One nation: Thinking beyond the Single National Curriculum

A single curriculum will not give all children same benefits, with elite schools continuing to offer far better facilities

October 21, 2021

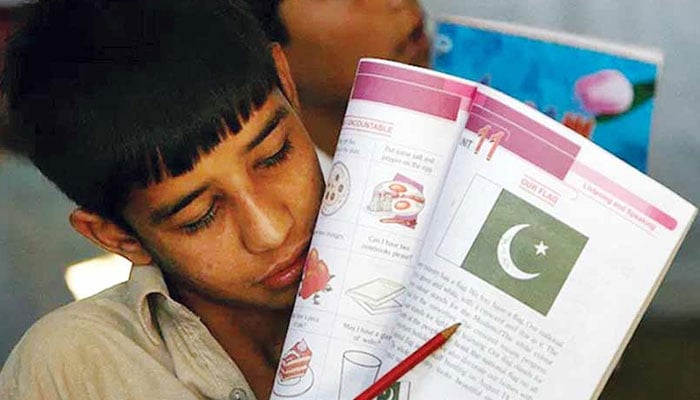

There has recently been a great deal of attention given to the Single National Curriculum (SNC) put in place by the PTI government. The purpose of the curriculum is to end the divide between elite private schools and low-tier public and private schools by ensuring they all study the same basic curriculum, even if schools are free to add to this.

The SNC has been debated widely. Questions have been raised about whether it is practical, who it caters to, given the content of the new books which are to be introduced, and the pedagogy incorporated within it, which some experts say simply does not meet the standards of teaching which should be available to young children. The SNC, already a cause of controversy across the nation, is initially intended for Grades I to V.

But beyond education, there are so many ways in which the nation is divided that we need to consider how we can, in the first place, create the one nation, one people, system in the country – rather than many tiers of people who live totally different lives under diverse circumstances. This, after all, is as important as offering them the same curriculum.

A single curriculum will not give all children the same benefits, with elite schools continuing to offer far better facilities and a far wider learning experience. The differences do not end here. We have seen in the crucial health sector how economic disparities affect so many people. We saw this during the last two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, and we also see it almost all the time and in all capacities. Government hospitals, which mostly cater to the poor, cannot offer expensive services that the rich can easily afford. Private hospitals, which charge huge amounts of money, are often of international standards and able to offer services mostly available in Western countries. The country has made no attempt to correct this system and spends a miniscule amount of the GDP on health, well below the levels recommended by the WHO and well below what would be a humanitarian norm in most countries.

This is the reason why on one of the many health indexes created by various organisations, Pakistan ranks dismally low and mostly below India. A number of surveys suggest that in South Asia, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal perform better than Pakistan in healthcare, and so do countries like Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, and other nations which are seen as the world’s poorer countries.

It is quite obvious that they care more for their people than we can and are more committed to offering all people at least some degree of equality in basic healthcare. On such lists, almost inevitably, European nations, notably Scandinavian states, and also an impressive number of countries in the Far East including Taiwan and Singapore, stand at the top. Malaysia also manages to get an impressive score, perhaps because it derives some benefits from its proximity to Singapore and a desire to emulate the country’s excellent healthcare system.

We also have examples such as those from Cuba which has no private hospitals and clinics and private doctors, but a wide training programme for doctors and an excellent public sector healthcare system which caters to all its people and offers them high-quality care. Even though Cuba has struggled to maintain its public sector systems since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990, losing the support it obtained from this bloc, it has essentially maintained much of its healthcare services, conducting home visits, especially for the elderly, looking into basic health problems, and attempting to prevent major issues before they arrive.

Indeed, the Cuban healthcare system has been rated so highly by some specialists around the world that patients have been advised to visit that country if they cannot afford high-cost healthcare offered in other top-ranking countries. It is also hardly surprising that the US usually ranks lower than European countries including the UK. It can be said that the superpower does not see people and their healthcare needs as a priority.

Pakistan needs to recognise that healthcare is a huge concern for people. Whenever a person falls ill, his/her family struggles to raise the amount needed for care and the provision of medications and support required after the crisis is over. There is simply no support for them and no means to obtain quality care. In rural areas and more remote parts of the country, the situation is even worse. There are some charitable hospitals in those areas which offer a better quality of care and some means for the poor to access high-quality medical practitioners.

This is true not only in the case of hospitals, and in events when an acute crisis occurs, sometimes pushing families who have so far managed to remain financially stable below the poverty line, but also in terms of day-to-day healthcare. Too many doctors, including those practising at some of the largest hospitals in the country, routinely prescribe a range of unnecessary antibiotics to patients, despite experts’ warnings that the overuse of antibiotics has led Pakistan into a situation where it is the target of multidrug resistant (MDR) tuberculosis and typhoid. The problem is now so acute that inoculations for children against MDR typhoid are being recommended in many parts of the country.

There are also other kinds of malpractices. Doctors themselves are often under pressure to cater to patients’ demands that they be made better as quickly as possible. The recognition that antibiotics will not help a viral illness is simply not there; also, self-medication is a norm with many people swallowing an alarmingly considerable number of antibiotics at the first signs of sniffles or a sore throat. In the long run, this is counterproductive and damaging to the health of a nation where resistance to antibiotics is growing quickly.

The lack of regulation of private hospitals and the overall private medical culture add to the problems. If we are to offer people an equitable or somewhat equitable system of healthcare, we need to look at China, Cuba, Turkey, Malaysia and other nations, which have achieved this in a far more satisfactory manner.

We also need to see why other South Asian nations stand well above us and what we can do to at least catch up with these countries and reform our healthcare system. We have to ensure that our healthcare sector serves people better, and by doing so, we can build a nation which is able to see itself as a single unit – rather than a divided country made up of people who live in extremely different conditions.

The writer is a freelance columnist and former newspaper editor and can be reached on [email protected]

Originally published in The News