What should be Pakistan’s economic growth roadmap?

95% of Pakistan’s growth is consumption-led, resulting in low savings and a low investment-to-GDP ratio

May 31, 2022

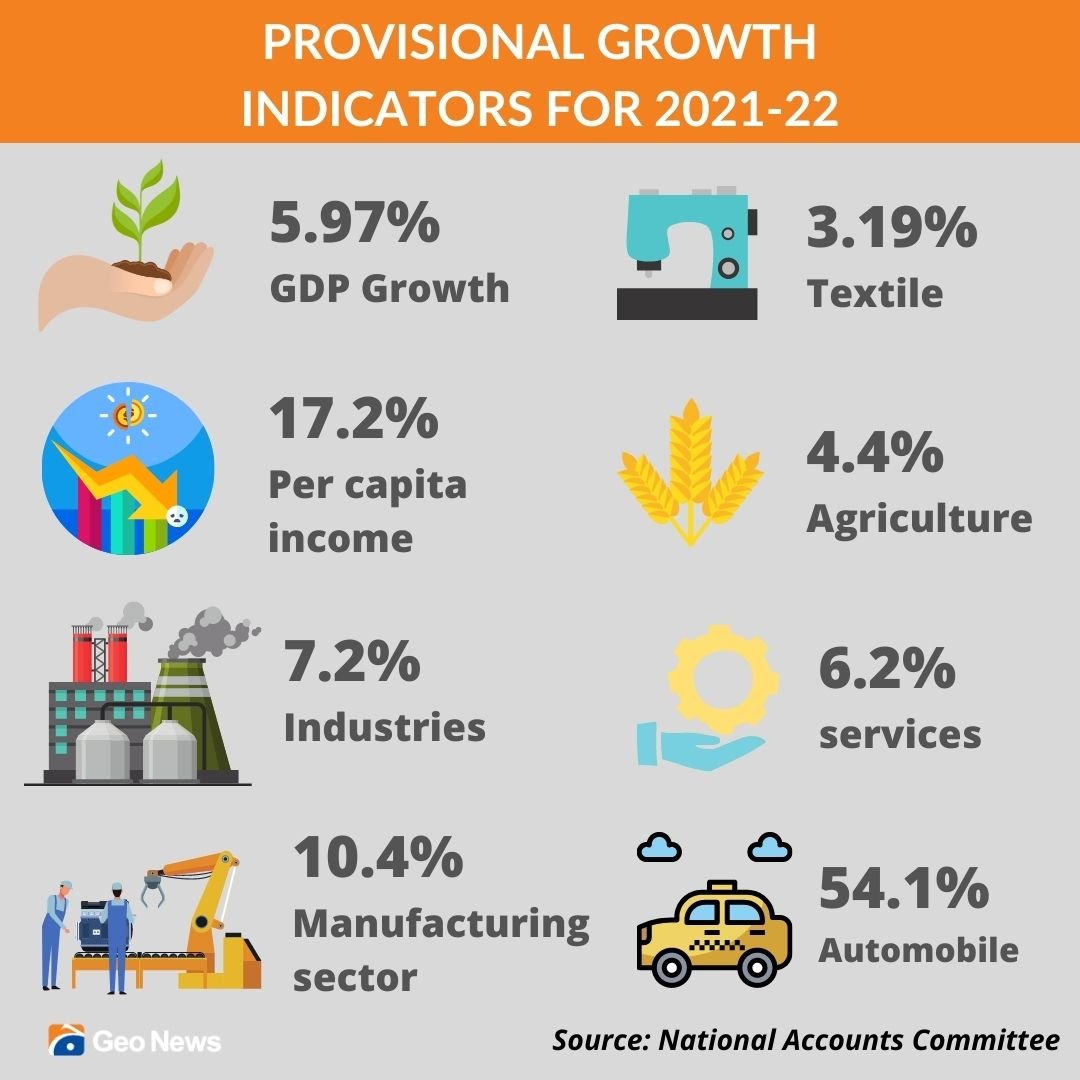

The good news is that, as per the national accounts committee’s numbers, the provisional GDP growth rate for the current fiscal year (2021-22) is 5.97%. The bad news is that, despite this healthy growth, Pakistan is once again facing the menace of twin deficits — dollars deficit (current account deficit) and rupee deficit (fiscal deficit).

This is not the first time that Pakistan finds itself in an economic mess despite healthy growth. One may argue that economic growth (an increase of per capita income) of five-plus percentage points for 2-3 consecutive years ends up overheating Pakistan’s economy. Such overheating turns its current account deficit unsustainable, resulting in a boom and bust cycle.

To set the context right, we should remember that 95% of Pakistan’s growth is consumption-led, resulting in low savings and a low investment-to-GDP ratio. Eighty-six per cent of consumption comes from households, making them highly vulnerable to any shock or reduced supply of resources. And finally, more than 90% of Pakistan’s growth is imports based, increasing its current account deficit.

Read more: The political and economic parallels between Pakistan and Sri Lanka

The above partly explains the context of the economic turmoil we face today. For the last two months, we have seen a blame game on the economic situation in Pakistan. The current government criticises the PTI government for providing ‘unfunded’ subsidies on fuel, and the PTI decries incumbents’ indecisiveness and economic mismanagement. This argument leads to inaction, which does not help curtail the current account deficit.

An increase in the current account deficit requires export earnings, increased remittances, foreign investment, or loans to bridge the dollar gap. Our exports and remittances are already at a record high. We don’t seem to be an investment hub, at least in the near future, primarily due to geostrategic reasons and our inherent flaws. Hence external financing is the only pragmatic solution in the short run to avoid the current account deficit.

However, this financing does not come through without a seal of comfort from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) estimates that from now till June 30, 2023, Pakistan’s external financing requirement (on top of export earnings and remittances) would be around $46 billion. The SBP anticipates that if the IMF programme gets resumed and Pakistan stays disciplined in it, it can fetch external financing of around $51 billion during the next 13 months.

Political uncertainty and the government’s reluctance to take ‘prior actions’ (especially revoking the blanket subsidy on fuel) were major bottlenecks in Pakistan’s IMF programme resumption. The previous government was also reluctant to go to the IMF for a whole year.

Read more: SBP autonomy is need of hour not just an IMF demand

However, it managed external financing from friendly countries like Saudi Arabia and China as a stop-gap arrangement. The incumbent government also tried the same, but friendly countries linked a rollover of their deposits in the SBP to the resumption of the IMF programme.

Mindful of the fact that it was not possible to economically sustain without IMF’s support, the government eventually decided to increase the prices of the POL, albeit in a staggered manner. A hike in electricity and gas tariffs and a further increase in the price of POL would follow in the coming weeks.

Part of the ‘prior actions’ for returning to the IMF’s programme includes steps such as policy actions in the federal budget for the next fiscal year for fiscal consolidation, remaining within a primary fiscal deficit threshold, collecting seven-plus trillion rupees revenue (more taxes), resisting the temptation for a spending spree in the run-up to elections, and further tightening monetary policy.

For a government entering into election mode a few months down the road, it is not easy to make unpopular decisions. Fortunately, the IMF gives a cushion to provide targeted subsidies.

Read more: The three challenges to Pakistan’s economy

Availing of this cushion, the government has announced to pay 14 million households a lump sum of Rs2000 per month. This one-off payment aims to reduce the impact of oil price hikes on low and low-middle income earners. This subsidy would be disbursed through the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), which uses a proxy mean test (PMT) to assess households’ eligibility for social safety-net benefits.

The higher the PMT of a household, the more well-off it is considered. The eight million existing BISP beneficiaries have a PMT of less than 30. For petrol-related payments, that threshold is increased to 37, covering an additional six million households with an average monthly income below Rs35,000.

Compared to the previous government’s subsidy on petrol and diesel, which cost four times more (Rs113 billion) just in the month of April, the current government’s subsidy of Rs28 billion looks pretty nominal. This is so, not because the amount allocated is too little or the targeting criteria do not cover the middle class who would feel the maximum brunt of inflated energy prices.

But because energy is not the only commodity that has gone expensive. The impact of the ‘triple C’ crisis (COVID-19, conflict in Ukraine, and climate change) on prices of food and energy in Pakistan has increased manifold due to the depreciation of the rupee and the inherent flaw in the quality of our economic growth.

Read more: Demystifying Pakistan's economy and the way forward

The UN has warned of an ‘unprecedented global food shortage, famine, destabilization of nations, and migration that could last for years. To meet any shortfall in local production, Pakistan used to import wheat from Ukraine or Russia.

The wheat from Ukraine has become inaccessible and from Russia untouchable. Hence, there is not only a shortage of supply of wheat in the international market, but it has also become expensive (63 per cent increase in price during the last five months).

This would turn our three million tons of imports expensive, raising the flour price in the domestic market. Low domestic prices of local produce add more incentive for wheat and wheat flour smugglers. The government needs to be mindful of it to keep the wheat flour prices stable.

Likewise, the prices of edible oil and fertilisers have increased manifold in the global markets due to the Ukraine war (Ukraine and Russia supply 75 per cent of the sunflower oil globally, and Russia is the largest exporter of phosphate and potash fertilisers worldwide). Imports of these commodities will pinch Pakistani consumers and the government for the next couple of years.

Read more: Budget 2022-23 dictionary — one-stop guide for financial terms

In the abovementioned context, taking fiscal consolidation measures (tough economic decisions) and winning back the trust of the IMF are important for our macroeconomic stability.

The IMF will remain relevant for us until our economic growth remains import-led and consumption-based. Unfortunately, we don’t have economic narratives of political parties. We have economic narratives of government and opposition.

The parties in opposition come up with the same narrative against the government that the parties in government had when they were in opposition and vice-versa. To improve the quality and composition of our economic growth, this game of musical chairs of economic narratives must end as it leads to a lose-lose situation.

In the short term, a win-win situation can emerge from the current situation if all political parties (irrespective of whether they are in government or opposition) support the tough economic decisions taken by this government (or provide practical alternatives to those decisions). Any party confident of making government after the next elections should contribute to achieving macroeconomic stability today, as it would be the biggest beneficiary of such stability.

Read more: Excessive macroeconomic imbalances may flatten growth in Pakistan, warns finance ministry

In the medium term, all political parties should start preparing an economic growth roadmap, to be part of their manifestos, which they will be pursuing to skip the boom and bust cycle.

The writer heads the Sustainable Development Policy Institute and tweets @abidsuleri.

Originally published in The News