Blog: Deniers and a devil-may-care attitude during a pandemic

As our country confronts coronavirus crisis, there is need for all of us to start thinking about some hard and ethical questions

March 31, 2020

Everywhere, there are echoes of a deadly outbreak. But what is even more disturbing is the public response to it, thus far.

The coronavirus infection is growing exponentially in Pakistan, with over 1,800 cases diagnosed, at the time of publication. Still, many refuse to be careful, putting others at risk.

Charles E. Rosenberg, an American historian of medicine, argues that epidemics provide a sampling device for social analysis. As our country confronts this crisis, there is need for all of us to start thinking about some hard and ethical questions.

Why do so many people find it difficult to act in accordance with a minimal demand of morality, in wake of extremity? Are we collectively rejecting a reality? Are we trying to play down our moral responsibility in the wake of a national crisis? And would this outbreak force those ruling us to get their priorities right?

Related: Who to donate to during the coronavirus outbreak?

Denial appears to be our national coping mechanism to deal with a variety of circumstances and issues. Essentially if a situation is too much for us to handle, we tend to deny the existence of the problem. Eventually, the reality of circumstances kick in, and then we turn to blame or put the responsibility onto someone else.

Now, many denialists are poorly informed or unqualified to understand the reality of occurrences. While, some understand the reality and the relevant evidence but chose to discount it because they benefit from doing so.

However, most troubling are the denialists who are in position of power.

Keith Kahn-Harris, a famous sociologist and writer, recently said that “denialism is a mix of corrosive doubt and corrosive credulity”, because once you start mistrusting the established authorities of information, paradoxically you may be in danger of accepting the lie of others.

There is no doubt that denialism is dangerous and has become more prevalent, helped in part by social media. In the wake of outbreak, we opted for the same strategy of denial at least initially to give ourselves a false sense of security.

However, the media and civil societies have been guiding us all along regarding social distancing and the other protective measures needed to tackle the pandemic. Separately, the Sindh government took a lead in the battle against the coronavirus, and nudged us incrementally in the direction of more formalized set of restrictions. Yet, people were rushing to restaurants, the beach and parks.

What boggles my mind is that some of us, even today, are refusing to believe the reality of the moment and are rubbishing the pandemic as just a media hoax. It’s impossible to imagine what combo of circumstances may pull us back to reality. Stubborn religious clerics and pirs are adding to the confusion by pushing back against state’s measures to contain the virus. They are putting in jeopardy not only their own health and safety but that of their followers.

In the wake of the crisis, the consequences of a fragmented health care system becomes more visible. With one of the lowest public health expenditure in the world, as a percentage of the GDP, Pakistan lags behind many other nations in its health indicators.

Ill-equipped public hospitals lack the capacity to screen a large number of suspected cases. Nationally, there is legitimate concern that the nation’s supply of only one bed per 1,600 people cannot handle any big number of patients. The 1,700 ventilators across the country, for critically-ill coronavirus patients, may be insufficient to care for the people who would be unable to breathe on their own. Moreover there are only 220,829 registered doctors in Pakistan, for a population of over 207 million.

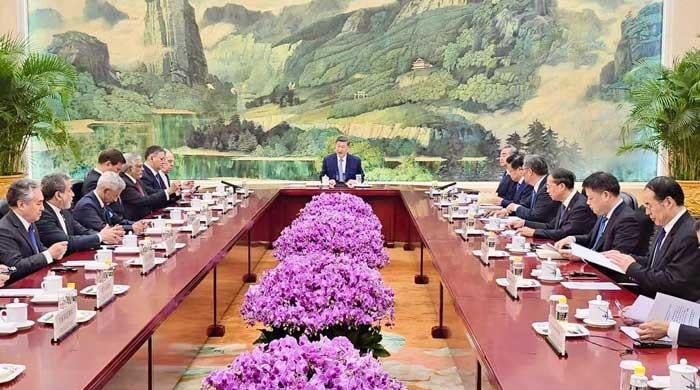

Fortunately, we have managed to get around 800 more ventilators with the help of China.

Poor governmental strategies coupled with the dearth of medicines, doctors and paramedical staff, means the country will struggle to cope with the outbreak if the number of cases were to spike. Even hospitals in the first world countries, with the best health care systems are overwhelmed.

It remains to be seen if this crisis, of this scale, can force the public and the government to rethink its priorities, in terms of healthcare and education. Or will the lessons learnt today be forgotten tomorrow.