Game theory at the border

In resisting, Islamabad wasn’t merely holding ground but rejecting diplomatic model that substituted coercion for consensus

May 24, 2025

From my Boston apartment — laptop open, law-school finals looming — I scrolled a torrent of claims: Karachi’s port in flames, Lahore under siege, Islamabad reduced to rubble. Indian channels reported victory with breathless certainty. Even the Indus Waters Treaty, they boasted, had been suspended. Celebration drowned out legality.

But beyond the euphoric headlines, reality unfolded quite differently — and far more swiftly. Within days, New Delhi’s military initiative stalled, its tactical gains proving both limited and unsustainable. Pakistan’s defensive posture, contrary to the anticipated collapse, held firm.

Rather than folding, Islamabad met the moment with unexpected cohesion and strategic discipline. Initial Indian incursions encountered stiff resistance, and the momentum quickly gave way to a grinding impasse.

Even India’s overreliance on its Rafale fleet, seen as a symbol of air dominance, proved misplaced. According to a CNN report citing French intelligence, at least one Indian Rafale jet was downed by Pakistani forces, marking the first known combat loss of the aircraft and casting doubt on the assumed air superiority advantage.

In a move that surprised even seasoned analysts, the conflict’s tempo shifted not in favour of the larger force, but toward a precarious equilibrium neither side had fully anticipated.

International reaction too shifted swiftly. Major powers, including the US, China and the Gulf bloc, issued measured but unmistakable calls for de-escalation, humanitarian restraint and a return to diplomatic channels. Behind the misfire lay a deeper misjudgment — one rooted not just in military calculus, but in flawed assumptions about escalation psychology and political will.

Why did India, a state with overwhelming military superiority and international clout, falter so quickly? The answer lies not in battlefield performance but in strategy. New Delhi approached the conflict as a coercive transaction — an attempt to impose new regional boundaries not through formal diplomacy, but through brute force framed as policy.

The goal was never total occupation or regime change; it was to compel Pakistan to accept a new normal under duress.

But this was not a war of necessity. It was a war of perception, calibrated to extract concessions by inflicting calibrated pain. India’s leadership wagered that overwhelming pressure, delivered quickly and decisively, would fracture the Pakistani state’s capacity to resist or retaliate.

But coercion carries its own risks, and game theory offers a sharp lens through which to view India’s miscalculation. As Nobel Laureate Robert Aumann observed, wars often function as rational bargains pursued under extreme incentives; the side that credibly threatens the higher price usually wins the concession.

Similarly, Thomas Schelling argued that the essence of power in conflict lies not in brute dominance but in the credibility of one’s threat.

India approached this war as a transactional negotiation by force, assuming that limited violence would extract political concessions without prolonged resistance. But Aumann’s theory of repeated games warns that adversaries rarely capitulate if today’s concession signals vulnerability tomorrow.

Pakistan understood that logic. Yielding would not have ended the pressure; it would have invited more. In resisting, Islamabad wasn’t merely holding ground but rejecting a diplomatic model that substituted coercion for consensus.

New Delhi underestimated that power without clarity of objective invites strategic ambiguity — and ambiguity breeds failure. There was no defined exit ramp, no credible theory of victory, and no coalition willing to underwrite India’s gamble.

Operation Sindoor collapsed under its own contradictions. Pakistan, sensing the absence of escalation control, refused to play by India’s timeline. By denying India a clean win, it transformed what was intended as a one-sided imposition into a contested space that soon bore diplomatic consequences New Delhi had not anticipated.

The effort to assert dominance had backfired, revealing that a state’s ability to act with force does not guarantee it can do so without consequence.

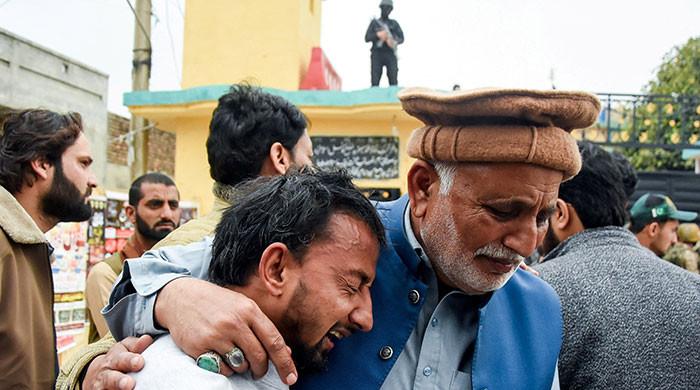

Still, as images of bombed-out buildings and disrupted lives flashed across South Asian screens, Indian media clung to an imagined triumph. Talk shows, op-eds and orchestrated military briefings sold a vision of success that diverged starkly from the diplomatic cables and internal assessments leaking out of global capitals.

Let’s not forget the piece de resistance: the supposed suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty — hailed as a stroke of nationalistic genius, yet legally untenable under its established provisions, potentially denying 240 million people access to water. In the end, these symbolic gestures did little to alter the war’s outcome, but a great deal to erode regional trust.

In hindsight, India’s mistake was not in using force but in misreading the strategic terrain. Power, especially in a nuclear region, is as much about restraint as reach.

The tools of coercion are sharp, but brittle. Once wielded without calibration, they lose their edge. Pakistan’s resistance was not heroic in mythic terms; it was strategic in political terms. It understood that surviving round one was the only way to prevent round two. The so-called ‘decisive strike’ became a case study in how imagined supremacy can unravel when tested against institutional will and geopolitical interdependence.

If there’s a lesson here for other regional powers — be they in East Asia, the Caucasus or Eastern Europe — it is this: transactional warfare often collapses under the weight of its own logic. States that gamble on quick coercion, hoping to reset regional realities without enduring political solutions, frequently misjudge the variable that matters most: the opponent’s will.

India’s 2025 gambit fits the same pattern: a hegemon, dazzled by its own strength, discovers too late that the adversary’s will is the decisive variable.

The lesson is stark. Power resides not merely in GDP rankings or aircraft inventories but in the capacity to price escalation credibly — and to read the opponent’s pricing just as well. Pakistan did both. India, believing in its own unassailable advantage, forgot that every conflict is a negotiation played under uncertainty. As game theory foretells, mispricing that uncertainty can turn a confident opening bid into a costly public defeat.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer is a lawyer.

Originally published in The News