with the power corridors. This may be why it has been handed over its offices in Bahadurabad, Shah Faisal Colony, Orangi Town and Mehmoodabad. They are also hopeful to get back control of its large setup in Gulshan-e-Iqbal. “The MQM-P has asked authorities for possession of 18 of their properties,” an insider, privy to the development, told Geo.tv.

Once the offices are up and running, a new party slogan will be needed to shed its old skin. Previously, the political party was running remotely from London by a party chief who was often portrayed larger than life. MQM’s entire politics evolved around his personality.

“After disconnecting the party from London, we have worked hard to regain the confidence of our workers,” said an MQM-P leader, who asked not to be named. “We took this decision to safeguard the interests of the Mohajir community.”

But there is another problem. At the moment, the PPP, a Sindhi-majority party, runs the Sindh province. “That is a concern,” says a law enforcement official, who chose to remain anonymous, “The security of the city is very important. There are fears that a growing sense of disempowerment among the Mohajir community could once again lead to ethnic clashes between them and the Sindhis.” This may be why the MQM-P is looking to safeguard its space in Karachi.

Recently, in the wake of the PTI’s plans to divide the Punjab province, the MQM-P announced that it too will table a bill in the parliament to carve out a new province in Sindh on an administrative basis. The demand has irked the PPP and other Sindhi nationalist parties.

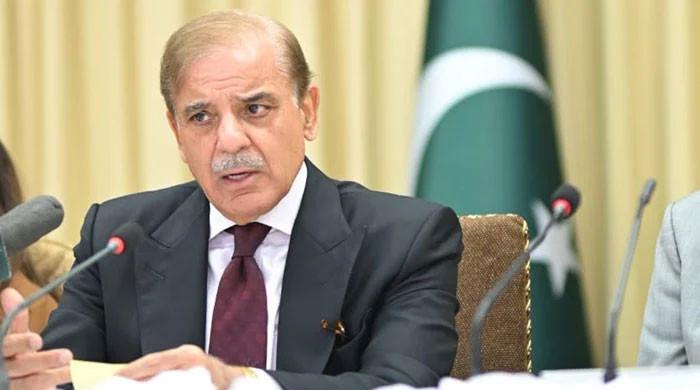

Separately, the prime minister has shot down any proposals of splitting Sindh. “There will be no need for another province after a new local bodies system is introduced,” he told a gathering in Karachi.

Still, the MQM-P is adamant to push ahead after the Eid holidays. “It’s up to the PTI to reject or support the bill, but if they choose to reject it, they will witness the consequences in the next elections,” said Aamir Khan, the party’s deputy convener.

So, what gives the MQM-P, a struggling political party, the confidence to pursue a defiant policy? Its recent successes, it says. “We won the by-polls in the local government polls, as well as the provincial constituency of PS-94,” sais Haque, “The mayor of Karachi is also from our party. We are still a political force of importance.”