Karachi's roads are killing us

Every year, thousands of people die or become disabled due to road traffic injuries in the megacity of Karachi

May 21, 2025

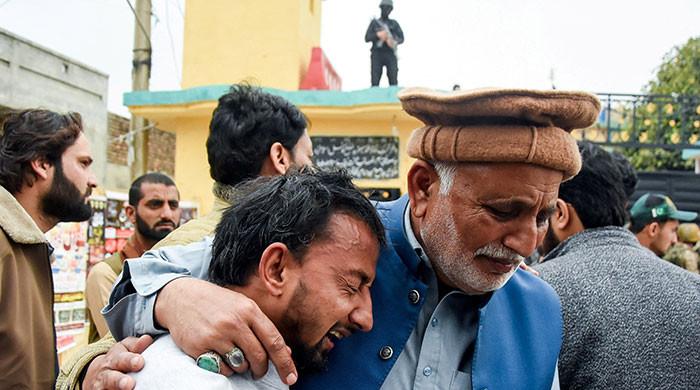

On a Monday evening in Ramadan, just moments before iftar, Abdul Qayyum, 25, was taking his pregnant wife, Zainab, for a routine check-up. As they waited at the junction of Malir Halt and Sharea Faisal, a speeding water tanker tore through their lives. In the face of unimaginable pain, Zainab gave birth to their child — an innocent life brought into this world, only to be lost moments later.

Every year, thousands of people die or become disabled due to road traffic injuries in the megacity of Karachi. Manoeuvring the streets of Karachi is a deadly gamble, and Abdul Qayyum's young family paid the price with their lives. This is a largely preventable public health crisis, a moral failure that demands our attention.

We are living through the Decade of Action for Road Safety (2021–2030), as declared by the United Nations. The goal is to halve road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030. But for Pakistan — and cities like Karachi — to meet this goal, we must stop treating road safety as an afterthought.

A national epidemic of negligence: Road traffic crashes are a leading cause of death globally, claiming nearly 1.3 million lives each year and injuring 50 million more.

Alarmingly, road injuries are the leading cause of death for children and young adults aged five to 29, and over 90% occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).

In cities like Karachi, the burden of this crisis falls heavily on the poor and vulnerable – those who rely on two-wheelers or informal public transport or who must walk through unsafe, chaotic roads every day. These communities are not only at risk of death or disability but are also plunged into cycles of poverty when a family's breadwinner is lost to a preventable crash.

The strain on Pakistan's health system and the need for EMS reforms: Pakistan's healthcare system is overwhelmed by road traffic injuries (RTIs), with emergency departments, particularly in Karachi, flooded by victims requiring expensive, long-term rehabilitation. High out-of-pocket costs and limited insurance push families into poverty.

Road crashes are largely preventable. A key issue is the inadequate post-crash response; while emergency medical services (EMS) have improved, further investment and regulatory support are needed. Although 1122 is a positive step and serves as a central emergency response number, its reach and accessibility vary across provinces.

The trauma care network is poorly coordinated, with significant gaps in services, including insufficient medical resources, under-equipped ambulances, and disorganised pre-hospital and hospital-based care.

As a result, victims often die before reaching an appropriate health facility or within hours of arrival at the hospital. Pakistan also faces a severe shortage of trauma-trained healthcare professionals, with only one female trauma surgeon in the country as of 2024.

Limited data, low research funding, and a lack of public health involvement hinder road traffic injury (RTI) prevention. RTIs are often viewed as a transport issue rather than a public health priority – a mindset that must change to curb rising accidents and save lives.

To strengthen trauma care in Pakistan, the AKU Centre of Excellence for Trauma and Emergencies (AKU-CETE) is leading a multi-hospital trauma registry. Collecting data from four hospitals, the registry reveals that more than half (59%) of 8,395 cases are due to road traffic crashes. The registry tracks mortality and disability outcomes to help identify care gaps and guide lifesaving improvements.

Making helmets affordable and enforcing seatbelt use: Head trauma is the leading cause of death for motorcycle riders. Safe, quality helmets reduce the risk of death by over six times and brain injury by up to 74%. However, despite these benefits, helmet use remains low in many LMICs, even as motorcycle numbers rise.

A national campaign should promote affordable, quality helmets through partnerships with local manufacturers, offering subsidised rates and distribution at major transit points. Mass awareness campaigns can further educate the public, while tax breaks for helmet manufacturers could help. Enforcing seat belt laws would also significantly improve road safety.

Turning bystanders into lifesavers through training: In the critical moments following a road traffic accident, bystanders often find themselves overwhelmed or distracted, capturing the chaos on their phones instead of offering life-saving help.

The lack of knowledge about how to respond in such situations is a systemic failure that must be addressed. For survival, the first link in the chain of survival — the bystander's ability to act — needs to be strengthened through proper training.

Citizens must know which emergency numbers to call and what information to provide to ambulance services. Bystanders should also be trained to control bleeding and stabilise victims while waiting for help.

A major barrier to bystander intervention is the fear of legal repercussions. Many potential lifesavers hesitate to act because they fear being held liable if something goes wrong. Pakistan also urgently needs Good Samaritan laws that protect and encourage bystanders to help without fear of legal repercussions. No one should be punished or harassed for trying to save a life.

When ambulances are delayed, bystanders often panic and transport victims themselves, sometimes in motorcycles or rickshaws, which increases the risk of further injury. In their haste, they overlook the most crucial step – controlling bleeding.

Focusing on stopping the bleeding first, rather than rushing to the hospital, is essential to improving survival chances. Properly addressing these needs through well-structured, national-level training programmes can significantly reduce long-term disabilities and fatalities.

Initiatives like the Pakistan Life Savers Programme are making a real impact by training ordinary people — traffic police, law enforcement and citizens — in bleeding control and life-saving techniques. Over 400,000 Pakistanis have been trained so far, which continues to rise.

But this cannot remain the work of a few – it must become a national mandate because in the critical minutes before an ambulance arrives, a trained bystander can be the difference between life and death.

We cannot allow more lives to be lost to a broken system. It's time to act, decisively and urgently. This is not just a road safety issue. It's a health crisis. A human crisis. We need urgent investment in emergency medical services, nationwide life-saving training programmes and a stronger chain of survival – from the street to the hospital.

Let's build a system that saves, not one that delays.

The writer is an expert in emergency medicine and the director of the AKU Centre of Excellence for Trauma and Emergencies.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

Originally published in The News