What do the audio leaks tell us?

Someone may ask both Mr Leghari and Mr Jhagra: in what capacity is Tarin issuing orders to elected members of parliament, and vital members of the cabinet in both provinces, writes Mosharraf Zaidi

August 30, 2022

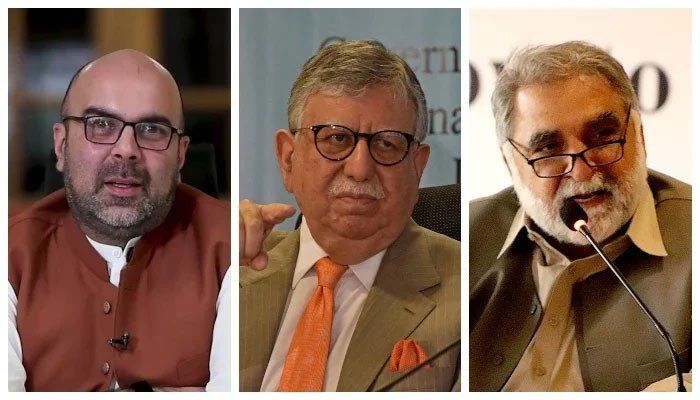

I have just heard the leaked audio of conversations, allegedly between Shaukat Tarin and the two finance ministers in PTI-run provinces – Mohsin Leghari in Punjab, and Taimur Khan Jhagra in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. One is lost for publishable words. But here goes.

Tarin’s tone and tenor during the two conversations is not that of a minion, hesitatingly following party orders. He is very much a commanding force in the conversations. Someone may ask both Mr Leghari and Mr Jhagra: in what capacity is Tarin issuing orders to elected members of parliament, and vital members of the cabinet in both provinces. Where was Chief Minister Mahmood Khan during this conversation? Where was Chief Minister Pervez Elahi? Of course, we know the answer to this: Tarin is the voice of Imran Khan.

There is certainly some betrayal of the laws of basic macroeconomics in these conversations. More serious and severe is the betrayal of this country’s flood ravaged people. In what universe can the sabotage of a vital IMF programme tranche release be deemed in the public interest, especially as 30 million people watch their homes, livestock, schools and basic health units drowning in record monsoon rains?

Suffice it to say, the upper limit for excusing Imran Khan’s singular obsession with securing power in Pakistan has been breached many times. Should there be any negotiating or cutting of slack for a political cult that sees its leader as the only pathway for a secure and prosperous country? Can there be a reconciliation with such sentiment? Would it not be naive to continue to afford the PTI cult the veneer of decency that it has secured through its now hugely popular appeal? Let’s pause and remember: the PTI is likely the most popular party in the country, and Imran Khan is clearly the most popular leader in Pakistan. But there is no law that dictates a paralysis of all norms to cater to what feels good – no matter how many people are under the influence.

Scorched earth politics is exactly that: it scorches the earth and leaves nothing alive. The PTI isn’t just providing its opponents with ammunition to denigrate its core purpose in public life (which seems to be not much more than catering to Imran Khan’s whims). It is also setting a precedent. If and when the PTI comes back into power, it will likely face provincial governments that are not PTI-led, behaving exactly in the way Tarin has sought to direct Punjab and KP to behave. What will the great Kaptaan do then? He doesn’t care. But we should.

Of course, the Kaptaan’s popularity – even when exposed for being what he is – comes from successive failures of traditional political and military elites to protect Pakistanis from catastrophes large and small. The latest of these are this monsoon season’s catastrophic floods – already almost certain to be worse than any in my lifetime. The damage from these floods is historic, with estimates of the number of Pakistani affected exceeding 30 million, it is almost certain to surpass the 2010 floods which affected over 20 million Pakistanis, and which was estimated to have done over $10 billion in damage.

Images of the helplessness of ordinary Pakistanis and the ferocity of extraordinary flood water may feel like too much to bear. Our capacity to process grief and sadness surely has limits, but is there a limit to the suffering of Pakistanis living on the edge in places like Swat, Dera Ghazi Khan, Qambar Shahdadkot, and Jhal Magsi?

In Balochistan, 31 out of 35 districts are now a ‘Calamity Hit Notified District’. In Sindh, 23 out of 30 districts are similarly notified. In total, there are 72 districts across the country that have been classified as such.

Pakistani governance’s dirty secret is that ‘The District’ is the country. It is where the rubber hits the road for everything macro. Islamabad (the seat of the federal government), Rawalpindi (the seat of power), and whichever of the relevant provincial capitals we may be dealing with at any point in time – all depend on the capacity of the district administration to do whatever is required to sustain the ‘governance model’ in this medieval tribal collective of a wannabe republic. Ordinarily, there are two things Pakistan’s elite want in ‘The District’: the maintenance of law and order and the extraction of revenue.

Provinces themselves are outsiders in the most important conversations about the people of the country, so whatever power they have is residual to what they would like. This means that they have no incentive to concede power. This is reflected both in the ongoing four-year-old KP-federal dispute over funding for the newly merged districts, as it is in the conversation between Tarin and Jhagra. What does this mean for the ‘The District’ – the highest level of local governance in the country’s administrative, fiscal and political systems? The short answer is a lack of administrative, fiscal and political space. The District, therefore, is where Pakistani governance goes to die. And remember: the district is the country.

To understand the impact of the floods on Balochistan and Sindh, we need to understand the nature of administrative, fiscal and political space in those provinces – and more importantly in the 54 Calamity Hit Notified Districts in those two provinces.

Balochistan didn’t always have 35 districts. The most recently notified district is Chaman, borne of the asexual reproduction of districts that provincial governments have resorted to as a purported instrument of better management of the diversity and vastness of the country. Twenty years ago, there were 26 districts in Balochistan.

Sindh lags on most human development and infrastructure indicators, but it rarely gets left behind on matters like this. Like Balochistan, the Sindh government has proliferated districts like rabbits. Nine new districts since 2004 in Sindh too.

So how is it that despite the inflation in the number of districts, there doesn’t seem to be any substantial improvement in the degree of vulnerability of Pakistanis living in these areas?

Let’s first dispense with the nonsense. The answer to everything is not ‘corruption’. In fact, corruption is rarely the primary answer to anything. It is a convenient catch-all, emotive basket into which Pakistanis have been serenaded into dumping all complex normative, institutional, structural, fiscal and political issues to explain the shortcomings of the country.

Let’s also be clear: the effort and will of the average Pakistani civil servant and public employee, especially during a crisis (earthquakes, floods, war), is otherworldly. Rare, if ever, does a country have the kind of the stock of sacrificial lambs as Pakistan. District, provincial and national level officers, beat policemen and policewomen, soldiers, spies and contractors – no matter what vertical, the Pakistani public servant seems endowed with superhuman capacity to put her or his life at risk in the line of duty. This is all very admirable but should not be a feature of any country’s public sector. The fact that the opportunity for such heroism is available should be central to the diagnosis of what is broken in the country.

Finally, it is important to note that despite the howling protests of many experts, the cupboard is not exactly bare as far as disaster management, and climate change legislation and policy in the country. Pakistan has plenty of both, and has had it for a long time. Disaster management and climate change both have laws, ministries, departments and substantial budgets in Islamabad. Some measure of similar capital stock exists in the provinces too. Where does it not exist? That same place where Pakistani governance goes to die: The District.

Of course, on paper, every district has a district disaster management authority. These are headed by the same one-window operation that is the one-window for all things at The District: the district administration.

The Imran Khan versus everybody else fight will not stop for the floods. Kaptaan is too important to let such tragedy get in the way of his crusade. But Pakistanis need to be able to look beyond the sophistry of a magical populist leader. The country’s structures are designed to keep proliferating useless districts; keep consuming the efforts and lives of hardworking civil servants, cops and soldiers; keep consuming your tax money and international assistance; and continue to tragically watch poor people drown on scorched earth.

The writer is an analyst and commentator.

Originally published in The News