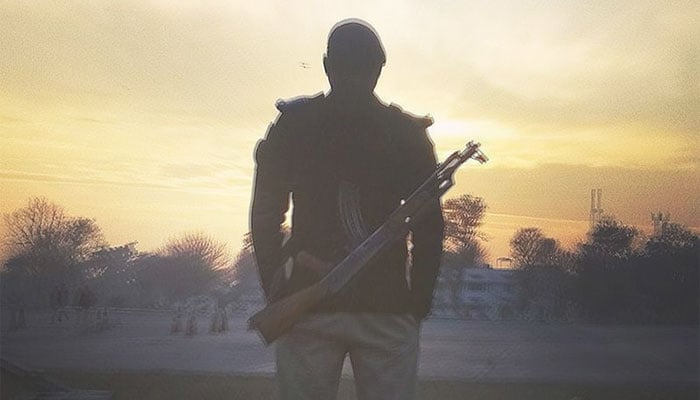

In Sindh's Kashmore district, police are helping the wrongfully accused

It is a dilemma of our society: once a suspect, always a suspect. Even if the person decides to give up the life of crime, the system continues to haunt them

October 11, 2019

Mola Dad Bugti’s life reminds me of a popular TV series, 'The Fugitive', which aired in the late 1960s. The American thriller told the story of a physician, who is wrongfully convicted for his wife’s murder. While on his way to the death row, he escapes. Thereon begins a manhunt, the doctor’s searches for the real killer, as the police search for him.

Bugti has a similar story. He fled his hometown in 1976, after being booked in a murder case by rival tribesmen. Life on the run was difficult, but he kept insisting he was innocent. Finally he surrendered. The case was disposed of, but the entire ordeal took 43 years to conclude.

Bugti was from the Kashmore district in Pakistan’s Sindh province. The district had for decades remained the hotbed for dacoits, terrorists and militants, which is why it reported higher rates of crime. Now under a new government scheme, the Surrender Justice Initiative (SJI), hundreds of proclaimed offenders and court absconders, even those who disappeared after seeking bail, are benefiting, ending the yearslong trauma for victims of tribal feuds.

As a result of the initiative, which is a joint effort by the local police and the judiciary, thousands of pending cases have been decided expeditiously. The man behind the SJI project is the Senior Superintendent of Police Kashmore, Asad Raza. The officer holds a master’s degree in public administration.

Mola Dad Bugti was one such beneficiary of Raza’s initiative. He was very young when the police booked him for killing rival tribesmen during a feud. Bugti first proclaimed his innocence and then, when he found no respite, he ran. But while he escaped, the family he left behind in Sindh were routinely victimized.

When Bugti first learned of the government scheme, he was uneasy about the idea. “I was scared,” he told the police, “that I might be killed in a police encounter instead.”

Kashmore has a population of 1.2 million and one seat in Pakistan’s parliament. Its notoriety is famous as it has one of the highest number of absconders and proclaimed offenders in the province. As per 2017 data compiled by the Sindh police, out of the 100,000 absconders in the province 45 per cent belong to the Larkana range, which includes Kashmore.

When officer Raza started the scheme, he was unsure of its success. But after running the idea by the lower and higher judiciary, he decided to go ahead with it. “In a tribal society rivals are booked, regardless of whether they committed the crime or not,” he told me over the phone, “I went through several such files and decided to ensure that justice should be done, especially in the cases of the absconders.”

The success of the scheme, he adds, can reduce tribal infighting in the area as well and eventually bring down crime.

ALSO READ: The life and death of a Bhutto

Post 2008, the paramilitary and police-led operation in Sindh to rid the province of militancy, had led to the creation of state-run rehabilitation centers. But a police officer, who asked not to be named revealed that when he was sent to crackdown on terrorism and dacoity, he found out that most of the “wanted” men were actually wrongfully accused of the crime and were scared to surrender.

There are cases pending in the courtrooms in Kashmore since the 1980s. Some of those who have recently been exonerated were booked in petty crimes dating as far back as the 1979.

Under the SJI system, the police provide legal cover and share expenses with the accused, who are not involved in heinous crimes, to help them get relief. The program provides a 50 per cent bail surety, with the help of the Local Citizen Committee.

Moreover, a separate cell has been created, staffed with junior police officers. They go through each person’s case file and send an application to the SSP. The SSP then personally interviews the people who want to surrender.

In another interesting case, a man was arrested in 1982. He escaped and went into hiding. Later, he had his death certificate sent to the police and the case was closed. The man then settled in Saudi Arabia. It was only until he lost his job that he was forced to return to Pakistan. When the man heard about the SJI initiative, his tribal elders went to meet Raza, who asked the man to surrender immediately.

These cases often remind me of the one I reported on in the 1980s. One such case was of a victim who was locked up in the central prison in Karachi for over 27 years. It took a while, but I finally dug out his case file, with the help of human rights activist, Ansar Burney, and the sessions court staff. When that man was finally released he tried to contact his family, but had no luck. Finally, he returned to Ansar Burney Welfare Trust. It was a truly tragic end to his ordeal.

The Inspector General police, Dr. Syed Kaleem Imam, has lauded Asad Raza’s efforts. He hopes that after taking the chief justice and the provincial government into confidence, the scheme can be extended to other parts of Sindh. This will be a welcome change as I can say with certainty that there must be thousands of other people, locked up or on the run, who are wrongfully accused, on the basis of enmity or rivalry.

It is a dilemma of our society: once a suspect, always a suspect, in the eyes of the police. Even if the person decides to give up the life of crime, the system continues to haunt him/her.

Asad Raza agrees, and promises that his police department is at least working to make life easier for those who want to return to normal life. “We have assured all those who are getting such relief that police would not create problems for them in the future,” he said.

Abbas is a senior columnist and analyst of GEO, The News and Jang. He tweet @MazharAbbasGEO