The Single National Curriculum: A glitzy disaster

In Pakistan, most public schools are in dire need of investment, for the most basic of infrastructures, such as toilets, libraries and even laboratories.

August 11, 2020

Pakistan’s education system has two major problems. First, government-run schools have failed to deliver an education to young minds. Second, schooling at religious seminaries has remained unregulated for far too long.

The state’s newly unveiled Single National Curriculum (SNC) addresses neither of the two problems.

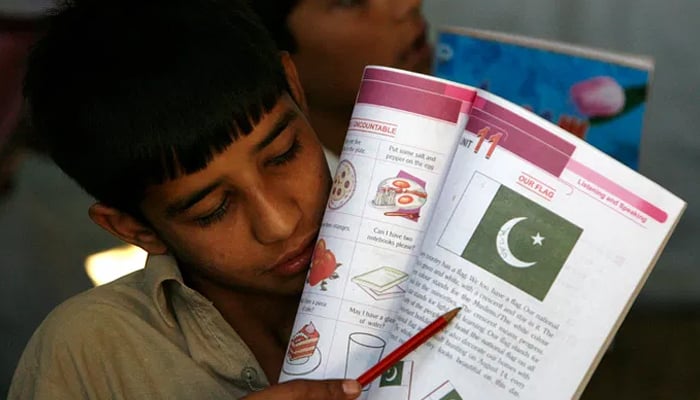

In Pakistan, most public schools are in dire need of investment, for the most basic of infrastructures, such as toilets, libraries and even laboratories. Then, there is the issue of out-of-school children. Pakistan’s student dropout percentage is 40 percent, at the primary level, one of the worst in the world.

Schools, private and public, are forced to recruit former students soon after graduation. Very few of whom have any preparedness to teach, and even fewer stick to teaching for long.

In contrast, madrassas provide free-of-cost education and with it, boarding, food and other facilities. But their students are ill-prepared for the job market.

With the new uniform curriculum the ruling party has made a commitment to both incorporate madrassas into the mainstream and to end the dichotomy in opportunities between public and private education.

However, those in power forget that a single curriculum has existed in the country since the 1970s, at least on paper, and the current one is very similar to that drafted in 2006 at the national level.

This SNC promises to bring uniformity. Now, even if the national curriculum is implemented, madrassas and private schools will continue to teach the syllabus they have already outlined for their students. Expect no changes there. Hence, the SNC will be an addition, not a replacement, increasing burden on young students.

How does the new curriculum plan to increase the number of children going to school? There is no clarity on that.

Another SNC claim is to shift school education from rote-learning to building an understanding. But to improve a classroom’s experience, the government will need to invest more in teacher education. Again, how and when will this happen?

Rather than spending an inordinate amount of time on drafting a lengthy document, which has become embroiled in controversy of late, the government can instead invest in printing more engaging textbooks, and improve the condition of existing public schools.

But that may not make for an attractive election slogan.

Mirza teaches sociology and politics in Lahore