What was the SCO summit about?

SCO is is becoming a forum where resources, politics, and strategy intersect just enough to shape outcomes

September 03, 2025

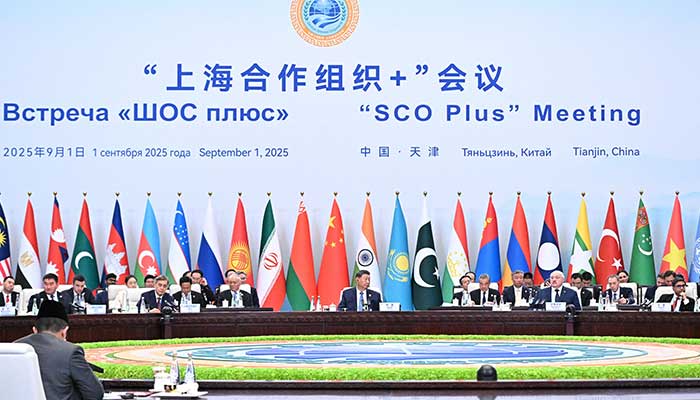

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation's summit in Beijing unfolded in a climate of heightened regional expectations.

What has long been viewed as a largely rhetorical platform for Eurasian cooperation is being steadily reshaped by Beijing and Moscow into something more developmentally oriented.

At the meeting, China's leadership announced steps to establish an SCO development bank and pledged a new line of credit and soft loans spread over the next three years.

The amount may not be impressive in global financial terms, but for member states facing economic distress, including Pakistan, the message was unmistakable: this forum will not only discuss security and multipolarity but also begin to channel funds and investment into tangible projects.

For Islamabad, that promise comes at a moment when breathing space is scarce, and every dollar counts.

The summit was also notable for the contrast in tone between the addresses of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistan's Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

Modi, appearing in China for the first time since the violent border standoff in Ladakh in 2020, stuck closely to the themes India has consistently raised in such gatherings. He spoke of terrorism as a universal menace, making it clear that states supporting violent networks would eventually face consequences.

He also repeated India’s reservations about cross-border infrastructure corridors that do not respect sovereignty, a veiled reference to the Belt and Road Initiative and specifically the CPEC alignment through Gilgit-Baltistan.

Modi used the occasion to highlight that India’s preferred model of regional connectivity lies in ventures like the Chabahar port project and the International North–South Transport Corridor, which, in Delhi's view, builds trust rather than infringes upon contested borders.

Shehbaz Sharif, on the other hand, echoed the language Beijing has made central to the SCO: respect for territorial integrity, mutual development and inclusive cooperation.

By carefully framing Pakistan's position around sovereignty while simultaneously leaning into the promise of deeper industrial, technological and agricultural cooperation, his speech aimed to neutralise India’s recurring critique and reframe Pakistan as an indispensable partner in the bloc's new economic chapter.

Beyond the plenary, Sharif's engagements in Tianjin and bilateral meetings reinforced the message that Islamabad wants to turn the second phase of CPEC into a story not merely of roads and power plants but of skills, factories and innovation.

It was a script designed to cast Pakistan not as a supplicant but as a willing participant in the SCO's evolution. Both leaders, in their own way, acknowledged the same reality: the SCO is drifting away from its early identity as a security platform and becoming a forum where development, connectivity and financial support take centre stage.

But they diverged sharply on what this should mean. India views the initiative as risky if it legitimises projects that trespass into disputed territory, and it insists that security threats like terrorism must remain the group’s central concern.

Pakistan, by contrast, views the new financing and project-based emphasis as an opportunity to alleviate its fiscal burdens, expand CPEC into sectors that generate exports and jobs, and gain legitimacy as a key corridor state.

For Islamabad, the week offered a rare convergence of opportunity. With Chinese backing, the SCO's proposed lending mechanisms could allow Pakistan to access alternatives beyond its exhausting cycle of IMF negotiations.

Even relatively small credit lines, if coupled with better governance, could jump-start long-promised special economic zones or fund modernisation in agriculture. The real challenge lies not in announcements but in delivery. To ensure that procurement is transparent, projects are not politicised and infrastructure actually produces productivity gains rather than white elephants.

Sharif’s government now faces the hard task of matching external pledges with internal reform.

India’s approach, in turn, was cautious but uncompromising. By restating its well-known position that connectivity cannot be imposed without consent and by again prioritising terrorism, Modi ensured that Delhi's record remained intact.

Yet the SCO's culture of consensus and its China-led orientation mean India’s sharpest concerns are often diluted in final communiques. Delhi risked appearing like a participant whose voice is registered but not amplified. Its answer has been to champion its own corridors – Chabahar and INSTC – but the credibility of these projects depends on cargo flows and timetables, not only summit speeches.

The International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a multimodal trade route (combining sea, rail and road) designed to connect India, Iran, Russia, Central Asia and Europe in a shorter, faster and more cost-effective manner than traditional maritime routes.

It was first conceived in 2000 through an agreement between India, Iran, and Russia, and later expanded to include more than a dozen member states, including Azerbaijan, Armenia, Kazakhstan and others.

Unless India can demonstrate that its preferred routes can deliver faster and cheaper access to Central Asia, the risk is that the SCO’s economic turn leaves Delhi more marginal than central. The politics around the summit were, as usual, fuelled by optics. Clips of leaders standing together, exchanging brief greetings or attending ceremonial events drew disproportionate attention.

Some Indian outlets celebrated images of Modi in conversation with Xi and Putin. Some Pakistani channels stressed Sharif’s presence alongside the Chinese president at commemorative events.

But the deeper story lay in the speeches and in the chair’s financial announcements. China reinforced its role as the primary architect of the SCO’s new phase, while Pakistan positioned itself as a beneficiary and partner in that design.

India maintained its principled reservations, ensuring it could not be accused of disengagement. What, then, might each country gain or lose from this shift? For Pakistan, the potential gain is twofold: fresh financial commitments that diversify its external options, and diplomatic cover in a bloc that amplifies its partnership with China.

The symbolism of being cast as central to SCO connectivity is valuable at a time when domestic pressures mount. For India, the risk is not immediate isolation but gradual erosion of influence.

Its insistence on sovereignty resonates at home and among some external partners, but within a forum where Beijing sets the tempo, Moscow provides backing and Central Asian states are eager for investment, India's objections can seem like background noise unless matched with viable alternatives.

Ultimately, the SCO in Beijing underlined that South Asia’s two rivals are playing different games on the same stage. Pakistan seeks capital, legitimacy and partnership through CPEC 2.0, while India insists on principle, sovereignty and caution in security. China, meanwhile, ensures that both arguments must be conducted in an arena it increasingly dominates.

The outcome of this contest will not be decided by summit speeches alone. For Pakistan, success depends on whether external pledges translate into functioning industrial zones, better-managed power systems and skills development. For India, it rests on whether its alternative corridors move from blueprint to functioning trade arteries.

The lesson for Pakistan is to welcome new finance but remain vigilant about the conditions, even when they are not spelt out as explicitly as those in IMF programmes.

Only when external support is tied to internal reform has Pakistan seen sustainable growth. The lesson for India is that repeating its red lines is insufficient; it must prove through real infrastructure and trade that its model of connectivity is more viable than Beijing's.

Both will have to do more than talk if they are to convert summit presence into a durable advantage. The SCO may not rival BRICS or replace Western financial institutions, but it has outgrown its reputation as a mere photo-op. It is becoming a forum where resources, politics, and strategy intersect just enough to shape outcomes.

Pakistan left Beijing with promises of money and the aura of partnership. India is left with a reiteration of principles that guard its red lines but do not shape the bloc’s trajectory.

In the shifting geometry of Eurasia, one neighbour appears to have gained a little room to manoeuvre, the other a reminder of its constraints. Both, however, still determine their altitude through the work they do at home.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer holds a PhD from the University of Birmingham, UK. He posts @NaazirMahmood and can be reached at:[email protected]

Originally published in The News